Context matters: Image and Text in the Works of Allan Sekula and Martha Rosler

by Karen Fromm

Under the title [IMAGEMATTERS], Karen Fromm, Sophia Greiff, Anna Stemmler and Malte Radtki have created a platform for discussion about issues in photographic practice, discourse in the theory of image and photography as well as in visual and cultural studies.

The essay presented here by Karen Fromm is part of the second [IMAGEMATTERS] publication image/con/text: Documentary Practices between Journalism, Art and Activism, which has been published in 2020. It follows on from an international symposium which was held at the Hanover University of Applied Sciences and Arts in autumn 2019.

The search for new narrative forms in the field of photojournalism and documentary photography – stretching perspectives beyond the conventional understanding of the documentary form – is the topic of numerous contemporary debates. The volume image/con/text. Documentary Practices between Journalism, Art and Activism delves further into the possibilities of the documentary and the development of visual narrations that subvert the traditional viewing habits, expectations and stereotyping of classical documentary photographic narrative forms. The contributions in image/con/text focus specifically on the textuality and contextuality of documentary practices and on explorations of their bounds, in particular the relationships between art, documentation and journalism. image/con/text examines image/text relations in notable contemporary and historical projects, focusing particularly on the medium of the photobook, but also encompassing film, multimedia and the comic genre. The strategies examined bring together journalistic, artistic and activist positions, weaving fact and fiction to reveal the constellations of power in the process of representation. The entire book can be accessed here.

The Photocaptionist is delighted to premiere the English translation of Karen Fromm’s essay here.

Context matters [1]: Image and Text in the Works of Allan Sekula and Martha Rosler [2]

A strong tendency to push beyond the purely visual narrative is apparent in contemporary works seeking innovation in documentary practice. Whether in the exhibition context or the medium of the photobook, a multitude of materials and textualities are employed. The overlapping discourses surrounding their application point to diverging objectives in the spectrum between open structures of meaning and contextual determination. On the one hand there is an interest in presenting the topic in a comprehensive and sophisticated form by combining various forms of imagery (which may be texts and documents as well as photographs), where the different discourses appear to expand and reinforce one another, striving above all for legibility. [3] Other works consciously present heterogeneous forms of representation in an incoherent and isolated form where temporal and spatial discrepancies and discontinuities are explicitly desired. Their combination emphasizes the indeterminacies resulting from the confrontation of the different descriptive systems. Within a single work they not only convey different perspectives on topics and issues, but also and at the same time open up a forum for mutually relativizing representational claims.

These approaches rely to different degrees on an understanding that meaning cannot be derived from a single document, but demands a complex interaction of images, texts and documents. Just as no document or artefact can directly supply evidence in isolation, photography is always contextually determined and connotative. In other words meaning is not immanent to individual documents or to the work of art itself, but is constructed through discursive and institutional conventions in the field of representation. Constructed through every publication and presentation context, through every reception, with every mode of reading and viewing; it is fluid, never fixed, it circulates and migrates. Or as Roland Barthes puts it: “The picture, whoever writes it, exists only in the account given of it; or again: in the total and the organization of the various readings that can be made of it: a picture is never anything but its own plural description.” [4] So “the object is polysemous, i.e., it readily offers itself to several readings of meaning; in the presence of an object, there are almost always several readings possible and this is not only between one reader and the next, but also, sometimes, within one and the same reader.” [5] Many of the more recent documentary practices relate productively to this polysemy by incorporating openness of meaning as a central moment.

The visible and the readable

Image/text combinations represent one mode through which current documentary projects draw out the context-dependency of meaning by combining and confronting different descriptive systems. My points of reference for this approach include among others the photobook projects by Edmund Clark, Regine Petersen and Max Pinckers as well as Eva Leitolf’s Postcards from Europe and Deutsche Bilder II. [6]

Text is employed in very disparate forms in these works, but generally on almost equal terms with the images. Allan Sekula wrote about this possibility in 1978, in Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation):

These artists, on the other hand, openly bracket their photographs with language, using texts to anchor, contradict, reinforce, subvert, complement, particularize, or go beyond the meanings offered by the images themselves. These pictures are often located within an extended narrative structure. [7]

[They] can be worked over and against each other, leading to the possibility of negation and meta-commentary. [8]

In other words, Sekula sees text offering a means to burst the bubble of photographic illusionism.

In terms of the relationship between images and texts, this process of combining and confronting recalls the “image/text problem” that W. J. T. Mitchell describes in his Picture Theory as “the heterogeneity of representational structures within the field of the visible and readable”. [9] Mitchell highlights the representational gulf between image and text using a typographical convention, putting a slash between the two. [10] His understanding of the relationship between the readable and the visible as an unstable dialectic, as laid out in Beyond Comparison: Picture, Text, and Method, generates a productive approach for reading the image/text combinations in current documentary narratives. [11] Referencing Foucault, Mitchell writes:

‘[W]ord and image’ is simply the unsatisfactory name for an unstable dialectic that constantly shifts its location in representational practices, breaking both pictorial and discursive frames and undermining the assumptions that underwrite the separation of the verbal and visual disciplines […]. [12]

With his unstable dialectic Mitchell puts his finger on something that is especially characteristic for the approaches to image/text combinations in the aforementioned projects. There are not classical journalistic captions, where the function of the text is generally to make the image concretely legible and narrow down the polysemy of the image. [13] Instead they tend to emphasise the disparateness of the visual and verbal levels. What this produces is a complex web of meaning with ambiguity at its heart. [14] Works like Laia Abril’s On Abortion (see above, footnote 3), which seek complementary contextuality in the combination of images and texts, occupy a kind of intermediate position here. They go further than the relay function of linguistic messaging and fixing of meaning sought by classical captions, but are ultimately still more concerned with legibility than ambiguity. On the other hand, in works that specifically emphasize the dialectic of visuality and textuality the relationship between image and text appears infinite in the way Foucault describes for the relationship between language and painting:

But the relation of language to painting is an infinite relation. It is not that words are imperfect, or that, when confronted by the visible, they prove insuperably inadequate. Neither can be reduced to the other’s terms: it is in vain that we say what we see; what we see never resides in what we say. And it is in vain that we attempt to show, by the use of images, metaphors, or similes, what we are saying […]. [15]

Especially where image/text combinations are looking more for ambiguity than legibility, they underline how images and texts cannot be brought into epistemological correspondence (as the classical caption seeks to do). Rather than indicating a dualism of image and text, they show that it is impossible to even think about images in isolation from textual signs and systems of meaning. Just as an image has no meaning without conceptual associations [16], recent documentary strategies emphasize the textuality of images, especially photography, and thus their embedding in discursive or institutional systems.

Of course the discussion about documentary forms working with image/text relations and the questioning of the relationships between visuality and textuality often associated with this are nothing new, and current trends specifically in the medium of the photobook (subsumed in various contexts under “research-based photobooks”) are certainly not their first occurrence.

Martha Rosler, from the series The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, 1974–75, gelatin silver prints, courtesy the artist

In the 1970s artists like Martha Rosler, Allan Sekula and also Victor Burgin [17] were already proposing a discourse on the renewal of the documentary. [18] In their practice, which addressed photography as a central medium of the debate, artists – especially Rosler and Sekula – sought to counter the prioritization of visual narratives by situating these in the context of intersecting discourses.

“Reinventing” the documentary [19]

At the beginning of the 1970s Allan Sekula and Martha Rosler, along with Fred Lonidier, Phil Steinmetz and Brian Connell, formed the San Diego Group at the Art Department of the University of California. [20] Rosler and Sekula realized the Group’s demand for new documentary forms in their artistic practice, in their own writings, [21] and not least in various interviews. Rosler called for a documentary practice capable of counteracting what she saw as a trend towards depoliticization:

We all felt, to one degree or another, that photography was held captive to outmoded ideas and forms of presentation […]. Together we sought a renovation of documentary practices away from the apparent complacency and de-politicization of the field as it was made visible within the mainstream art and photojournalistic worlds. [22]

Sekula also insisted that a “political critique of the documentary genre is sorely needed”. [23] Rosler and Sekula were driven by their own interest in accessing the social dimension through the medium of photography. [24] In seeking not only to represent the social but to incorporate its invisible dimensions, and in the process to comprehend photography itself as a social, political and discursive phenomenon, they expound a critique of the forms of classical photojournalism and documentary photography. It should be noted, though, that they certainly did not regard the latter as completely outmoded; rather than abolishing the documentary, they were calling for a critical reorientation of its strategies and practices. [25]

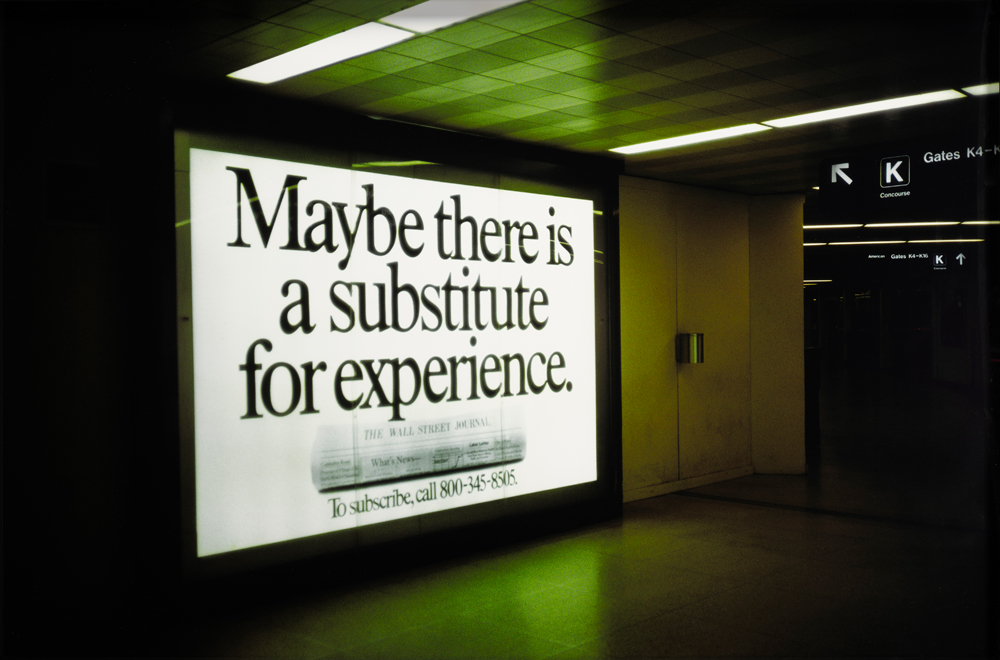

Martha Rosler, O’Hare (Chicago), 1986, from the series In the Place of the Public: Airport Series, ca. 1983-present, courtesy the artist

Rosler and Sekula’s foremost criticism of the traditional forms of photographic representation of the social revolved around the relationship between photographer and photographed (subject) articulated therein. Rosler saw this typified in the “‘parachuting photographer’, who would go somewhere, take pictures of some crisis, and get the hell out”. [26] The subject-object relationship cemented by that approach serves above all to establish the power of the photographer and viewer. Rosler frequently points out the concomitant problem of fixing the photographed in the position of the other.

Documentary is a little like horror movies, putting a face on fear and transforming threat into fantasy, into imagery. One can handle imagery by leaving it behind. (It is them, not us. [27]

Like Sally Stein and Abigail Solomon-Godeau, [28] Rosler sees normative subject-object relations creating a discrepancy between an intention to criticize prevailing conditions and their affirmation:

The exposé, the compassion and outrage, of documentary fueled by the dedication to reform have shaded over into combinations of exoticism, tourism, voyeurism, psychologism and metaphysics, trophy hunting – and careerism. [29]

Taking this to its logical conclusion, Solomon-Godeau observes:

We must ask […] whether the documentary act does not involve a double act of subjugation: first, in the social world that has produced its victims; and second, in the regime of the image produced within and for the same system that engenders the conditions it then re-presents. [30]

Sekula also notes the often limited critical possibilities of documentary forms, and their tendency to promote voyeuristic, fetishizing and exoticizing traits through a form of othering:

At the heart of this fetishistic cultivation and promotion of the artist’s humanity is a certain disdain for the ‘ordinary’ humanity of those who have been photographed. They become the ‘other’, exotic creatures, objects of contemplation. [31]

Sekula does not deny the possibility of documentary evidence. Ultimately he also shares the idea that visual and textual representations can say something meaningful about the world, although his understanding of the efficacy of the documentary is always tied to its contextuality. But he believes that the photographic promise of “having been there” presents a danger of voyeuristic exploitation of the subject, and points out how little documentary photography driven by humanism has historically contributed to a critical understanding of the world:

Documentary photography has amassed mountains of evidence. And yet, in this pictorial presentation of scientific and legalistic ‘fact’, the genre has simultaneously contributed much to spectacle, to retinal excitation, to voyeurism, to terror, envy and nostalgia, and only a little to the critical understanding of the social world. [32]

In his own work Sekula seeks a form of “project of a critical realism” [33], to “brush traditional realism against the grain” [34]. This, he believes, requires reflection on the conditions of construction of the documentary within a documentary practice that always understands representation as a process embedded in discursive and ideological formations:

Against the photoessayistic promise of ‘life’ caught by the camera, I sought to work from within a world already replete with signs. [35]

In that sense Sekula treats photography as a code to be learned and decoded: a form of interpretation rather than a medium faithfully recording reality. “Meaning, as an understanding of that presence, emerges from an interpretative act. Interpretation is ideologically constrained.” [36] I will now turn to Sekula’s Aerospace Folktales of 1973, to demonstrate how deeply these ideas are embedded in his own work.

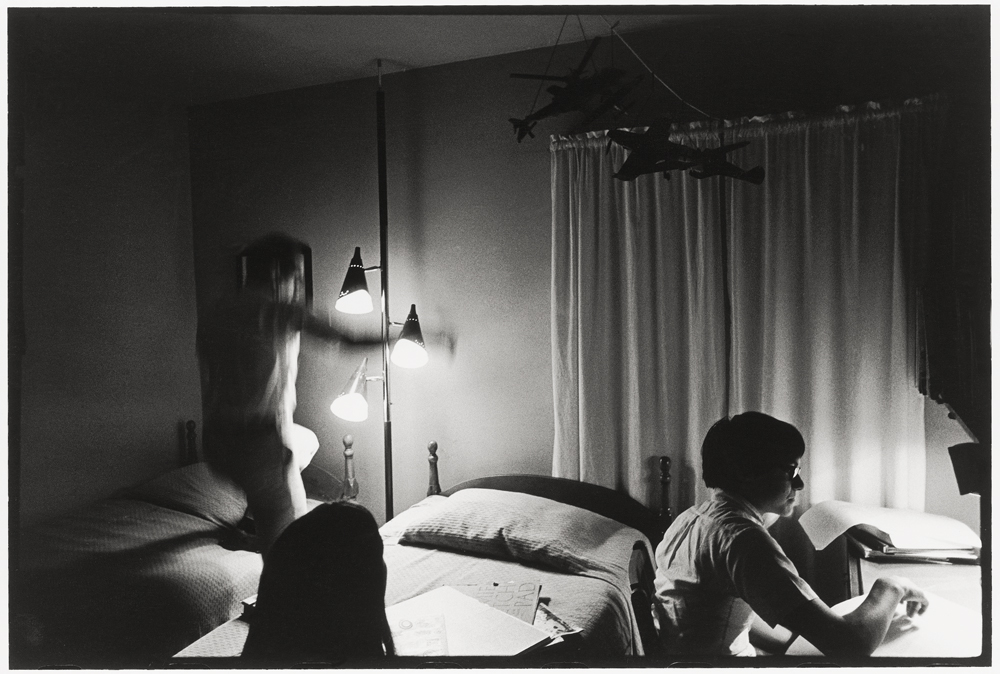

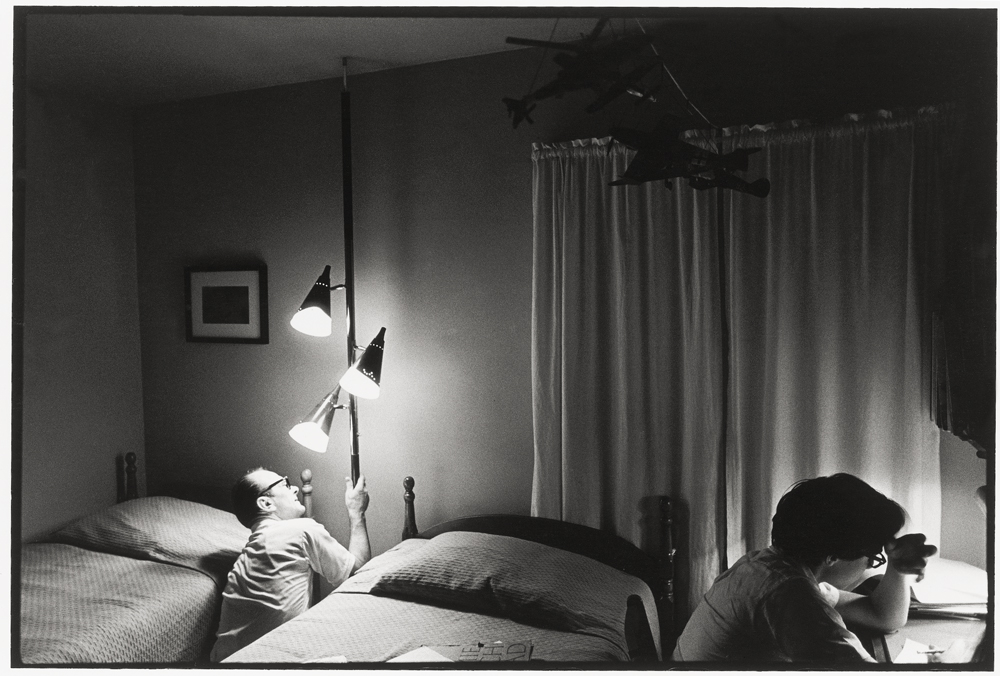

Aerospace Folktales – “parallel tracks for voice and image and text” [37]

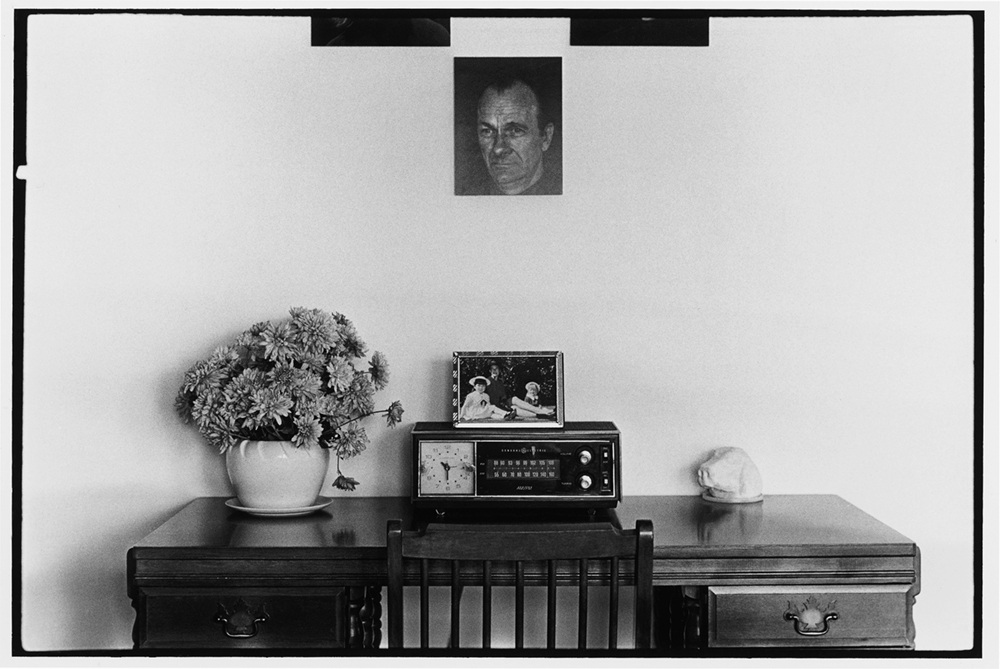

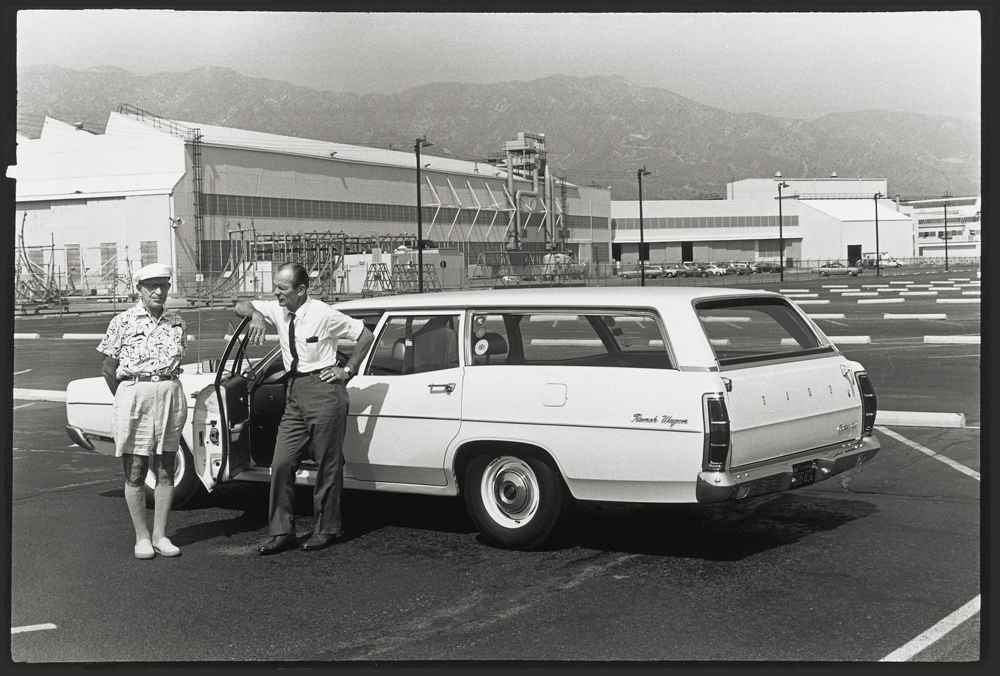

Sekula’s Aerospace Folktales ditches the primacy of the visual, choosing instead to combine photographs and texts. The project revolves around the story of an aerospace engineer who loses his job at Lockheed. The economic tribulations of the early 1970s are illustrated through the fate of a stereotypical “middle class” individual. In Aerospace Folktales Sekula brings together his own photographs of family scenes and others taken at the Lockheed factory with “found” visual material including historical family photographs and images that apparently originate from the company but are presented without any reference to their origins. Sekula’s montage strategy also integrates various documents including a typed CV of the kind usually used for job applications, a single page listing the “tenant policies” for “Marine View Apartments”, as well as photographed pages from a book about nuclear weapons and medical documents and prescriptions that identify neither a specific diagnosis nor the person receiving treatment. Apart from these photographed documents, two additional text levels feed into the process of contextualization.

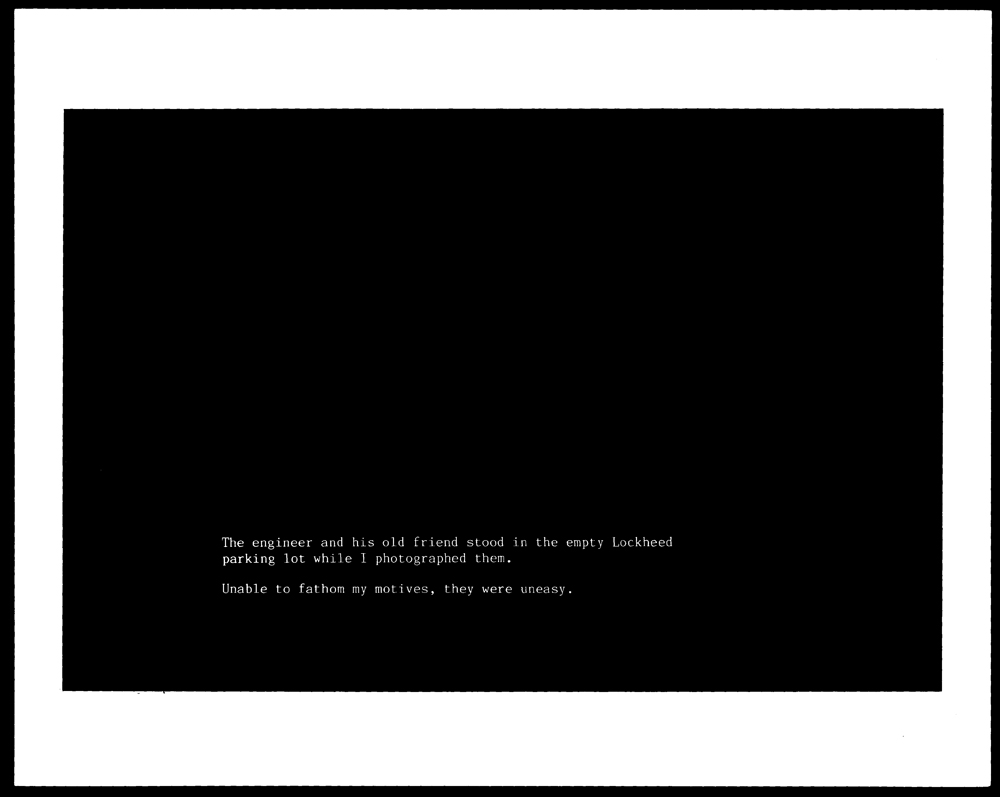

The first of these is the text panels. With white lettering on a black background, these have the same dimensions as the photographs and thus – although fewer in number – function as aesthetic equals. Aside from a single quote from a company publication from 1969, [38] the black text panels fulfill a function that recalls both classical captions and also the intertitles used in silent movies. They supply information about the people and objects, but also touch on the photographer’s perspective and his relationship to the photographed situation.

The second additional text level relates to the interviews, which were presented as audio recordings in the exhibition context. These include an interview with the engineer himself, an interview with his wife, and one with one of the wife’s friends, whose husband has also been made redundant. [39] In the first exhibition version of Aerospace Folktales the interviews were played in an adjacent room; in the later version the speakers were hidden behind pot plants in the middle of the exhibition space in which the rest of the work was also displayed. [40]

Allan Sekula, installation view of the series Aerospace Folktales, Brand Library Art Center in Glendale, California, 1974

There is also a fourth text level: this is Sekula’s written commentary, which he read himself at the first presentation of the work, at the University of California, San Diego. [41] This commentary, which is sometimes also exhibited at the end of the sequence of photographs, reveals that the portrayed family is Sekula’s own: the unemployed engineer is his own father.

The written commentary disrupts the quasi-archival compilation of materials and media and injects a personal perspective – as does the selection of motifs and the visual aesthetic of the photos, which evokes the personal, amateurish style of a family photo album. When Sekula began work on the project, he was “committed to the idea that a photographic project was of necessity a matter of editing and sequencing, of parallel tracks for voice and image and text”. [42] As he put it himself, the first version of Aerospace Folktales was therefore “a bit like a disassembled movie” [43]. The photographic sequence does indeed unfold as a quasi-filmic narrative, not only through intertitles reminiscent of the silent film era, but also through the very close sequencing of the photographs. This is especially obvious in the initial, more comprehensive edit, which places particular emphasis on describing individual everyday moments in great detail.

Sekula assembles a range of media including photographs, text and audio to build a complex web of different perspectives. For example he uses text to express different perspectives on the situation of unemployment: as well as his own these are those of his father and mother, whose respective voices are conveyed in Sekula’s interviews. The positions expressed by father and mother appear quite contradictory and largely gender-conforming, but complement one another to create a complex, multiperspectival understanding that guides the viewer away from monodimensionality. Mother describes unemployment from a very personal angle, while father’s narrative is much more distanced and seeks a more general social and economic perspective. Sekula uses his own commentary to describe his process of artistic reflection, for example when he outlines the process by which particular photographs were created. He also explains why he wanted to add a layer of text to the photographs:

but to a larger extent i am writing because of the limited representational range of the camera one cannot photograph ideology but one can make a photograph step back and say look in that photograph there is ideology between those two photographs there is ideology there is such and such and such relates to such. [44]

Other levels of the project also seek to emphasize its textuality and contextuality through various aspects of genesis and meaning. These include the personal perspective of the family scenes, a visual language reminiscent of corporate documentation, and the apparent facticity of the integrated documents, which replicate a juxtaposition of personal/subjective and distanced/objective perspectives that is also intimated in the interviews. Ultimately the factual level of the project, the economic situation of the United States at the beginning of the 1970s, is supplemented with a subjective perspective, while the personal family context addressed by the artist is subjected to a critical distancing.

Sekula’s relationship to the classical illustrated journalism typified by the visual language of Life magazine in the 1930s is ambivalent. In focussing on a single protagonist to represent a complex social issue he echoes that style. But he does so with an incidental narrative style that shuns spectacular individual images, creating a quite different outcome. Ultimately Sekula transcends classical reportage, embedding his photographic motifs in a complex narrative that – by combining image and text – not only presents the various media, levels and perspectives as mutually complementary but also shows them to be incoherent. Even if he relates his “parallel tracks” [45] primarily to the medium of the exhibition, Sekula anticipated developments of the narrative form that reappear more than forty years later in the medium of the photobook, with the confrontation of different materials and narrative levels. [46] In a similar way Sekula’s montagesque approach seeks to contradict the idea that one can capture the world in a mere photo. Instead he employs a multitude of visual and textual conventions in parallel to draw out “the incommensurability of the accidental dimensions of these factual intervals against the overcoded regularity of photojournalism and traditional documentary that always presume a perfect fit between the photography genre and the motif”. [47]

Two inadequate descriptive systems

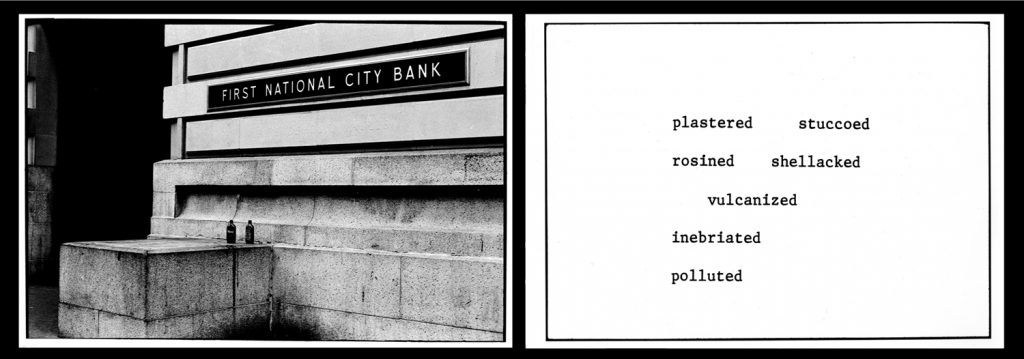

The critique of traditional documentary forms by emphasizing difference, which Sekula articulates through his montage of parallel tracks, also recurs in the work of Martha Rosler. In The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems, which she created in 1974–75, Rosler reflects in depth on the relationship between image and text and the possibilities of transporting reality attributed to them. The question of representation itself is already raised in the work’s title.

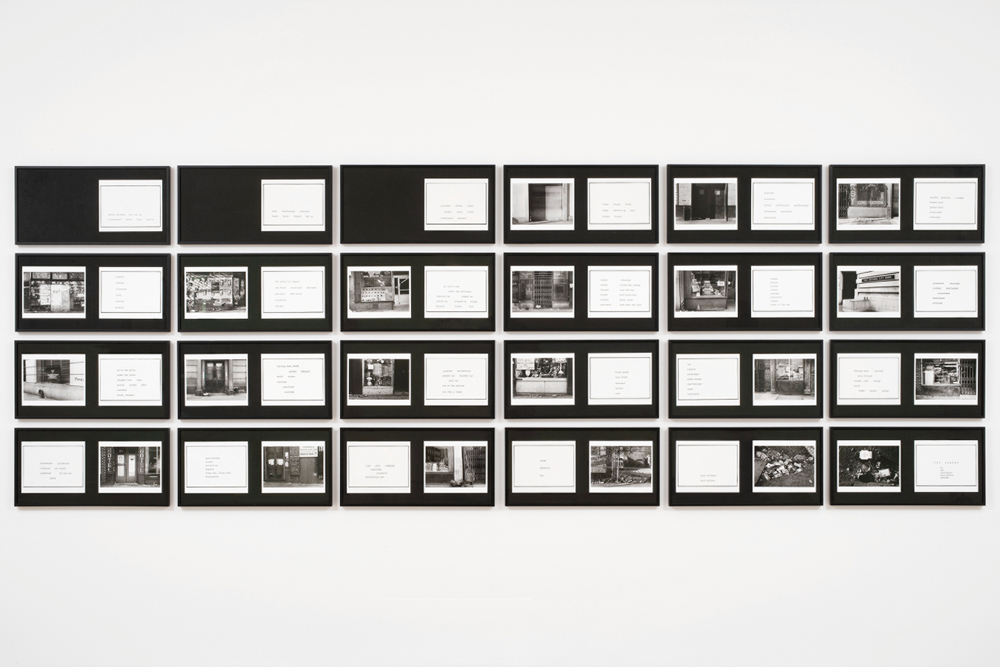

In December 1974 and January 1975 Rosler took black-and-white street photographs on the Bowery in Manhattan, which she combined with texts in the course of 1975 [48]. The work was originally conceived as an exhibit comprising twenty-one monochrome photographs and twenty-four text panels [49]. For wall display, photographic and text panels of identical size and format were arranged largely in pairs, mounted on black card in black frames and hung in the form of a grid. [50]

Martha Rosler, installation view of the series The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, 1974–75, gelatin silver prints © Noel Allum

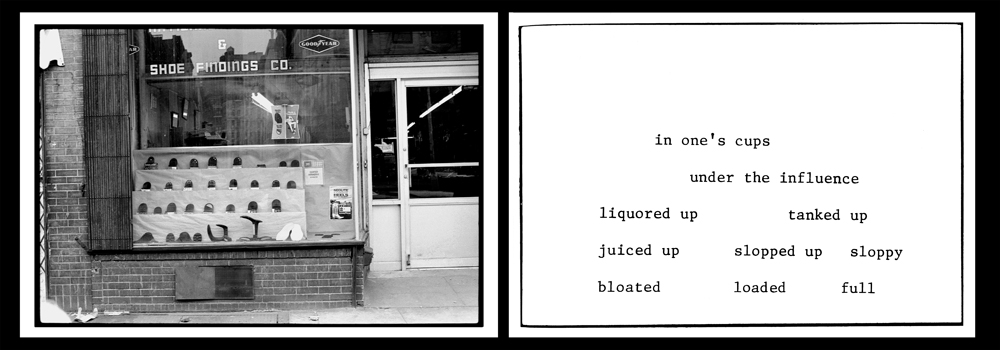

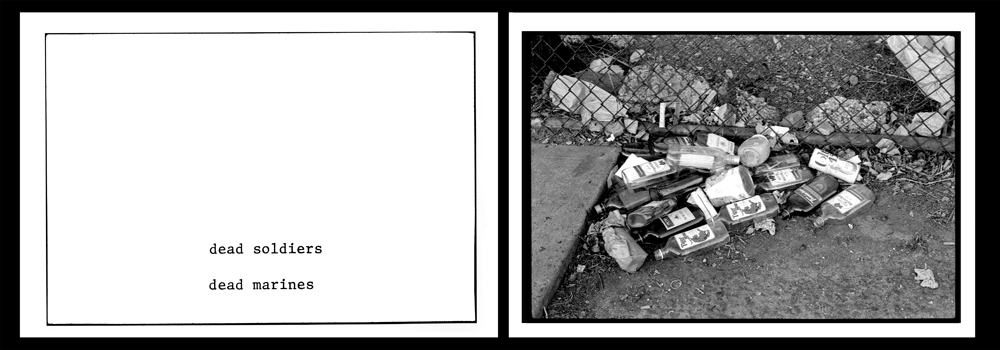

The first three frames in the top row had just a black rectangle to the left of each text panel in place of a photograph. It is also notable that the strict order of the grid breaks after thirteen photo/text pairs, when the photos switch from the left to the right-hand side. Most of the photographs show frontal images of closed shopfronts and doors, barred windows and entrances, while the text panels feature words relating to inebriation. The arrangement of the words is suggestive of poetry. Two groups can be identified.

The first sixteen text panels contain adjectives, whose place is taken by nouns after the panels switch to the left-hand side. The degree of drunkenness evoked by the words also appears to increase in the course of the sequence of twenty-four text panels. The series begins with synonyms describing a state of mild merriness and ends with metaphors for extreme intoxication such as “dead soldier” and “dead marines”.

The photographs also convey the theme of alcohol(ism). Aside from the liquor bottles on the ground, the location where the photographs were taken also serves this function – the Bowery in the 1970s was, as Martha Rosler herself put it:

[…] an archetypal skid row. It has been much photographed, in works veering between outraged moral sensitivity and sheer slumming spectacle. Why is the Bowery so magnetic to documentarians? It is no longer possible to evoke the camouflaging impulses to ‘help’ drunks and down-and-outers or ‘expose’ their dangerous existence. [51]

So with the Bowery Rosler explicitly chose a classical subject of social documentary photography, only to counterpose her own narrative mode. Her central aim is an artistic exploration of structural critiques of the dominant documentary discourse. So what strategies was she using?

Martha Rosler, from the series The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, 1974–75, gelatin silver prints, courtesy the artist

One central aspect is the absence of people [52]. This is characteristic of Rosler’s photographs of the Bowery, and distinguishes them from the often humanism-driven classical documentary and photojournalism. Today too, the absence of people continues to play a central role in the search for new documentary narrative forms. For example in the work of artists like Eva Leitolf and Edmund Clark, both of whom place great store in the concept of conveying complex issues via places and their topographies. The focus on place enables a form of narrative that departs from the idea of employing individual protagonists as representatives for complex social relations and situations, not least in response to Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s “double act of subjugation”. While certainly regarding itself as socially motivated, such an understanding of the documentary rejects the idea of narrating via the concrete and singular – which could indeed be conveyed especially well via the medium of photography and the specific visibility it is able to generate.

“But there aren’t any people in that piece because how do you adequately represent the experience of other people? That was the main problem.” [53] In the visual part of The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems Rosler shows only places that typify the massive housing shortage and social problems of 1970s New York, which turned the Bowery into a “skid row” [54]. Her photographs characterize the Bowery as the antithesis of a lively, prosperous quarter. Most of the shops appear closed, the entrances are often barred, the windows boarded up; more storeroom than display front. Echoing the lack of human figures, the closedness of the façades, the strict frontality of the perspective and the tightness of the framing underline the impression of absence. Despite the lack of visible protagonists, there is certainly evidence of their presence. The sidewalks and entrances are littered with empty bottles, trash, and even a pair of seemingly abandoned shoes. These refer metonymically to the invisible people who apparently otherwise populate these places. They tell of the absence of presence and the presence of absence. In her use of the medium of photography here, Rosler is apparently less interested in making something visible than in using the medium of visibility specifically to emphasize that something remains unseen. The first three frames in the wall presentation appear to explicitly visualize this invisibility, showing empty black space rather than photographs next to the text panels [55]. The absence of the protagonists reflects their social marginalization; above all the images generate distance – as opposed to the emotionalization and dramatization of humanist social documentary photography [56]. So what is Rosler’s project talking about if it is not communicating poverty, neglect and alcoholism as a pitiful individual plight? This question cannot be answered exclusively on the visual level, because image and text figure as equals in Rosler’s work.

Martha Rosler, from the series The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, 1974–75, gelatin silver prints, courtesy the artist

And not only in formal terms of the size of the images and the number of panels. Unlike classical captions in the journalistic context Rosler’s texts convey no descriptive information; they are not designed to augment or clarify the legibility of the photographs. The adjectival and nounal fields create a metaphorical realm of association to which the empty bottles in the photographs also allude. But the connotations of the words project far beyond the images and tend to expand rather than shrink the semantic space. Ultimately in fact Rosler reverses the conventional journalistic relationship between image and caption, where emotive images are often qualified with objective descriptive and explanatory texts that operate more in the factual than the metaphorical dimension. In her combination of image and text Rosler consciously exploits the incoherence of the two descriptive systems to which the title also alludes. Even if the title appears at first glance to refer directly to the significance of the text/image relation for the work, certain aspects remain unclarified. One may legitimately wonder whether it is really two systems, what characterizes them, and in what sense they could be inadequate. The most obvious systematization in Rosler’s work is to read the image and text levels as references to the respective descriptive system. Rosler herself suggested something similar in an interview with Benjamin Buchloh:

“‘Inadequate’ to what?”

“A descriptive system; descriptive systems are inadequate to experience. But then the question is, what is experience?”

“You are using two descriptive systems. So they are both inadequate.”

“Well, aren’t they?” [57]

So Rosler wants the title to lend the project a central reference to a metalevel reflecting on the work itself. Ultimately the title represents the fulcrum for reading the work as a form of documentary practice that articulates the critical perspective on the documentary as part of the work. Referring to Rosler’s work, Sekula speaks of a “metacritical relation to the documentary genre” [58]. Rosler sees the inadequacies of the descriptive systems word and image less in their relationship to one another than in the difference between the descriptive system and the experience. “[T]he answer is that fundamentally there is an incommensurability between experience and language. I don’t think that any system of representation is adequate.” [59] This approach of Rosler’s is motivated by a critique of humanist photojournalism: “[W]hat was moving me more was the underlying humanist notion of the commensurability between representation and experience and even its optimistic view of progress.” [60] For this reason Rosler has repeatedly described The Bowery as “a work of refusal”: [61]

The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems is a work of refusal. It is not defiant antihumanism. It is meant as an act of criticism […]. If impoverishment is a subject here, it is more centrally the impoverishment of representational strategies tottering about alone than that of a mode of surviving. The photographs are powerless to deal with the reality that is yet totally comprehended-in-advance by ideology, and they are as diversionary as the word formations […]. [62]

Rosler’s interpretation points, via the topic of impoverishment, to an understanding of the documentary that seeks to incorporate both the representation of politics and the politics of representation [63]. As Sekula also puts it: “The object of the work, its referent, is not the Bowery per se, but the ‘Bowery’ as a socially mediated, ideological construction.” [64] But how does The Bowery actually operate on the image/text level as a work of refusal and as a work addressing the process of representation itself? Strategies of refusal are found in The Bowery not only in the sidelining of photojournalistic criteria like closeness and emotionality but also through an aesthetic that repudiates the idea of the “powerful image”. Rosler always explicitly opposed an overly aesthetic reverence for the image, which is one reason why she often designed her works not primarily for the art and gallery context but published them as videos or even postcards. [65] To Rosler the artistic interest in aestheticization discourses appeared especially obvious in “[t]he modernist paradigm of pure visuality” [66], which she felt was associated with “the denial of content” [67] and “the denial of the existence of the political dimension” [68], and thus also a denial of their contextuality. Instead Rosler saw a “dialectical relation between political and formal meaning” [69], which left no place for a “non-ideological aesthetic” [70]. But Rosler conceived The Bowery explicitly for the gallery context and thus for a publishing situation that she tended to avoid with her other works, not least on account of her criticisms of the art market. In the case of The Bowery the gallery offered her a context for a critical strategy [71]. Over and above the institution of the art gallery and its specific contexts, her choice of presentation in grid form rejects the focus on the individual image and its auratisation and essentially emphasizes the contextuality of the photographs. Rosler herself compares the grid to industrial mass production:

It [the grid] invokes the industrial processes of mass production […] decreasing the value of the individual object or ‘utterance’, avoiding the fetishization of the unique or ‘folkish’ object. It can lower emotional temperature as well. [72]

Martha Rosler, installation view of the series The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, 1974/75, at Documenta 12, 2007

Her critique of the “organismic pleasure afforded by the aesthetic ‘rightness’ or well-formedness (not necessarily formal) of the image” [73] and “the gigantic ideological weight of classical beauty” [74] resurfaces in the formal composition of the individual photographs in The Bowery. In response to accusations that her photographs were “unoriginal” [75], she has consistently described them as quotes from a particular photographic tradition, explicitly mentioning Walker Evans [76]. Another aspect that appears to me even more significant than the quote function is the way she plays with the aesthetic imperfection of the photographs [77], whose composition and lack of parallelism (despite their frontality) appear to negate the ideals of technical competence that are so central to the photojournalistic discourse of the “good image”. Sekula also consciously employed sequencing to escape a reception that was “only on the prowl for individual ‘good’ and ‘bad’ images” [78]. Rosler and Sekula opposed both the fetishization of the image and the elevation of the artist. Rosler’s consistent feminist pushback against the concept of coherent artistic subjectivity led her to conclude: “I don’t want people to engage with the persona of the creator.” [79] Sekula points to the danger of depoliticization associated with recognition of the documentary as art, the associated role of the artist and the significance of the art market:

A curious thing happens when documentary is officially recognized as art. […] Suddenly the audience’s attention is directed toward mannerism, toward sensibility, toward the physical and emotional risks taken by the artist. Documentary is thought to be art when it transcends its reference to the world, when the work can be regarded, first and foremost, as an act of self-expression on the art of the artist. [80]

For Sekula, “the key question […] is whether the meaning-structure of the work spirals inward toward the art-system or outward toward the world” [81]. Rosler’s rejection of the primacy of the visual can also be understood as a form of refusal that emphasizes the divergence of image and text. The difference between representation and experience is also reflected in Rosler’s art: in its tension between visuality and textuality The Bowery demonstrates “that there is always a meaning which overflows the object’s use” [82]. The image and text levels in The Bowery (and their combinations) are consistently polysemous. Especially in the confrontation of images and texts – and by exposing the “suturing of one medium to the other” [83] – Rosler opens up, in a manner similar to the montage principle, an in-between that eludes any firm attribution of meaning. In other works Rosler also operates with the interstices, vacancies and indeterminacies generated by the confrontation of different levels of representation. In her early photomontage series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home she explicitly set out to connect places by montaging war photographs from Vietnam with domestic interiors from American lifestyle magazines. [84] These visually ambiguous combinations of different visual mass media genres, which Rosler originally produced for political magazines, serve a primarily educational objective here – revealing the interconnectedness of apparently completely separate worlds. House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, unlike The Bowery, functions as a form of anti-war activism through the moment of shock triggered by the confrontation of opposites: private and public, the ideal aesthetic of advertising and the brutal reality of war.

Martha Rosler, Cleaning the Drapes, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, ca. 1967–72, photomontage, courtesy the artist

The confrontation of levels in House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home finds its conceptual resolution in a clear anti-war message: the gaps in the process of reception can be closed. In The Bowery they remain disconnected to the last.

Context matters

I should not have to argue that photographic meaning is relatively indeterminate; the same picture can convey a variety of messages under differing presentational circumstances. [85]

Both in their artistic works, which draw on diverse medialities and materialities, and in their theoretical explorations, Rosler and Sekula have undertaken exhaustive explorations of the critical potential of documentary narrations since the early 1970s. Their starting point was the question of how photographs work and what possibilities they offer for a critique of social conditions. In their explorations of the mediality of photography Rosler and Sekula were always concerned with repoliticising and realigning the institutional and discursive strategies of the documentary. Both in the process problematised the limits of purely visual forms of representation and distanced themselves from an idea rooted solely in the evidential nature of photography. By combining different media strategies in their works they instead pursue the heterogeneity of evidence and documentation to open up fields of mutually complementary and reciprocally relativizing representational claims. In so doing they lay out, especially in their handling of image and text, strategies that resurface in today’s discussions about the so-called research-based photobook. For Rosler and Sekula the documentary emerges not exclusively via the visual, whose power they seek to delegitimize, but in the complex interaction of visual and textual levels. While acknowledging the limits of individual segments of reality, Rosler and Sekula are both ultimately seeking an effective documentary practice and an associated connection to the real. In this practice contextuality functions as a precondition for any form of significance or efficacy. In The Bowery and Aerospace Folktales Rosler and Sekula harness the openness of the structures of meaning to emphasize the incoherence and incommensurability of the different levels of representation. For them text and image function as a form of contextualization, which tests not only the possibilities and limits of the representable but also the fundamental relationship between representability and presence of the represented. This becomes clear when something is made visible or readable and at the same time – for example through the contrast of image and text levels or the absence of people in The Bowery – the limitedness of the visible and readable is demonstrated. In awareness of the limited nature of the mediated excerpt of reality the viewer is drawn into a process of construction of meaning that communicates how representation generates both presence and absence. In that sense the works of Rosler and Sekula not only tell of social problems such as poverty, alcoholism and unemployment but also reflect on the mechanisms of representation and their entanglement in processes of power and politics. This form of reflection is further amplified in their own theoretical texts in which they discuss their works and place them in a broader context [86]. Ultimately the contextualization in the theoretical texts also relativizes – however partially – the openness for which the works stand by supplying (or at least suggesting) more specific readings.

In their understanding of the documentary, which presupposes reflection on its conditionality as part of their own practice, Rosler und Sekula turn out to presage today’s debates. Current works break radically with an understanding of the documentary as a visually evidenced promise of actuality. They see the documentary instead as a context-based system, characterized by its need for continuous questioning and confirmation.

Karen Fromm is Professor at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Hanover. Her areas of research and teaching are photo theory, pictorial languages and the documentary. In the past she managed the Galerie Pfefferberg in Berlin and was a member of the management of the FOCUS photography and press agency. She has founded the platform [IMAGEMATTERS] and edited the volumes Images in Conflict (2018) and image/con/text. Documentary Practices between Journalism, Art and Activism (2020). Karen is director of the LUMIX Festival for Young Visual Journalism.

[1] “We … believe that context matters.” “Martha Rosler in Conversation with Nina Möntmann, 17 December 2003”, in: Nina Möntmann and Dorothee Richter (eds.), Die Visualität der Theorie vs. die Theorie des Visuellen: Eine Anthologie zur Funktion von Text und Bild in der zeitgenössischen Kultur, Frankfurt am Main 2004, pp. 97–103, here p. 100.

[2] A German version of this essay is published in: Karen Fromm, Sophia Greiff, Malte Radtki and Anna Stemmler (eds.), image/con/text. Dokumentarische Praktiken zwischen Journalismus, Kunst und Aktivismus, Berlin 2020, and Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net, 2020, https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.674.

[3] I would regard Mathieu Asselin’s Monsanto®: A Photographic Investigation, published in book form in 2017, as one example of such an investigative approach. Mathieu Asselin, Monsanto®: A Photographic Investigation, Dortmund 2017. I would also tend to include Laia Abril’s photobook On Abortion which operates with additional and complementary contextuality rather than open structures of meaning. See also “Beneath the Surface. Laia Abril in Conversation with Sophia Greiff”, in: Fromm, Greiff, Radtki, Stemmler (eds.), image/con/text. Dokumentarische Praktiken zwischen Journalismus, Kunst und Aktivismus, 2020, pp. 150–161, and Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net, 2020, https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.674 (accessed 25 January 2020).

[4] Roland Barthes, “Is Painting a Language?”, in: Roland Barthes, The Responsibility of Forms: Critical Essays on Music, Art, and Representation, Berkeley/Los Angeles 1991, pp. 149–152, here p. 150 (emphasis in original).

[5] Roland Barthes, “Semantics of the Object”, in: Roland Barthes, The Semiotic Challenge, London 1988, pp. 179–190, here p. 188.

[6] For a more detailed discussion see also: Fromm, Greiff, Radtki, Stemmler (eds.), image/con/text. Dokumentarische Praktiken zwischen Journalismus, Kunst und Aktivismus, 2020, and Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net, 2020, https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.674.

[7] Allan Sekula, “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)” [1978], in: Allan Sekula, Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works 1973–1983, London 2016, pp. 53–75, here p. 60. Under “these artists” Sekula discusses works from the 1970s by Martha Rosler, Philip Steinmetz and Fred Lonidier.

[8] As Sekula (ibid., p. 62) explains using the example of interaction of media as different as film, video, audio, still image and text.

[9] W. J. Thomas Mitchell, “Beyond Comparison: Picture, Text, and Method”, in: W. J. Thomas Mitchell, Picture Theory: Essays on verbal and visual representation, Chicago/ London 1994, pp. 83–109, here p. 88.

[10] Cf. ibid., p. 89.

[11] Mitchell has often been criticised for his demand – in connection with the pictorial turn – for “a postlinguistic, postsemiotic rediscovery of the picture” (W. J. T. Mitchell, “The Pictorial Turn”, Artforum 30, No. 7 [March 1992], pp. 89–94, here p. 91), and especially for a problematic generalisation of the concept of the image, because he rejects analytical approaches that expose the textuality of images and thus negates their argument against a dualism of text and image (of the kind that dominates for example in the work of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing) and their emphasis that image and text are fundamentally connectable. On the criticisms of Mitchell’s approach see among others Sabeth Buchmann, “Richtig ist anderes”, in: Nina Möntmann and Dorothee Richter (eds.), Die Visualität der Theorie vs. die Theorie des Visuellen: Eine Anthologie zur Funktion von Text und Bild in der zeitgenössischen Kultur, Frankfurt am Main 2004, pp. 45–54, and Jens Bonnemann, “Ein Anti-Lessing oder Die fragwürdige Ehe von Bild und Sprache – W. J. T. Mitchells Bildtheorie (Review of: W. J. T. Mitchell, Bildtheorie. Hrsg. und mit einem Nachwort von Gustav Frank. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp 2008)”, in: JLTonline, http://www.jltonline.de/index.php/ reviews/article/view/145/452 (accessed 13 January 2020). Although I share the critique of Mitchell’s position on the pictorial turn, the idea of the unstable dialectic of image and text appears productive for my investigations.

[12] Mitchell, “Beyond Comparison: Picture, Text, and Method”, 1994, p. 83.

[13] Walter Benjamin and Roland Barthes also discuss this function of captions. Walter Benjamin mentions “the directives which the captions give to those looking at pictures in illustrated magazines”. Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, in: Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn, New York 1969, pp. 1–26, here p. 8, https://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/benjamin.pdf (accessed 28 September 2020). Roland Barthes also discusses the meaning-assigning function of captions in the sense of the “anchorage” and “relay” functions of the linguistic message in relation to the visual. Roland Barthes, “Rhetoric of the Image”, in: Roland Barthes, Image, Music, Text, translated by Stephen Heath, New York 1982, pp. 32–51, here p. 38. “When it comes to the ‘symbolic message’, the linguistic message no longer guides identification but interpretation, constituting a kind of vise which holds the connoted meanings from proliferating, whether towards excessively individual regions (it limits, that is to say, the projective power of the image) […].” Roland Barthes, “Rhetoric of the Image”, 1982, p. 39.

[14] On ambiguity see among others Verena Krieger, “Strategische Uneindeutigkeit: Ambiguierungstendenzen ‚engagierter‘ Kunst im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert”, in: Rachel Mader (ed.), Radikal ambivalent: Engagement und Verantwortung in den Künsten heute, Zürich/Berlin 2014, pp. 29–56.

[15] Michel Foucault, “Las Meninas”, in: Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archeology of the Human Sciences, New York 1994, pp. 3–16, here p. 9.

[16] In de Saussures’s semiology image and text are already interwoven via the sign structure, “showing us that the linguistic unit is a double entity, one formed by the associating of two terms”. Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, New York/Chichester, West Sussex, 2011, pp. 65–70, here p. 65. As Sigrid Schade explains, “without this duality […] a ‘term’ is not a sign capable of meaning in the absence of things”. She continues: “Semiology investigates sign systems within which text and image are already conceived in inextricable – although not always visible – relation to one another.” Translated from Sigrid Schade, “Vom Wunsch der Kunstgeschichte, Leitwissenschaft zu sein: Pirouetten im sogenannten ‚Pictorial Turn‘”, in: Nina Möntmann and Dorothee Richter (eds.), Die Visualität der Theorie vs. die Theorie des Visuellen: Eine Anthologie zur Funktion von Text und Bild in der zeitgenössischen Kultur, Frankfurt am Main 2004, pp. 31–43, here pp. 41 f.

[17] On concepts of authorship in the practice of Rosler, Sekula and Burgin, see among others Alexander Streitberger, “‘Cultural Work as a Praxis’: The Artist as Producer in the Work of Victor Burgin, Martha Rosler, and Allan Sekula”, in: Alexander Streitberger and Hilde Van Gelder (eds.), “Disassembled” Images, Leuven 2019, pp. 192–211.

[18] See also Abigail Solomon-Godeau, “Who Is Speaking Thus? Some Questions about Documentary Photography”, in: Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Photography at the Dock. Essays on Photographic History, Institutions, and Practices, Minneapolis 1997, pp. 169–183, here p. 171.

[19] Referring to the following quote from Allan Sekula: “This made it all the more important to take on the challenge of ‘reinventing’ documentary in ways that departed from the social documentary tradition, from art photography, and from the conceptual document.” Allan Sekula and Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “Conversation”, in: Allan Sekula: Performance unter Working Conditions, edited by Sabine Breitwieser, Vienna 2003, pp. 20–55, here p. 39.

[20] On the San Diego Group see among others Benjamin Buchloh, “A Conversation with Martha Rosler”, in: Martha Rosler: Positions in the life world, Birmingham 1998, pp. 24–56, here esp. p. 32; also Steve Edwards, Martha Rosler: The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems, London 2012, here esp. pp. 97 ff.

[21] See esp. Martha Rosler, “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)”, in: Martha Rosler, Martha Rosler, 3 works, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, 2006, pp. 61–93; Martha Rosler, “afterword: a history” (2006), in: Martha Rosler, Martha Rosler, 3 works, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada 2006, pp. 94–103; also Martha Rosler, Decoys and Disruptions, Selected Writings, 1975–2001, Cambridge, Massachusetts/London, England, 2004. On Sekula’s investigations of the documentary see among others Sekula, “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)”, 2016, and Sekula and Buchloh, “Conversation”, 2003, as well as Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “Allan Sekula: Photography between Discourse and Document”, in: Allan Sekuka, Fish Story, Düsseldorf 2002, pp. 189–200.

[22] “Martha Rosler in Conversation with Nina Möntmann, 17 December 2003”, 2004, p. 99.

[23] Sekula, “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)”, 2016, p. 58.

[24] “The most urgent need was to reintroduce the social dimension that had been repressed.” Sekula and Buchloh, “Conversation”, 2003, p. 27. Also Martha Rosler: “None of us wanted to reduce the engagment of art with real-world issues but rather to try to figure out how to renovate and reinvent forms.” Buchloh, “Conversation with Martha Rosler”, 1998, p. 46.

[25] “The recent prominence of documentaries suggests the durability of the form. I can only point again to ‘in, around, and after-thoughts’ itself, which demanded not the end of documentary but the renegotiation of its strategies and its surroundings, both institutional and discursive. I am not the kind of postmodernist who thinks there can be no universals and no judgements. I too am a partisan.” Rosler, “afterword: a history”, 2006, p. 103. “But as far as the Bowery essay was concerned, excoriating documentary as it was then practiced was necessary to moving it forward. But many people all round the world, it seems, have read the essay to mean that documentary should be abandoned! That’s not what I meant! We needed to renovate, reinvent, and recapture documentary.” “Martha Rosler in Conversation with Molly Nesbit and Hans Ulrich Obrist”, in: Martha Rosler: Passionate Signals, edited by Inka Schube, Hanover 2005, p. 6–63, here p. 28.

[26] Buchloh, “Conversation with Martha Rosler”, 1998, p. 46.

[27] Rosler, “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)”, 2006, p. 75 (emphasis in original).

[28] See Solomon-Godeau, “Who Is Speaking Thus? Some Questions about Documentary Photography”, 1997, and Sally Stein, “Making Connections with the Camera: Photography and Social Mobility in the Career of Jacob Riis”, in: Afterimage 10 (1983), pp. 9–16. Also my own contribution: Karen Fromm, “Die Unsichtbarkeit des Rahmens oder die Lesbarkeit von Welt”, in: Karen Fromm, Sophia Greiff and Anna Stemmler (eds.), Images in Conflict / Bilder im Konflikt, Kromsdorf/Weimar 2018, pp. 266–300.

[29] Rosler, “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)”, 2006, p. 75.

[30] Solomon-Godeau, “Who is Speaking Thus? Some Questions about Documentary Photography”, 1997, p. 176.

[31] Sekula, “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)”, 2016, p. 59.

[32] Ibid., p. 57.

[33] See among others Buchloh, “Allan Sekula: Photography between Discourse and Document”, 2002, p. 198.

[34] Sekula, Photography against the Grain, 2016, p. xii.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Sekula, “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)”, 2016, p. 53.

[37] Sekula and Buchloh, “Conversation”, 2003, p. 25.

[38] Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, Days of Trial and Triumph: A Pictorial History of Lockheed, Burbank, California, 1969, p. 8. Sekula does not give an exact location or page number.

[39] When first published the work comprised 142 black-and-white photographs and text cards, and four interviews. The images were divided into narrative sequences but displayed in a single line. Later, after Sekula had reduced the work to a selection of 51 photographs, the images were sometimes presented in groups or as a block. The interviews with the engineer and his wife are reproduced in: exh. cat.: Allan Sekula: Performance under Working Conditions, edited by Sabine Breitwieser, Ostfildern-Ruit/Vienna 2003, pp. 136 ff.

[40] My analysis is based principally on the version presented in the exhibition catalogue Allan Sekula: Performance under Working Conditions, which was developed from informal presentations using two slide projectors. See Allan Sekula: Performance under Working Conditions, 2003, pp. 92–163. For an impression of other presentation forms, see the website of the Generali Foundation http://foundation.generali.at/de/sammlung.html#work=4714& artist=186 (accessed 22 December 2019).

[41] The commentary is reproduced in: Allan Sekula: Performance under Working Conditions, 2003, pp. 144 ff.

[42] Sekula and Buchloh, “Conversation”, 2003, p. 25.

[43] Sekula, Photography Against the Grain, 2016, p. 106.

[44] Ibid., p. 164.

[45] Sekula and Buchloh, “Conversation”, 2003, p. 25.

[46] Only later did Sekula produce a photocopied photobook that was also exhibited. On the early exhibition history see Sekula, Photography Against the Grain, 2016, p. 106. In this connection it would be interesting to investigate why current developments gravitate specifically towards the medium of the photobook. It is also significant that in terms of complementarity of source types recent works integrate an even broader diversity of different documents, materials and found footage than did Sekula and Rosler.

[47] Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “Allan Sekula: Photography between Discourse and Document”, in: Allan Sekula, Fish Story, Düsseldorf 2002, pp. 189–200, here p. 199. This process, which Buchloh describes as “Sekula’s paradox of a ‘realistic montage’” (Buchloh, “Allan Sekula: Photography between Discourse and Document”, 2002, p. 199) can also be applied to Sekula’s later project Fish Story. Lacking the space here to address Fish Story in detail, I note merely that an exploration would appear very promising especially in relation to the issue of new narrative strategies in the documentary.

[48] For one detailed description of the process see: Edwards, Martha Rosler: The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems, 2012.

[49] The complete work was published in book form in Martha Rosler, 3 works, 2006. Rosler said she was happy about this, although she had not originally intended to publish it as a book. See Buchloh, “Conversation with Martha Rosler”, 1998, p. 44.

[50] Various exhibition configurations have been used, with panels measuring 10 x 22 or 10 x 24 inches and arrangements of 6 x 6, 4 x 6 or 5 x 5 frames.

[51] Rosler, “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)”, 2006, p. 73.

[52] In 1989 Rosler realised If You Lived Here… in cooperation with the New York homeless project Homeward Bound, working in the exhibition medium with artists, film-makers, squatters and homeless people. For the duration of the exhibition the homeless people lived in the Dia Art Foundation’s exhibition space, as Rosler told me by e-mail (of 16 February 2020): “The beds were in a section of the gallery separated by a partial wall from the rest of the show (it was about 1/4 or 1/5 of the space).” Here Rosler contradicts Adair Rounthwaite, who writes that it was ultimately not possible to realise the original idea of having the protagonists present in the exhibition space: “[…] the beds which Rosler originally placed in the gallery remained part of the installation after Dia made clear that the group was not allowed to sleep in the space. Stripped of their intended purpose, the beds retained a representational function of presenting the gallery as if it were a homeless shelter.” Adair Rounthwaite, “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (on Participation): Photography and Agency in Martha Rosler’s Collaboration with Homeward Bound”, in: Art Journal 73, No. 4 (2 October 2014), pp. 46–63, here p. 54. In other words, Rosler followed the absence of people in The Bowery with a work – If You Lived Here… – in which the people themselves were present. On If You Lived Here… see also Marjorie Welish, “Word into Image”, Bomb 47 (1994), http://www.jstor.org/stable/40425047 (accessed 28 August 2019), and also Martha Rosler, irrespective, New York: The Jewish Museum, 2018, pp. 162–171.

[53] Buchloh, “Conversation with Martha Rosler”, 1998, p. 45.

[54] Rosler, “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)”, 2006, p. 73.

[55] In the book presentations in Martha Rosler, 3 works (2006) this effect of emptiness is transported by blank white pages, to the left of each text panel in place of a photograph. The effect of emptiness is less present here. The filmic associations generated by black pages – which like Sekula’s text panels in Aerospace Folktales recall the cinematographic fade-to-black – are amplified by their correspondence to Rosler’s 1977 video work Vital Statistics of a Citizen, Simply Obtained. This 39-minute video begins with a voice-over while the screen remains black for almost two minutes. As the speaker in the voice-over, Rosler makes perception and representation themselves the work’s subjects: “This is a work about perception; there is no image on the screen just yet […].” The video can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b91_ vZ8TauM (accessed 29 December 2019).

[56] See also Rosler’s statement in her interview with Benjamin Buchloh: “The work intended a structural critique, yet without high drama or human actors. Only banks, storefronts, and empty bottles. The photos are really deadpan in that the building fronts are mostly totally flat against the picure plane […].” Buchloh, “Conversation with Martha Rosler”, 1998, p. 42.

[57] Ibid., p. 44.

[58] Sekula, “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)”, 2016, p. 60.

[59] Buchloh, “Conversation with Martha Rosler”, 1998, p. 45. Here, interestingly, Rosler does not differentiate between photography and language, but treats photography as a form of language.

[60] Ibid., p. 44.

[61] Rosler, “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)”, 2006, p. 86.

[62] Ibid. (emphasis in original).

[63] See also Solomon-Godeau, “Who Is Speaking Thus? Some Questions about Documentary Photography”, 1997, pp. 171.

[64] Sekula, “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)”, 2016, p. 60.

[65] “At that time a significant part – but by no means all – of my work was intended to bypass art world means of exhibition and dissemination; as a result, much of it took the form of postcard works and videotapes also circulated by post.” Rosler, “afterword: a history”, 2006, p. 94.

[66] Buchloh, “Conversation with Martha Rosler”, 1998, p. 27. On Rosler’s position on conceptual art see also ibid., pp. 33 ff. On her criticisms of aestheticisation discourses, which she believes overlay the political and critical potential of photography, see also Martha Rosler, “Notes on Quotes”, in: Rosler, Decoys and Disruptions. Selected Writings, 2004, pp. 133–148.

[67] Rosler, “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)”, 2006, p. 84.

[68] Ibid.

[69] Ibid., p. 81.

[70] Ibid., p. 82.

[71] See also Rosler’s own statement in her interview with Benjamin Buchloh: “But from its inception I felt that The Bowery was a work for art galleries and museums. […] It was meant as an art work, hanging on the wall – why else would I bother calling it ‘inadequate’? Who cares about inadequacy of representation? The general public doesn’t care about inadequacy, the art world and artists care about adequacy of representational systems. The title showed that whatever other people might make of the work, its primary audience was the person interested in the production of meaning through art or language, or poetry.” Buchloh, “Conversation with Martha Rosler”, 1998, p. 45.

[72] Rosler, “afterword: a history”, p. 96.

[73] Rosler, “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)”, 2006, p. 81.

[74] Ibid., p. 82.

[75] “Martha Rosler in Conversation with Molly Nesbit and Hans Ulrich Obrist”, 2005, p. 24. On the quote function of the images see also Rosler, “Notes on Quotes”, 2004. “The photographs confront the shops squarely, and they supply familiar urban reports. They are not reality newly viewed. They are not reports from a frontier, messages from a voyage of discovery or self-discovery. There is nothing new attempted in a photographic style that was constructed in the 1930s when the message itself was newly understood, differently embedded. I am quoting words and images both.” Rosler, “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)”, 2006, p. 87 (emphasis in original); see also Rosler, “afterword: a history”, 2006, p. 97.

[76] “A direct hommage is visible in one of my Bowery photographs: I was very struck by a picture Evans had taken of a store front with a bunch of hats piled up against a window. It seemed like a Bohemian inversion of the received discourse of the urban: for him the street was the safe and known place, and the shop interior is presented as a glimmering shadow, a semi-dangerous, unknown space. That’s what I think that photo is about – the essential unknowability or undisclosability of this interior space.” Buchloh, “Conversation with Martha Rosler”, 1998, p. 38.

[77] Rosler herself addresses the question of aesthetics: “A problem with trying to make such a notion workable within actual photographic practice is that it seems to ignore the mutability of ideas of aesthetic rightness. That is, it seems to ignore the fact that historical interests, not transcendental verities, govern whether any particular form is seen as adequately revealing its meanings – and that you cannot second-guess history […].” Rosler, “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)”, 2006, p. 82.

[78] Sekula and Buchloh, “Conversation”, 2003, p. 37.

[79] Buchloh, “Conversation with Martha Rosler”, 1998, p. 51.

[80] Sekula, “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)”, 2016, p. 58.

[81] Sekula and Buchloh, “Conversation”, 2003, p. 41.

[82] Barthes, “Semantics of the Object”, 1988, p. 182.

[83] Mitchell, “Beyond Comparison: Picture, Text, and Method”, 1994, p. 91.

[84] A selection of the House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home montages, which were created between 1967 and 1972, can be found in: Rosler, irrespective, 2018.

[85] Sekula, “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)”, 2016, pp. 56 f.

[86] Rosler’s texts “in, around, and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)” (1981) and “afterword: a history” (2006) were both published in the book medium in Martha Rosler, 3 works, 2006, together with The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems.