Julia Margaret Cameron, by Marta Weiss

15 Jun 2015

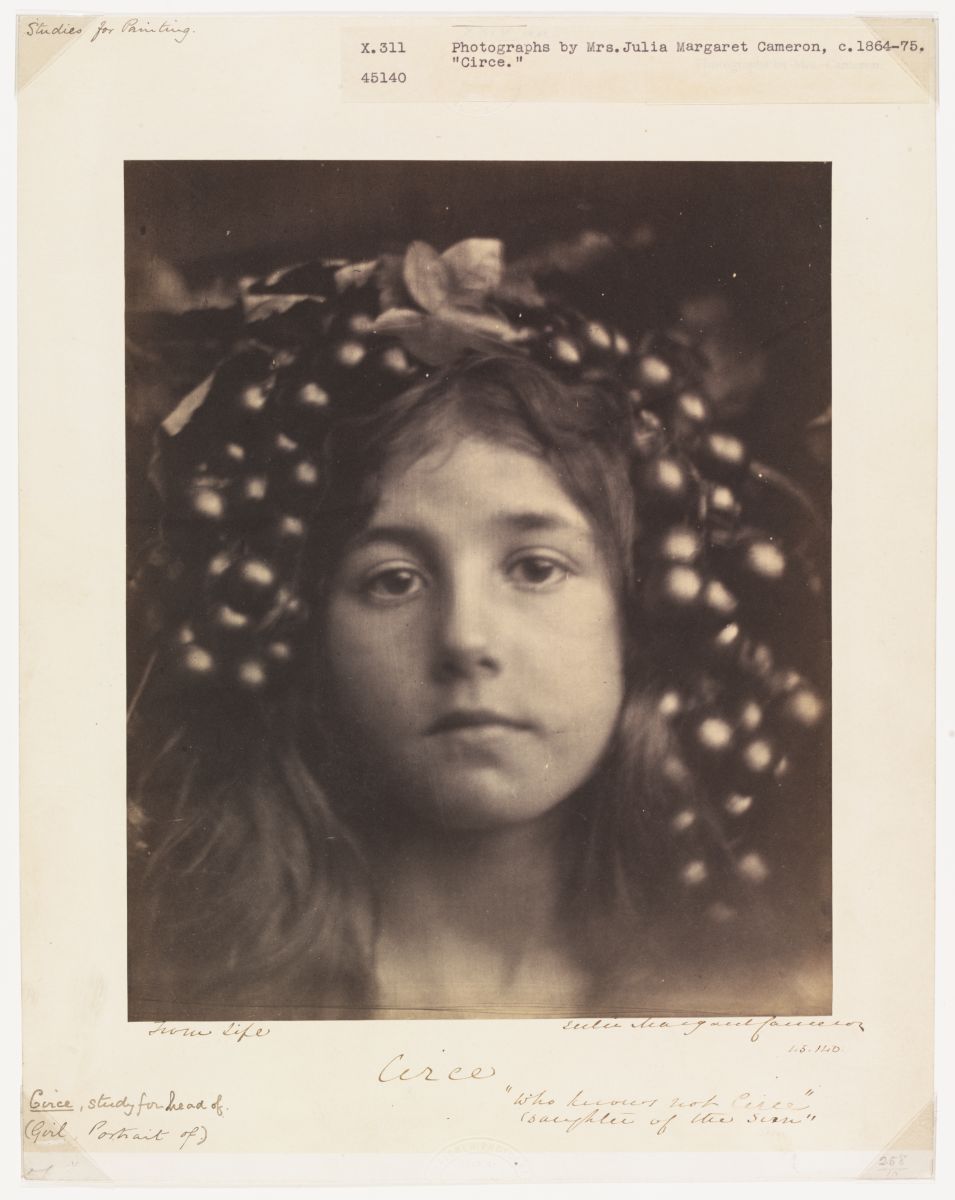

The mount of this photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron attests to its changing status over the course of its lifetime in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Cameron inscribed it ‘From Life’ and added her signature, title, and a quotation from Milton, ‘Who knows not Circe/daughter of the Sun’. Museum classifications were added later: ‘Studies for Painting’ in the upper left and ‘Circe, study for head of (Girl, Portrait of)’ in the lower left. Later still, a typed label classifying it by the artist’s name was pasted on.

‘Circe’ entered the collection in 1865, within months of its production. In May of that year, Cameron sent a portfolio to Henry Cole, the founding director of the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A), declaring, ‘I should be so proud & pleased if this complete series could go into the South Kensington Museum’. She had been making photographs for less than 18 months, having received her first camera as a gift in December 1863, at the age of 48. Cameron’s artistic ambitions were high and she had already established her main themes, which she described as ‘Portraits’, ‘Madonna groups’, and ‘Fancy Subjects for Pictorial Effect’. In June 1865, the South Kensington Museum purchased 63 of her photographs and in July and September acquired a further 51. It was the only institution in Cameron’s time to collect her photographs in any depth, and, in November 1865, became the only museum to exhibit her work in her lifetime.

The South Kensington Museum had been collecting photographs since its establishment in 1852. These were primarily record photographs of works of art and architecture that, in keeping with the museum’s educational mission, could serve as inspirational examples for artists and designers. Cameron, by contrast, conceived of her photographs as works of art in their own right. Cole apparently endorsed this view and mainly selected Cameron’s most self-consciously artistic subjects – Madonnas and Fancy Subjects – for acquisition. They were then, according to one contemporary critic, ‘awarded a prominent place at the South Kensington Museum close to the picture collections, where they [hung] “in their pride alone”’.

By exhibiting Cameron’s photographs in 1865, the museum was apparently significantly ahead of its time in the acceptance of photography as an art form. But other evidence suggests that Cameron’s photographs were collected not as works of art, but rather as source material for other makers. (And here it is interesting to note that Cameron herself instructed her gallery to charge artists half price for her prints.) In the original museum registers, the photographs were listed as ‘figure studies from nature’ and ‘portraits and studies from nature’ and similar classifications were written on the mounts, as on the example above. In an 1868 index to the photographs collection, ‘Mrs Cameron’ appears under the heading ‘Figure Studies’, along with photographs of drawings by Raphael, Mantegna, Millet and Dürer.

The South Kensington Museum thus equated photographs ‘from life’ by Julia Margaret Cameron with photographs of Old Master drawings, classifying both as two dimensional works that could be copied by artists and designers. Cole took this lack of differentiation among genres even further. In July 1860, when defending the work of the Photographic Department of the South Kensington Museum (which produced photographs of art and architecture, sometimes for sale to the public), he argued that an original drawing by Raphael was ‘not finer in quality’ than a photograph of a drawing by the artist. So by extension he seemed to place equal value on a drawing by Raphael, a photograph of a drawing by Raphael and a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron.

Today it has become commonplace for photographs made for one purpose, whether as scientific documents or family snapshots, to be appreciated or appropriated as ‘art’. What is much less familiar is the possibility that a photograph created as a work of art and still considered a work of art – which seemingly has always been a work of art – might have been regarded as a record photograph in its own time. At the V&A, over past 150 years, Cameron’s photographs have been transformed from the works of art Cameron intended them to be into the useful source material Cole considered them to be, and back again.

Marta Weiss is Curator of Photographs at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Her recent projects include the V&A exhibition Julia Margaret Cameron (28 November 2015 – 21 February 2016), to mark the bicentenary of the artist’s birth and the accompanying book, Julia Margaret Cameron: Photographs to electrify you with delight and startle the world, co-published by MACK and the V&A.

[1] Quoted in John Physick, Photography and the South Kensington Museum, London, 1975, p. 5.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Circe, 1865, albumen print from wet collodion glass negative. Museum no. 45140, courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Julia Margaret Cameron, Circe, 1865, albumen print from wet collodion glass negative. Museum no. 45140, courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London