Fondation Fiminco: Frictions by Luis Carlos Tovar

On the occasion of the exhibition Pleins Feux of the artists in residence at the Fondation Fiminco in Romainville, Paris our director Federica Chiocchetti collaborated with Colombian artist Luis Carlos Tovar by responding to his new body of work and installation Frictions with a text that we present here.

< >

For how long can an artist resist working with a disquieting archive, which is both private and public? How long does a piece of news last in our memory?

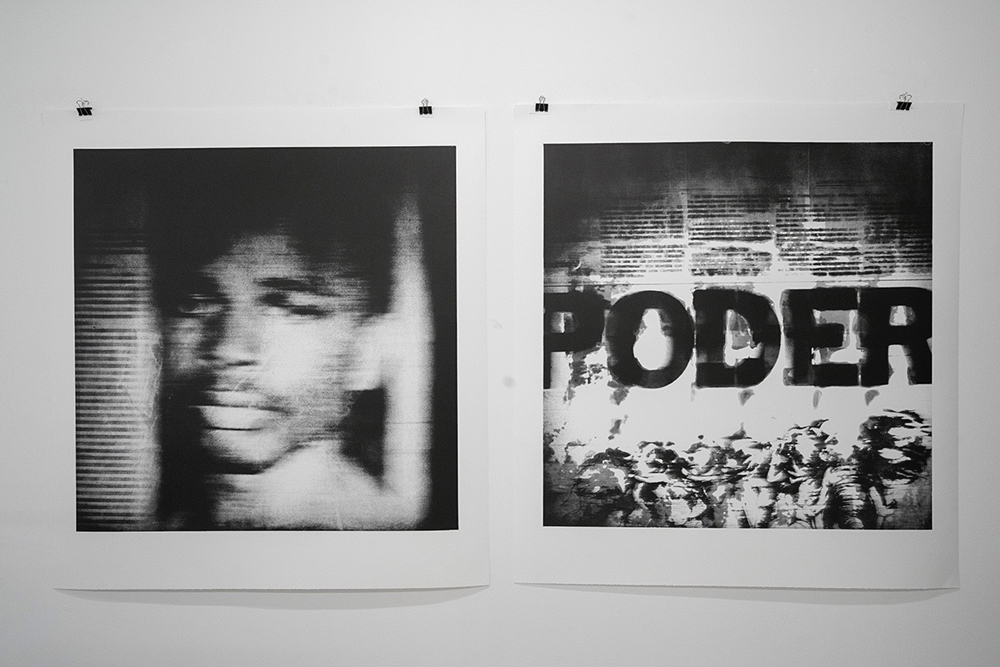

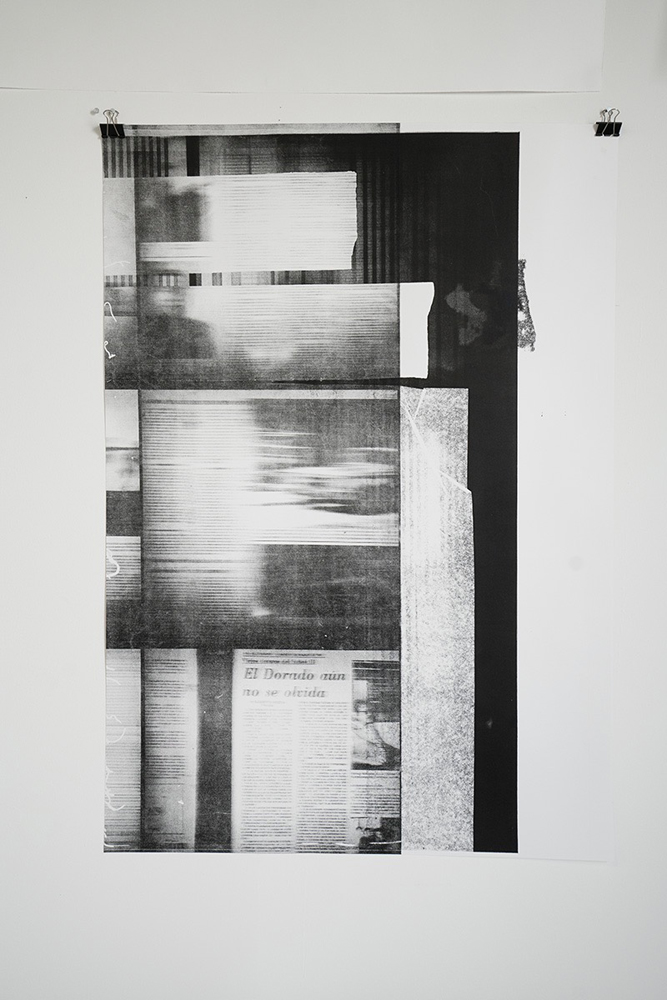

Tracing the missing parts of the press news that happened to appear in the proximity of those referring to the kidnapping of his father by the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) in 1980, in the clippings that his mother meticulously collected from the Colombian newspaper El Tiempo, Tovar has created a new accidental archive that he somewhat unconsciously finds himself frictioning away.

Or perhaps not so unconsciously.

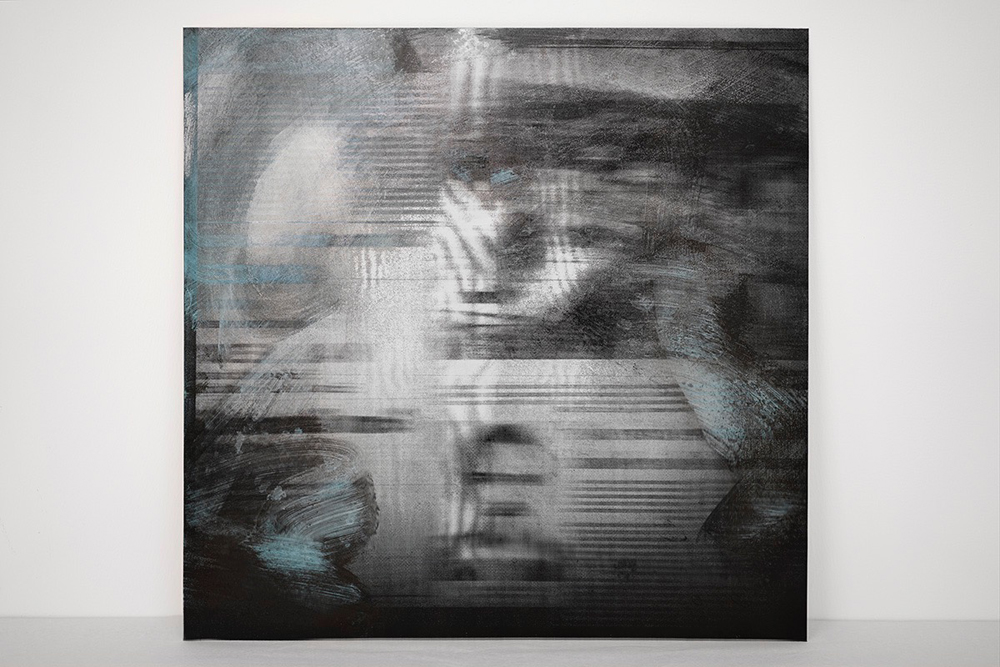

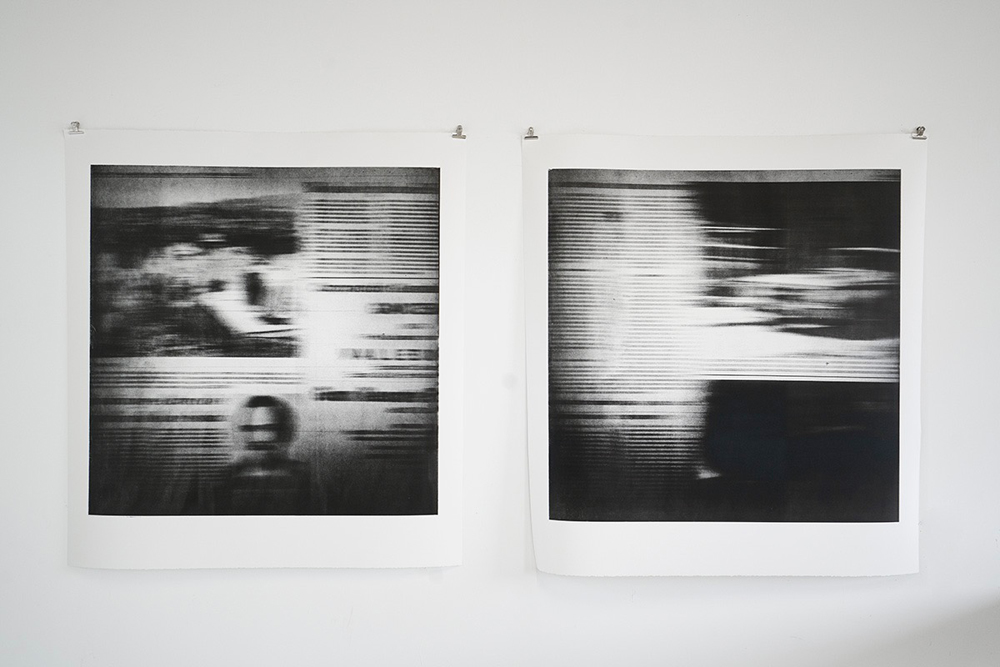

Fascinated by the fleeting experience of consulting the newspaper’s archives through their only existing support as microfilms, and keen to experiment with old lithographic and photoengraving techniques, no longer in use in the newspaper industry, Tovar captures and reproduces the physical and symbolic fading away of these pieces of peripheral news, in which words and images melt to leave us in a state of inquisitive contemplation. Shrouded in a halo of loss these disappearing fragments of scripto-visual news of Colombian violence and folklore that Tovar selected from his peripheral and accidental archive, echo the mystery behind the unpredictable and whimsical mechanics of memory. Memory can indeed be completely disconnected from ethics.

There are a number of intriguing elements that make Frictions a coherent continuation of Jardin de mi padre, Tovar’s artist book that dealt more directly with the kidnapping of his father. [1]

First, Tovar has the natural inclination of creating a fascinating dialogue between his practice and the history of photography and its processes. The collective and therapeutic making of cyanotypes with members of the artist’s family in Jardin de mi padre echoes his father’s habit of collecting and inserting butterflies and plants in the pages of the communist books he was forced to read during his captivity, organically connecting with Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes of British Algae, the very first book of photographs ever made. [2]

The struggle to fix an image has been the main preoccupation for all the inventors of the photographic medium, from Nicéphore Niépce to Hippolyte Bayard, Louis Daguerre and William Fox Talbot, who, more or less successfully, fought against the fading of appearances. [3] Frictions subverts these photo-pioneers’ obsession with fixing the image by pushing to the extremes Walter Benjamin’s idea of the mechanical reproduction of the work of art and forcing Tovar’s accidental press archive to fade away by its repeated reproducibility. [4]

Second, on a more personal level, perhaps there is a subtle connection between inducing the fading of the words and images of the accidental and tangential press archive that constitutes Frictions and the missing Polaroid the guerrilla fighters sent to Tovar’s family, as a proof that his father was still alive. The image was never found by the artist and acquired the aura of haunting invisibility that prompted him to investigate the family archive. Two other elements of Tovar’s family history could have unconsciously inspired the process of Frictions. The consequences of his father’s kidnapping on his body, namely the chronic kidney disease as a result of being kept in the extremely dark jungle environment of the Amazon and the ultraviolet B photo-therapy the artist’s father had to follow, to detox his poisoned blood and erase the marks on his skin. Also, his father’s impossibility to write a single word about the crime he went through, despite the recurrent exhortation from the artist for over ten years.

Departing from the Amazon, from the impact of nature, especially humidity, on photographic archives and from the attempt to symbolically apply ‘acupuncture’ to war in Colombia in his previous work, Tovar finds himself dematerialising press news through obsolete printing techniques to ephemerize even further the fragile layers of memory, which emerges as a hopeless battlefield in the extremely complex and brutal violence that still permeates Colombia since the 1940s. [5] ‘‘Colombia has a very thin layer of memory,’’ says artist Juan Manuel Echavarría, for whom the importance of remembering is a responsibility and a recurrent theme in his work, ‘‘nations can also suffer from Alzheimer’s’’. [6]

With Frictions, by thinning to the extremes Colombia’s layer of memory, Tovar appears more oriented towards the ‘pedagogy of oblivion’, for which forgetting is a mechanism to become aware of time, a notion he already explored when he took part in Cristina Lleras Ephemeral Museum of Forgetting. [7] ‘‘We all know that learning and memory are intimately connected,’ says Lleras, ‘we can understand some things better if we forget others […] it’s vitally important that we understand what we need to forget, or what we can forget’’. [8]

Lurking behind an only apparently conceptual work we find Tovar’s political and existential struggle to reconcile with a troubling past and a very discouraging socio-political present. [9]

Tovar’s work falls within the tradition of Latin American political art compellingly narrated by Luis Camnitzer in his essay ‘Imagination Redirected: Photography and Text in Latin America 1960-2013’; a tradition that, through words and images and often inspired by the press, explores the relationship between violence, trauma, memory and reparation. [10] Some artists, such as Antonio Manuel and Johanna Calle, have been more preoccupied with remembering and denouncing, while others, such as Oscar Muñoz and Luis Carlos Tovar, with forgetting and the life and death of images. [11]

In Colombia there is the war, a particular phenomenon in relation to memory. […] It’s as if we are living through an eternal present or in a past present… where people have no identities or particularities, where nobody remembers anyone else […]. In the collective mind, there is a misty mass, confused, contaminated, obscure, that is not…resolved. [12]

Deeply resonating with these words by Muñoz, Frictions offers Tovar an attempt towards another form of healing through the artistic process of archival dissolution, which, contrary to any logic, transforms annihilation into creation. As one picture is forgotten, so another is born. It is up to us if we want to see it misty, obscure and not…resolved, like Colombia’s history or uplifting and encouraging, like the current awakening of its civil society.

Federica Chiocchetti (PhD) is a writer, curator, editor and lecturer who explores the mysterious intersections of images and words through books, exhibitions, teaching and academic research, from the invention of the photographic medium to contemporary practices. Through her photo-literary platform Photocaptionist she collaborates with international institutions such as Jeu de Paume, Aperture and Fotomuseum Winterthur.

[1] Tovar, L.C. (2020). Jardin de mi padre. Barcelona and Lausanne: Editorial RM and Musée de l’Elysée.

[2] Lederman, R., Yatskevich, O. and Lang, M. (2018). How We See: Photobooks by Women. New York: 10×10 Photobooks

[3] Batchen, G. (2006). Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press and Roca, J. (2011). Oscar Muñoz: Protografias. Bogot : Museo de Arte del Banco de la Rep blica.

[4] Benjamin, W. (1969). The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In: Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books.

[5] LaRosa, M. and Mej a, G. (2017). Colombia: A Concise Contemporary History. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield; Uribe, M.V. (2005). Facing the Vacuity of Violence. In: Reuter, L., Juan Manuel Echavarría: Mouths of Ash. North Dakota Museum of Art: Charta and Brown, C. and Oldfield, P. (2007). Once More, With Feeling: Recent Photography from Colombia. London: The Photographers’ Gallery and Bradford: Impressions Gallery.

[6] Reuter, L. (2005). Juan Manuel Echavarría: Mouths of Ash. North Dakota Museum of Art: Charta

[7] Lleras, C. (2015). Museum of forgetting. The Bogot Post, August 7. Available from https://thebogotapost.com/museum-of-forgetting/7253/

[8] Lleras, C. (2015). Museum of forgetting. The Bogot Post, August 7. Available from https://thebogotapost.com/museum-of-forgetting/7253/

[9] Delorme, F. (2021). Épisode 4: De la Colombie au Pérou: le spectre de la guerre civile, in Amérique latine, le retour du refoulé. France Culture. Available from https://www.franceculture.fr/emissions/cultures-monde/ amerique-latine-le-retour-du-refoule-44-de-la-colombie-au-perou-lespectre- de-la-guerre-civile and Revuelta(s) – Un film de Fredi Casco et Renate Costa Perdomo (Fondation Cartier – 2013). Available from https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=EuBSM8uvoKI

[10] Camnitzer, L (2013). ‘Imagination Redirected: Photography and Text in Latin America 1960-2013’. In: Amêrica Latina 1960-2013: Photographs. Paris: Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain and Puebla, Mexico: Museo Amparo.

[11] Manuel, A. (1968), Flans; Calle, J. (2012). Pie de fotos; Muñoz, O. (1995). Aliento. See the catalogue of the Fondation Cartier’s exhibition Amêrica Latina 1960-2013: Photographs and Oscar Mu oz: Protografias.

[12] Muñoz, O. in Brown, C. and Oldfield, P. (2007). Once More, With Feeling: Recent Photography from Colombia. London: The Photographers’ Gallery and Bradford: Impressions Gallery, p. 13.