Regine Petersen: On Devastation & Other Stories, by Natasha Christia

9 Nov 2015

How are we to deal with the collision of images and text in the work of Regine Petersen? For it is a collision, a deliberate one. When compiling data for the essay accompanying ‘Find a Fallen Star’, I found myself exploring the interweaving of pictures and the written word. A double equation at work emerged before my eyes: texts therein operated like visual unities as much as images were equivalent to language blocks. Petersen instigates this sort of dialectic coupling. The visual material she employs (be it archival resources or her own photographs) is not meant as a plain illustration of the texts she cites, neither the other way round. There is no intention of doing so whatsoever. It rather serves as a disquieting counterpoint that renders meaning milky and sub-aqueous. In its semantic richness, meaning expands amidst an automatic writing on random occurrences and their unpredictable outcomes to human fate.

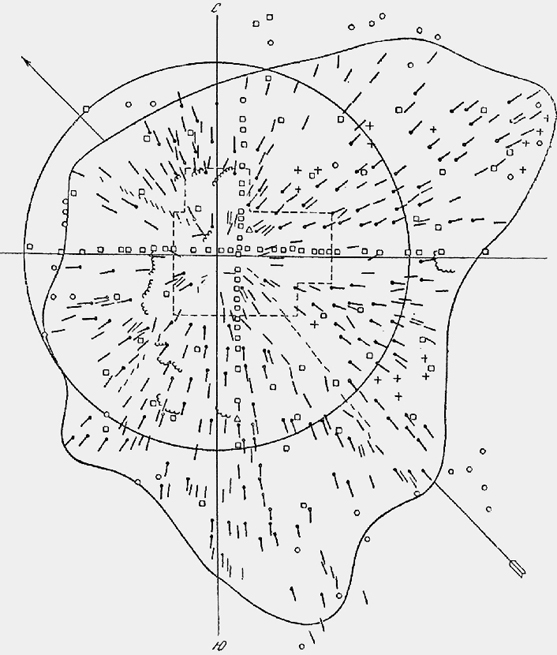

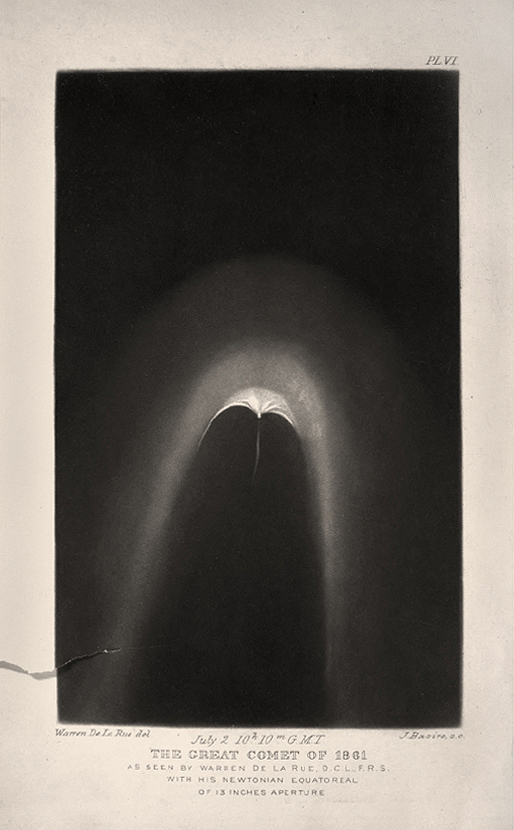

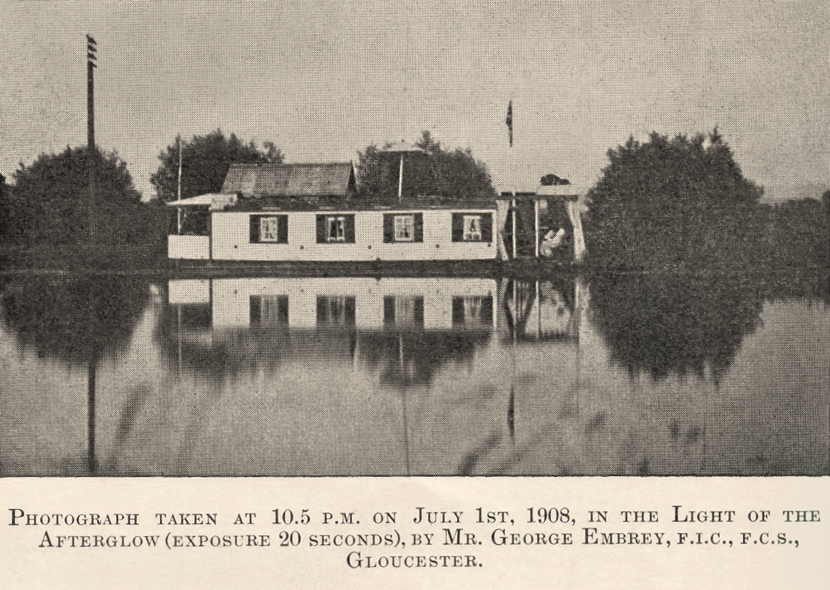

The Tunguska incident showcased in this feature conforms an imaginary blank chapter of ‘Find a Fallen Star’. It is a variant albeit not a less significant case in Petersen’s relentlessly expanding archive on meteorites. On June 30 1908, just after seven in the morning, an explosion took place over the Siberian Taiga. It is believed to have originated from an incoming comet or asteroid that produced an airburst of five to ten kilometres above the earth’s surface without actually hitting it. Despite the fact that the blast centre was remote and uninhabited, people felt the shockwave within forty miles from ground zero. The explosion reverberated in illuminated skies visible to distant areas of the world. It knocked down about eighty million Taiga trees over an area of 2,000 square kilometres and killed hundreds of reindeer. Its energy was estimated about 1,000 times greater than that of the Hiroshima bomb. No impact crater was found.

Contrarily to the three chapters of Find a Fallen Star (‘Stars fell on Alabama’, ‘Fragments’ and ‘The Indian Iron’), wherein the irruption of meteorites to earth gives rise to a chain of relatively un-dramatic, non-sensational events, the Tunguska case is a hazardous tale of destruction. And yet, here, the piece of cosmic stone that once struck through the atmosphere provoking environmental disaster on an unforeseen scale is up to this day evinced as a non-witnessed and non-tangible forensic record, relegated to the realm of speculation. What remains is the blast that Petersen literally enacts in the semantic clash of images and texts. In their openness, images and texts turn into indexical containers of concocted suppositions and ghostly stories in need of decoding. They wind and connect from one pairing to the other, exercising a quasi-physical impact on us. The rest is History and Myth.

While conducting research on the origins of the Tunguska explosion, I stumbled upon a handful of scientific and other fabulous conspiracy theories, ranging from Nikola Tesla’s experiments with wireless transmission to UFOs or mosquito explosions. Petersen’s approach performs how this information noise collides with the object that remains miraculously absent. Incomprehensible, ungraspable, the object is replaced and transformed into something else. A sort of visual pastiche conjectures a disparate global whole that paradoxically mends up to the Tunguska reality: Tree rings, illuminated skies, a little graphic of the blast with a ” bird’s view of flattened trees as well as different told and re-told perspectives of its destructive power (by foreigners or the local Evenki people). All these visual and textual testimonies move along a line of long vs. short exposures and cosmic vs. mundane temporalities, conforming an enthralling narrative sequence on minorities, lost words and eclipsed cultures.

Weaving in and out of facts, photography has this inexplicable side effect of absurd meaninglessness. Rather than filling the holes, it opens new ones. While its natural inclination is to provide a perspective of the past, it exposes the anomalies of interpretation and what is simply out of reach as if offering redemption to the phantoms generated in our times from time immemorial. It seems to me that beyond all beauty and catastrophe, ultimately there is nothing but the physical exhaustion of images. And devastation, mute devastation in the spirit that W.G. Sebald once described it in The Rings of Saturn:

“Where a short while ago the dawn chorus had at times reached such a pitch that we had to close the bedroom windows, where larks had risen on the morning air above the fields and where, in the evenings, we occasionally even heard a nightingale in the thicket, its pure and penetrating song punctuated by theatrical silences, there was now not a living sound”.

Regine Petersen is an artist based in Hamburg, Germany whose work explores the relationship between history, memory and myth. She recently published two books, Find a Fallen Star (Kehrer, 2015) and A Brief History of Meteorite Falls (Textem, 2014). She received her MA in Photography from the Royal College of Art, London in 2009.

Natasha Christia is an independent writer, curator and educator based in Barcelona. She has contributed the essay in Regine Petersen’s book Find a Fallen Star (Kehrer, 2015) and will be curating Docfield 2016 Barcelona Documentary Photography Festival.

Courtesy Regine Petersen

Courtesy Regine Petersen

Courtesy Regine Petersen

Courtesy Regine Petersen

Courtesy Regine Petersen

Courtesy Regine Petersen

Courtesy Regine Petersen

Courtesy Regine Petersen