Literature and Photography: From Text to Photo, from Photo to Text

by Silvia Albertazzi, translated by Georgia Grey

The Photocaptionist is delighted to present for the first time in English an excerpt of Silvia Albertazzi’s book Literature and Photography, published by Carocci editore in 2017. We selected the first section of chapter 4, entitled ‘From Text to Photo, from Photo to Text’.

Enjoy the photo-literary feast!

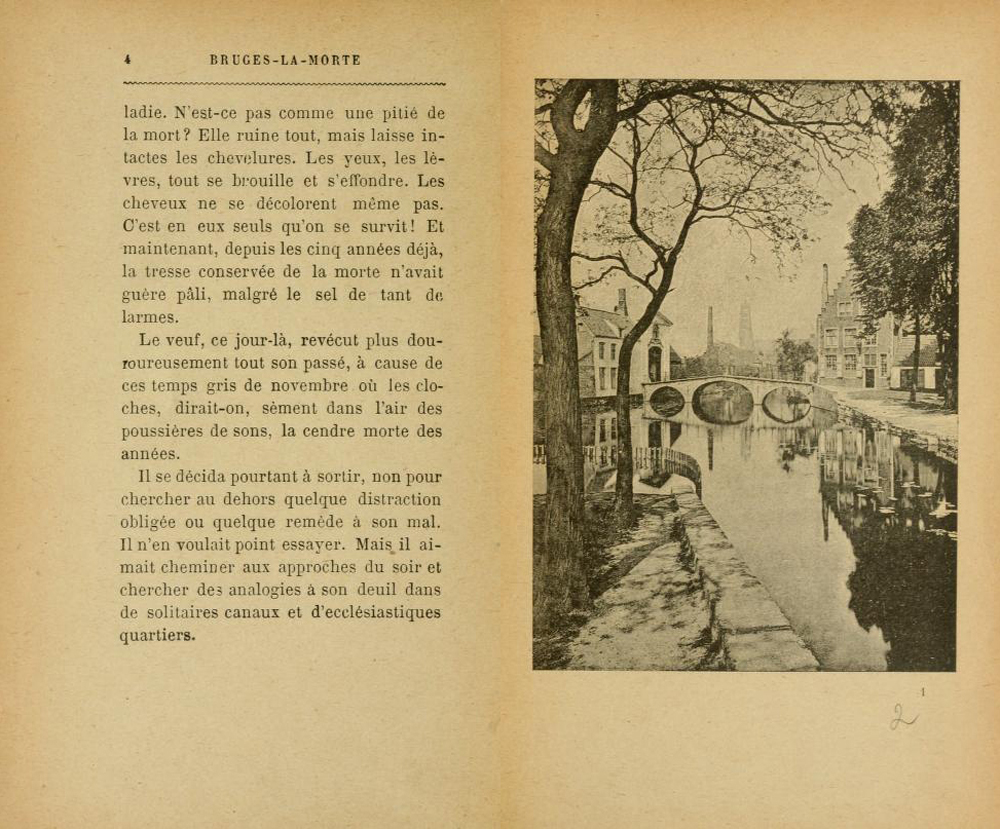

It is customary to indicate Bruges-la-Morte (1892) by Georges Rodenbach as the first example of a finished illustrated novel. In fact, although there had previously been narrative works accompanied by photographs (for example The Marble Faun by Hawthorne and Romola by George Eliot, published respectively in 1860 and 1863 by Tauchinitz, and accompanied by lavish photographic spreads) it should be noted that only with Rodenbach are photographs and text conceived of simultaneously, considered equally necessary by the author. Nevertheless, while the first edition of the novel was illustrated with coeval views of Bruges, in the following editions the photos were either substituted by drawings or omitted altogether, thus emphasising the difficulty in accepting photography as artistically complementary to written text. The only English translation even substituted them with more contemporary images, disregarding the importance of the interchange sought after by the author between his text and those particular photos.

Bruges-la-Morte, considered today as the precursor to a whole set of literary photo texts – from Nadja (1928) by Breton to Vertigo (1990) by Sebald and Istanbul (2003) by Pamuk – places next to the story of a man who wanders aimlessly around a spectral city, torn apart by the death of his wife, thirty-five photographs that represent as many views of the locations he crosses or that dwell in his memory. The city thus appears as a ghostly place, whose fluctuating shades of grey contribute to the creation of a disquieting atmosphere. Protagonist of the story as well as representation of the missing wife, Bruges is seen through the eyes of the desperate husband. The photos allow the reader to adopt the perspective of a man for whom the city has become a desert, its streets epitomising the missing presence of his beloved. In the photographs there are few human figures, and if so they are captured from a distance and blurred, also due to the long exposure time necessary for obtaining a satisfactory image during Rodenbach’s time. If in the text the locations are filtered through the eyes as well as the memory of the protagonist, that very same city, depicted in all shades of grey and black, seems to be described by a series of photographs rather than direct experience, as if Rodenbach, aside from choosing the images to accompany his text, is also using them to tell his own story of Bruges (Elkins 2014).

From Bruges-la-Morte, by Georges Rodenbach, Paris 1892.

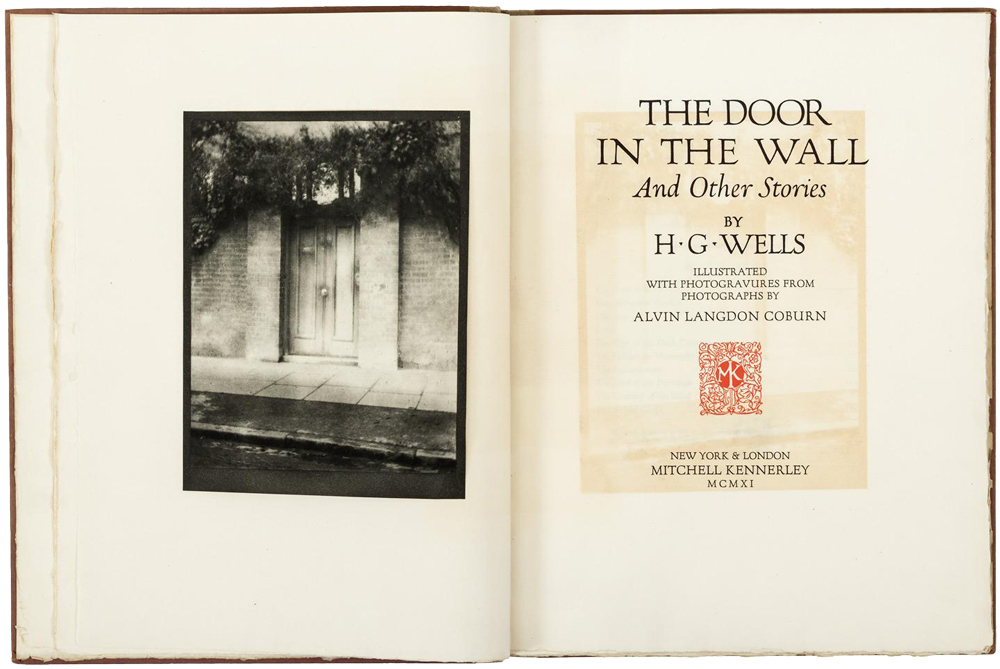

Different is the case of H.G. Wells, who, in 1908, invited the American Alvin Langdon Coburn, at the time considered ‘the greatest photographer in the world’ as stated by George Bernard Shaw, to illustrate those short stories that he believed to be most suitable for photographic rendering. Together, writer and photographer selected eight short stories that were published in 1911 under the title The Door in the Wall and Other Stories, accompanied by ten photographic engravings by Coburn. Coburn, a student of Steichen and a favourite of Stieglitz, as well as a follower of photographic pictorialism, underlines in his renderings the strong fantastical component in Wells’ stories; his game of lights and shadows make the landscapes even more mysterious and unsettling, soliciting from the observer an emotional response analogous to that of the text. Coburn replaces the detail and precision of the realistic image with refined photographic effects, blurred lines that are reminiscent of English paintings of the time, in particular the urban gaslit landscapes by John Atkinson Grimshaw. Thus, the uneasiness that winds its way into Wells’ stories finds the perfect representation in his mysterious images.

From The Door and the Wall and Other Stories, by H.G. Wells, New York 1911.

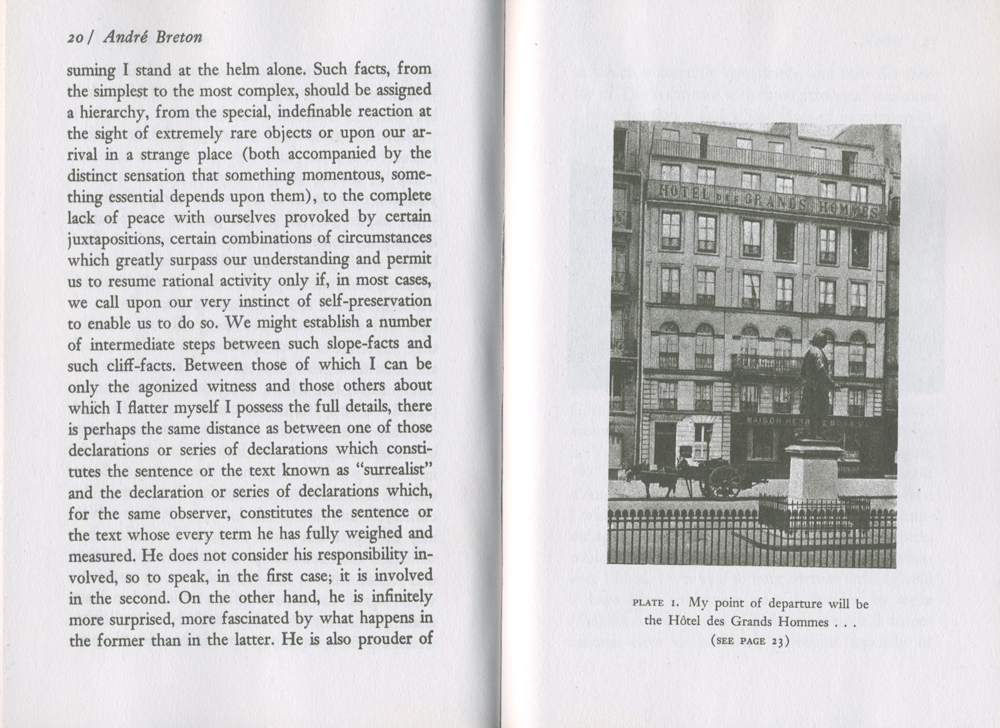

Closer to Rodenbach and far from the mysterious atmospheres of Wells and Coburn is André Breton, who in 1928 published Nadja, a work in which photographs are primarily used for documentary purposes and serve as a counterbalance to the enigmas of the text, appearing, in the words of the author, as a veritable ‘anti-literary mystery’. If Wells and Rodenbach both choose decisively artistic images, Breton favours their documentary aspect, albeit understood in the Surrealist sense as bearer of an unsolvable mystery: the photographs of locations by Jacques-André Boiffard that appear in the text are deliberately banal, flat, and, according to the author, have the primary purpose of replacing descriptions (or rather, eliminating them). Moreover, in this work Breton develops his notion of enigma, the unexplainable object or event which consequently to its ‘convulsive beauty’ prevents the protraction of everyday activities, of the ordinary ensnaring bourgeois life.

Thus the enigmas in the story are in contrast with the banality of the photos, Boiffard’s ones as well as the anonymous images found by Breton in commercial agencies or museums, and also the portraits by Henri Manuel; the only photographs noteworthy of recognition are a couple of portraits signed by Man Ray. The photos do not contain clues that help clarify our reading of the text, nor do they contain symbolic or allegorical elements. If anything, they represent an ante-litteram contribution to the psychogeography of daily life, where the lack of artistic elements is intended as confirmation of authenticity. Prose and image thus contradict each other: the empty and indifferent streets host a mysterious and passionate love story; the verbal images are evocative and enigmatic; the intentionally flat and banal photographs incapable of grasping the ‘convulsive beauty’ experienced by the narrator. And yet, perhaps it is precisely this contrast between the photos’ anonymity and the unique development of the story that renders Nadja (Elkins 2013) a truly surrealist work.

From Nadja, by André Breton, London 1999.

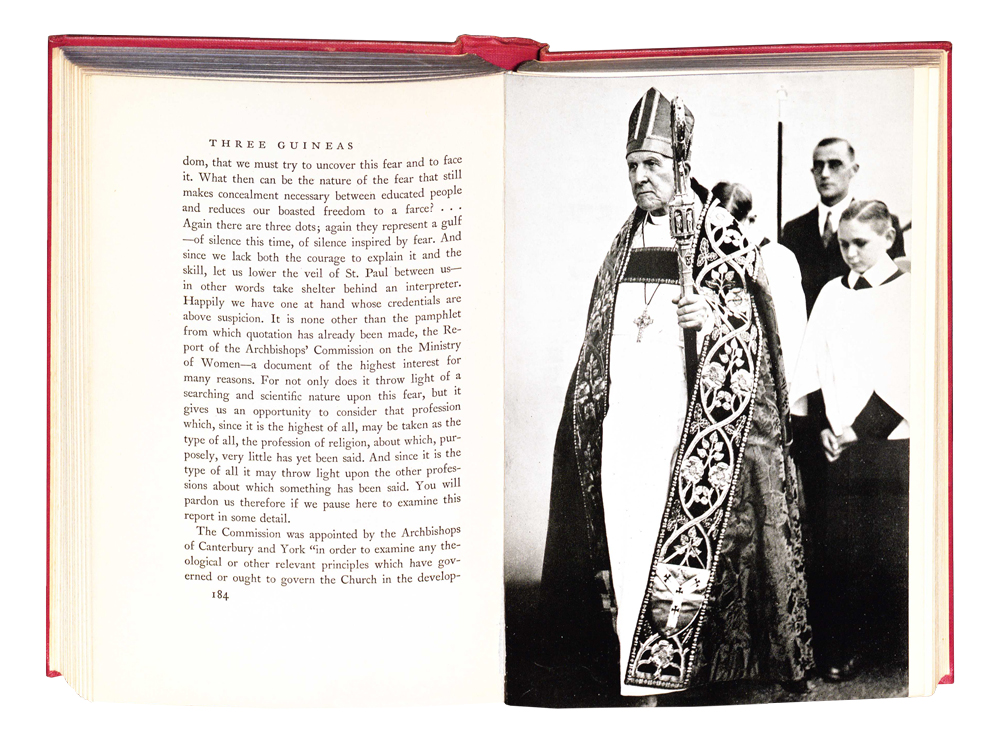

Ten years after Breton’s book, Virginia Woolf’s anti-war essay Three Guineas was published in Great Britain, complemented by five photographs that will disappear in subsequent editions. These are images of patriarchal power – a general, a bishop, soldiers, judges, academics – dressed in their respective emblems of status. Woolf denounces, like the child in Andersen’s fairytale, the obscene nudity concealed under the empty formal wear. Fixed in their rigid poses, the subjects of the photographs depict the immobile and corporate nature which characterise the clans in power discussed in the text, reiterating the inability to separate patriarchy from fascism (Zaccaria 2008, p. 36). Without publishing them, Woolf is referencing another set of photos, related to the horrors of the Spanish war, allowing the reader to visualise them in their own mind and consequently create their own counter-narrative, in open contrast to all that the figures of power represent. The result is a pamphlet where the conceptualisation of photography becomes ‘hermeneutic of fascism and the patriarchy’ (ivi, p. 47): it is up to the reader to extract meaning from the printed images and, above all, create a mental commentary about the images that are not present, thanks to their written representation and the reader’s awareness of similar images from the newspapers of the time.

From Three Guineas, by Virginia Woolf, London 1938.

If Virginia Woolf relied on the circulation of images from the Spanish massacre to create an empathic relation with her readers and solicit anti-fascist and anti-military awareness, other novelists have used artistic photographs for purely narrative purposes, without publishing them, sure of the fact that the popularity of those images would instantly bring the subject to the reader’s mind. This is the case of Richard Powers, who, in 1985 published, Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, a novel that imagines the fate of the three young men depicted in August Sander’s photograph by the same name (c. 1914), and Philippe Delerm who in Les Amoureux de l’Hôtel de Ville (1993) tells the story of the two lovers depicted in the extremely famous photo by Robert Doisneau, Le Baiser de l’Hôtel de Ville (1950). Although both authors take inspiration from famous photographs, the narratives they develop differ: Powers entwines the story of the three farmers tragically overcome by the First World War with the vicissitudes of two late-twentiethth-century Americans, a digital magazine editor and a narrator obsessed by photography, who inserts in the storyline reflections and ideas on the photographic medium in the form of academic essays. Delerm, much more simply, imagines the disintegration of the love story immortalised by Doisneau from the point of view of an innocent victim: the son of the couple. In both cases, the authors envisage what happened after the photograph was taken. Yet, if Delerm limits himself to the future of the subjects in the photograph, Powers pushes his own narrative reflection on imagining the future of the photographic device, considering the developments and progress that this technology assured to the carnage of the First World War as well as to photographic perfection and the diffusion of photography as a widely distributed art form.

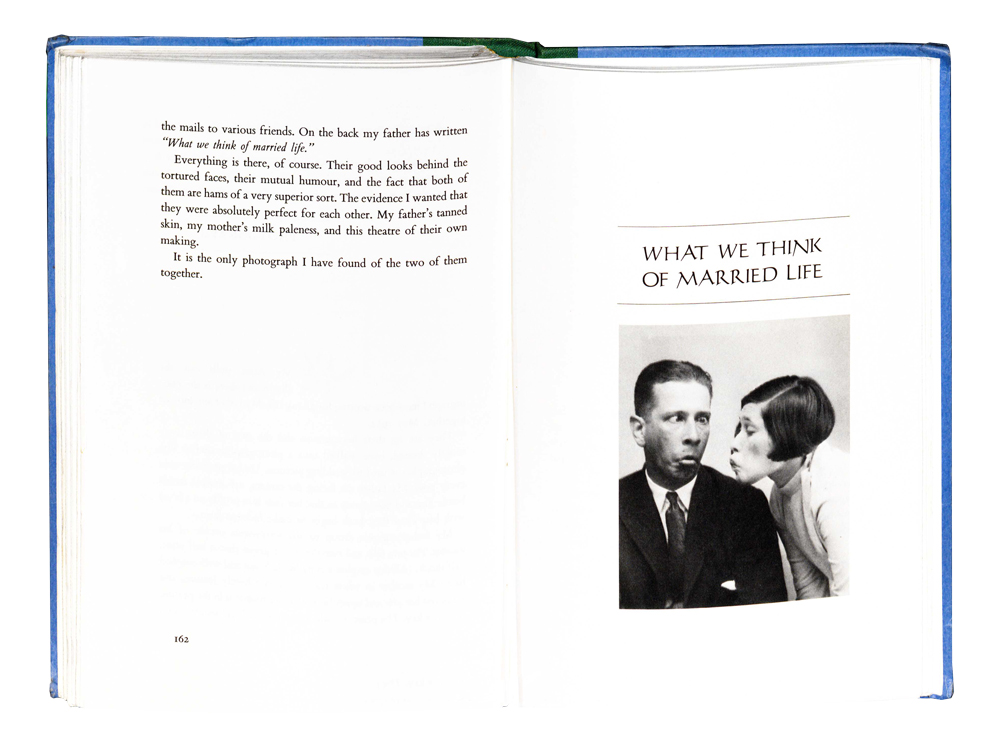

The novel Coming Through Slaughter by Michael Ondaatje also takes inspiration from a photograph placed on the title page, while Paul Auster’s research, conjectures, and meditations in the first part of The Invention of Solitude are inspired by two photographs, both printed in the book. Photographs also appear in other works by Ondaatje: in his memoir Running in the Family from 1982 a photo of his parents pulling faces translates their opinion on marriage into image form, suggesting both the atypical nature of the relationship and also the difficulties of a relationship built on similar premises. In The Collected Works of Billy the Kid from 1970, vintage photographs – snapshots, portraits and photographs of interiors, all equally marked by time and for this reason not easy to decipher, some of which are the work of the famous photographer of Western scenes, Laton A. Hufman – punctuate the story of the most famous bandit of the West and the ‘left-handed poems’ of Ondaatje. However, it is not those blurred, badly framed, grainy images, in all shades of black and grey, that illustrate the story (or provide a counter-narrative); it is ‘photography’ itself that does so, starting from the book opening: an empty, white rectangle, which according to the caption is the photograph of Billy, ‘made with the Perry shutter as quick as it can be worked’ (Ondaatje 1995, p. 19).

From Running in the Family, by MIchael Ondaatje, London 1983.

Authentic anti-narration, the inexistent photo, complete void, extremely white where white is lacking in all other images in the book, appears to be both a sign of the impossibility of capturing a portrait of Billy, freezing his image, while also calling into question the means of photography which, far from stopping time, if they seek to reproduce its flow, can only reach a meaningless absence of motion. Coincidentally the caption proceeds to reference photographic experiments on fast-moving objects ‘with the lens wide open (…) many of the best exposed when my horse was in motion’. As with Powers, the discussion that started from photography becomes a discussion on photography, its limits and its documentary value; like in Three Guineas, where it is the reader who structures and formulates this argument. The photo / non-photo that opens Ondaatje’s work brings to mind the photographic ‘Verifiche’ (Verifications) carried out by Ugo Mulas during that same period, experiments aimed at understanding the habitual actions of photographers, detached from their utilitarian traits. Mulas’ verification n. 11, L’ottica e lo spazio, ad A. Pomodoro (Optics and Space, to A. Pomodoro), is also a blank page, and if the white rectangle that opens the work of Ondaatje supposedly depicts an image too fast to be fixed on paper, that of Mulas is an un-taken photograph, whose absence is thus justified by the photographer: ‘as the focal length of the lens increases, the things around it, that gave it a setting, a size, slowly disappear, with the result that the subject, estranged from time and space, becomes almost mythical, idealized’ (Mulas 1973, p. 176). Mythical, idealised, impossible to photograph: just like Billy, alienated, almost deleted from his context by a fast-moving shutter.

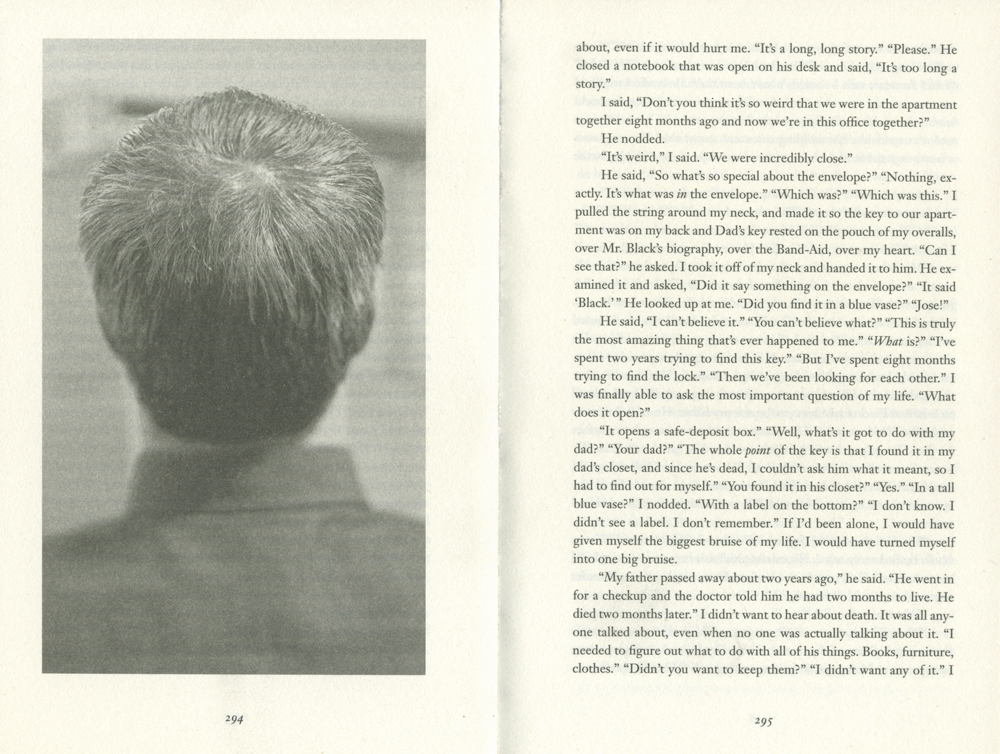

From Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close, by Jonathan Safran Foer, London 2006.

The refusal of the ‘fugitive moment’ that characterises Mulas’ approach seems to distinguish the iconographic choices of authors of some of the most interesting narrative texts accompanied by photographs from the last decades. The photographs printed in novels such as Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (2005) by Jonathan Safran Foer or 20 Fragments of a Ravenous Youth (2008) by Xiaolu Guo stand out for their blandness. To reiterate the words of Mulas, writers could claim to have chosen them as proof of their conviction that ‘all moments are fugitive, and in a certain sense they are all of the same value, in fact, the least significant moment is perhaps the most exceptional’ (p. 146). Thus in Foer the flawed black-and-white photos, blurry and badly framed, which punctuate the text from which they derive their meaning, at the same time accentuate it, in a way that is not always easy to decipher. Banal images of birds in flight, people photographed from the back, details of household items – these are not mere illustrations, as often they appear to be disconnected from the narration and decontextualised. Similar to the visual rendering of a postmodern list of objects, it is only at the end of the novel that the photos take on a highly symbolic meaning. The reader understands that some of the images which were seemingly hard to decode but have insistently been placed before their eyes are the shocking photos of those trapped inside the Twin Towers in New York, who threw themselves from the building to escape the explosion on September 11th 2001. Collected in a photographic appendix at the end of the book, they create a sort of flip-book, which, when consulted, gives the illusion of a backward movement which sees the bodies passing from the act of falling to that of jumping into the abyss. It is up to the reader to interpret this backward movement as a sign of hope, or rather, as the bleak representation of a fantasy typical of traumatised people, the idea of being able to rewind time, until the point just before the fatal moment is reached, thus altering history (Albertazzi 2012).

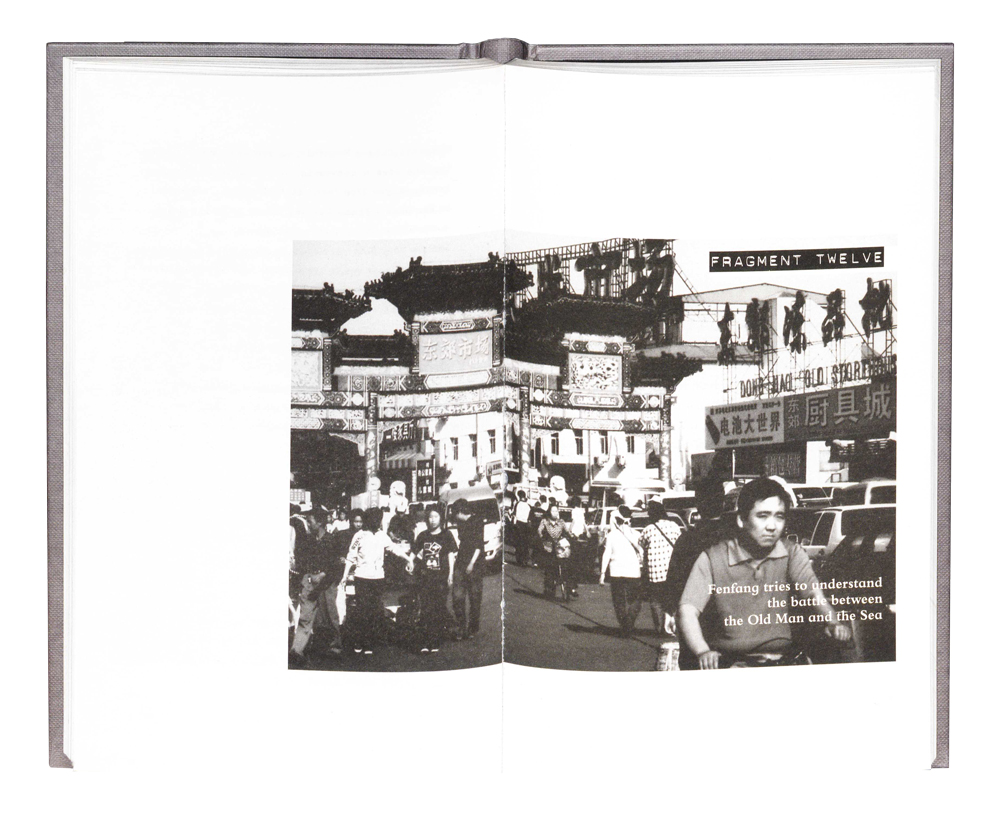

From 20 Fragments of a Ravenous Youth, by Xiaolu Guo, London 2008.

Regarding Guo, instead, the twenty photographs at the beginning of his twenty fragments are mainly images of everyday life and banal Chinese landscapes, of no particular tourist interest and at times decidedly squalid, seemingly freed from the fragmented content that they aim to illustrate. Here, even more than in Foer, it becomes apparent how in novels that contain photographic material, photography, rather than becoming an illustration or anti-illustration, takes on the role of ‘oblique illustration, or, more precisely, doubt’ (Baetens, Van Gelder 2006, p. 265, authors’ italics). It is not a question of placing text and photos in direct relation to one another based upon a logic of identity, (or a relationship based on common reference), but rather of introducing a logic of location, based upon the space that text and photos share on the page, mixing representation and thus disregarding the stereotypical expectations of the reader (p. 266). According to Mulas, it is the same for the photographer (1973, p. 146), ‘what really matters is not so much the privileged moment, it is identifying one’s reality, after which all moments are more or less equal’. Coincidentally, in response to those who asked for a justification of his choice to print photographs in his novel, Foer replied:

‘It was not a conscious decision, arising from some theory or critical idea. It reflects the situation in which I was in from an aesthetic point of view […] I didn’t set out to create something experimental, it didn’t interest me to play with form: that was the form taken by my imagination during that time and I chose not to question it. (Foer in Albertazzi 2016, p. 5).

Hence photography as an imaginative form, a form so ingrained in individuals that it manifests itself on an unconscious level; confirming the validity and contemporaneity of Susan Sontag’s assertion: ‘Now all art aspires to the condition of photography’ (1978, p. 130).

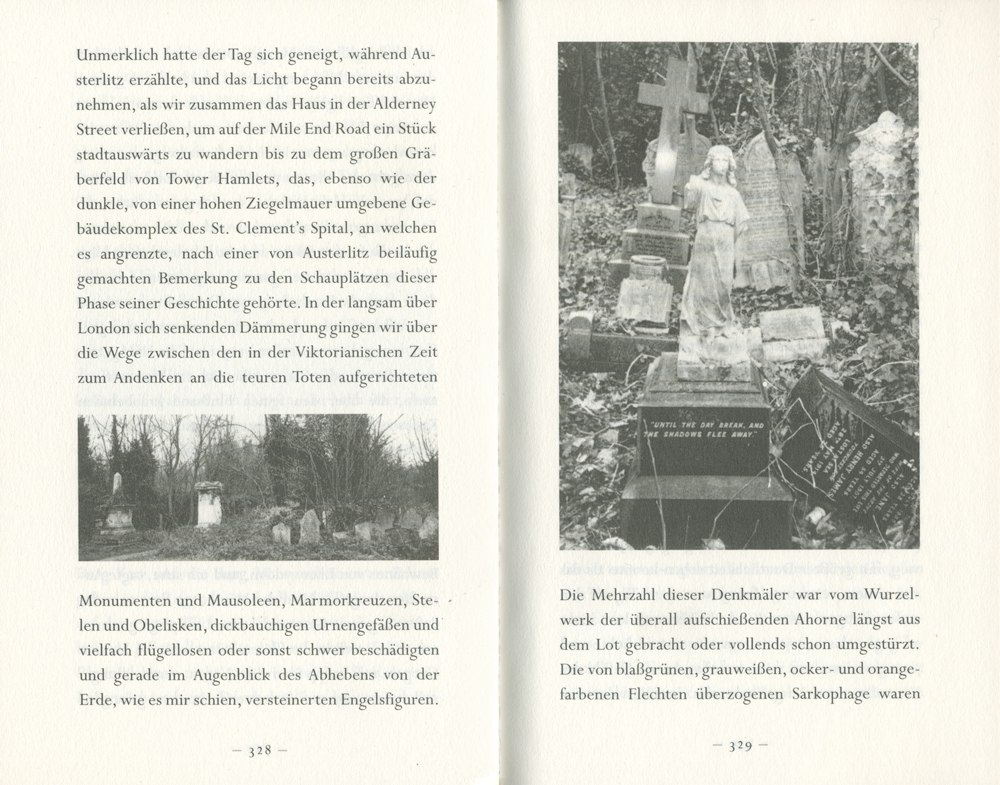

From Austerlitz, by W.G. Sebald, Frankfurt am Main 2003.

‘Doubtful’ illustration, photography amplifies the narrative crossover between fiction and truth. In a novel like Austerlitz by Winfried G. Sebald from 2001, the photographs help create a temporal coexistence between the living and the dead, real and fictitious characters, Big and private stories, reaching a sort of ‘infinite now’, the ‘transparent time’ of photography (Jussim 1989, p. 53). Much more prosaically, William Boyd’s Sweet Caress from 2015 involves the readers in a narrative game in which the photographs – real and printed within the text – have the function of confirming the truthfulness of the story – which is completely fictitious – of a photographer whose work spans the twentieth Century, from 1930s Berlin to the Vietnam War. The documentary use of photography is openly renounced here: the images printed in the text, which are passed off as having been taken by the lead character or from her family album, in truth are from the author’s vast collection of vintage snapshots. In other words, these are ‘found’ photographs: so anonymous that Boyd admitted to hoping that one of his readers would find themselves in them or recognise one of the subjects. And yet, at least initially, the impact on truth is noteworthy; those who approach the book without knowing its background are led to believe that they are reading the real biography of a photographer who actually existed. Accordingly, the photographs appear as mere illustrations: often an ekphrasis is given earlier, which only confirms their representation. Thus, although the novel’s structure is somewhat analogous, in The Rain Before it Falls by Jonathan Coe, the absence of the photographs described in the text by the elderly lady, allows the reader to imagine events and locations, thus amplifying the fictitious element of the story. By contrast, in Sweet Caress, the presence of the photos, which should confirm the veracity of the story, ends up creating more doubt on their authenticity. Fashioning a fictitious story out of real photographs, Boyd, just as he seems to be relying on them, annuls the referential component inherent to photography, which thus remains an artifact, an objet trouvé. ‘Photography […] seems to want to talk on its own, but it doesn’t know how’, stated Nino Migliori. ‘Only men, who have language, can be believed or not’ (Migliori in Smargiassi 2013, p. 23). Emphasizing the ambiguity of the photographic medium as much as the literary narrative, Boyd proposes a novel in which the fictional narrator makes the photographs ‘speak’ and is believable, but the author who allows the narrator ‘to speak’ isn’t. Only the complicity of the audience can guarantee him that particular form of ‘believability’ reserved for fictional stories.

Silvia Albertazzi is Full Professor of Postcolonial Studies and History of the English Culture at the University of Bologna. She is the author of the first Italian book on Postcolonial Theory, Lo sguardo dell’Altro (The regard of the Other, Carocci, Rome, 2000), updated and reissued in 2013 with the title La letteratura postcoloniale. Dall’Impero alla World Literature (Postcolonial Literature. From the Empire to World Literature). She has published two volumes on literature and photography, Il nulla, quasi. Foto di famiglia e istantanee amatoriali nella letteratura contemporanea (Nothingness, Almost. Family photographs and Amateur Snapshots in Contemporary Literature, Firenze, Le Lettere, 2010), and Letteratura e fotografia (Literature and Photography, Carocci, Rome, 2017), and co-edited with Ferdinando Amigoni a collection of essays, Guardare oltre: letteratura, fotografia e altri territori (Looking Beyond: Literature, Photography and Other territories, Meltemi, Rome, 2008). She is a book reviewer for Alias, the literary supplement of the newspaper il manifesto.

Bibliography

Silvia Albertazzi, Belli e perdenti. Antieroi e post-eroi nella narrativa contemporanea di lingua inglese (Beautiful and Losers. Antiheroes and Post-heroes in English Language Contemporary Fiction), Armando Editore, Rome, 2012.

Silvia Albertazzi, ‘Figli, amici, amanti e altri generi impossibili’ (‘Sons, Friends, Lovers and Other Impossible Genres), ‘Alias’, il manifesto, 04 September 2016, p. 5.

Jan Baetens and Hilde Van Gelder, ‘Petite poétique de la photographie mise en roman (1970-1990)’ [‘Little Poetics of Photography mise en novel (1970-1990)’] in Danièle Méaux, éd., Photographie et romanesque (Photography and the Novelistic), Lettres Modernes Minard, Caen 2006, pp. 257–71.

James Elkins, Writing with Images: 4/ 2/ André Breton, Nadja, 2013, available here, accessed 20 October 2016.

James Elkins, Writing with Images: 3/1/ Georges Rodenbach, Bruges-la-Morte, 2014, available here, accessed 20 October 2016.

Estelle Jussim, The Eternal Moment: Essays on the Photographic Image, Aperture, New York 1989.

Ugo Mulas, La fotografia (Photography), Einaudi, Turin, 1973.

Michael Ondaatje, Le opere complete di Billy the Kid (The collected works of Billy the Kid), Theoria, Rome/Naples 1995.

Michele Smargiassi, ‘Per volontà, con e contro il caso. Intervista a Nino Migliori’ (‘For will, with and against chance. Interview with Nino Migliori’), in Nino Migliori. La materia dei sogni (Nino Migliori: The matter of dreams), Maison européenne de la photographie, Paris, 2013, pp.15–23.

Susan Sontag, Sulla fotografia (On Photography), Einaudi, Turin 1978.

Paola Zaccaria, ‘Nero su bianco: narrazione e fotografia nella (contro) sfera pubblica’ [‘Black on White: Narrative and Photography in (against) the public sphere], in Silvia Albertazzi and Ferdinando Amigoni, Guardare oltre: letteratura, fotografia e altri territori (Looking Beyond: Literature, Photography and Other territories), Meltemi, Rome, 2008, pp. 31–49.

Translated from Italian by Georgia Grey. Translation supported by David Solo.