SLANT: An interview with Aaron Schuman, by Federica Chiocchetti

21 Feb 2018

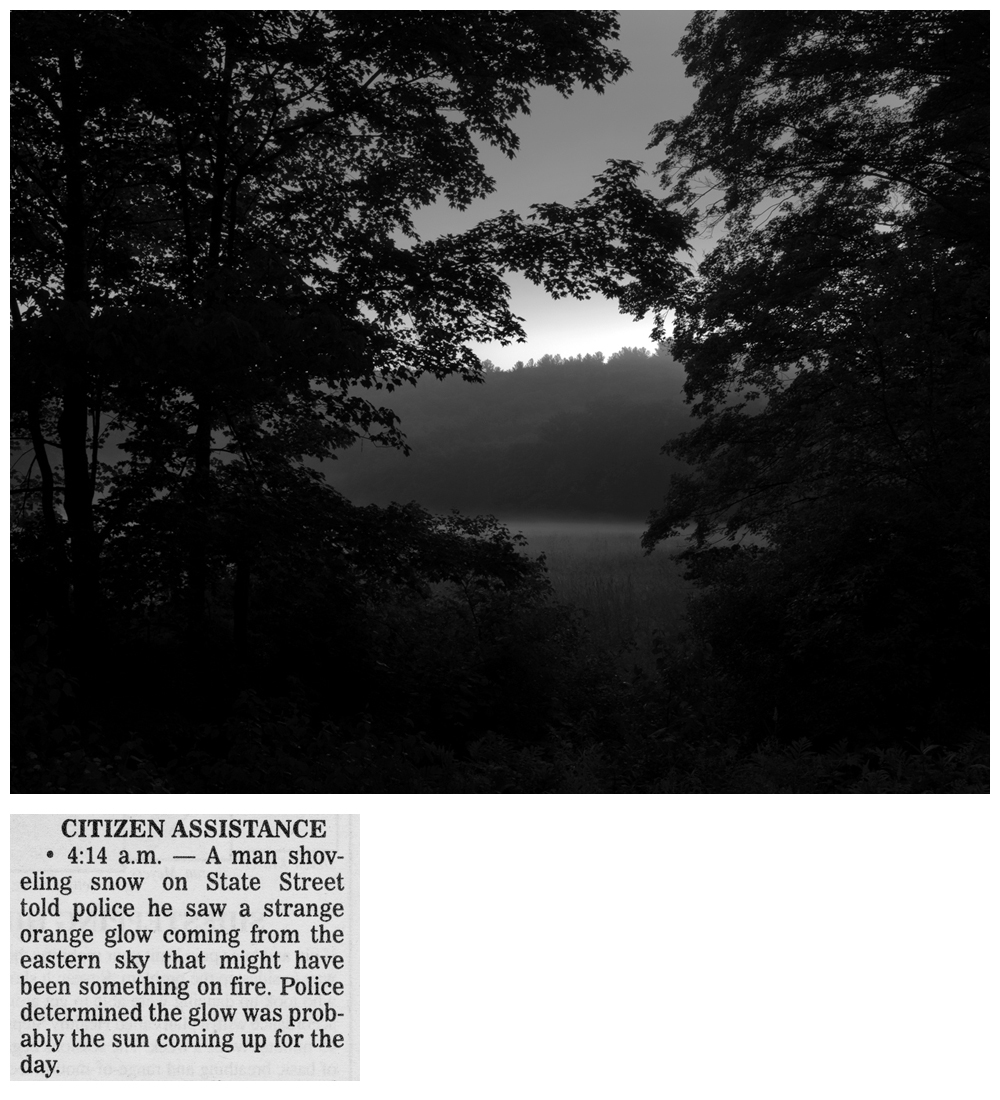

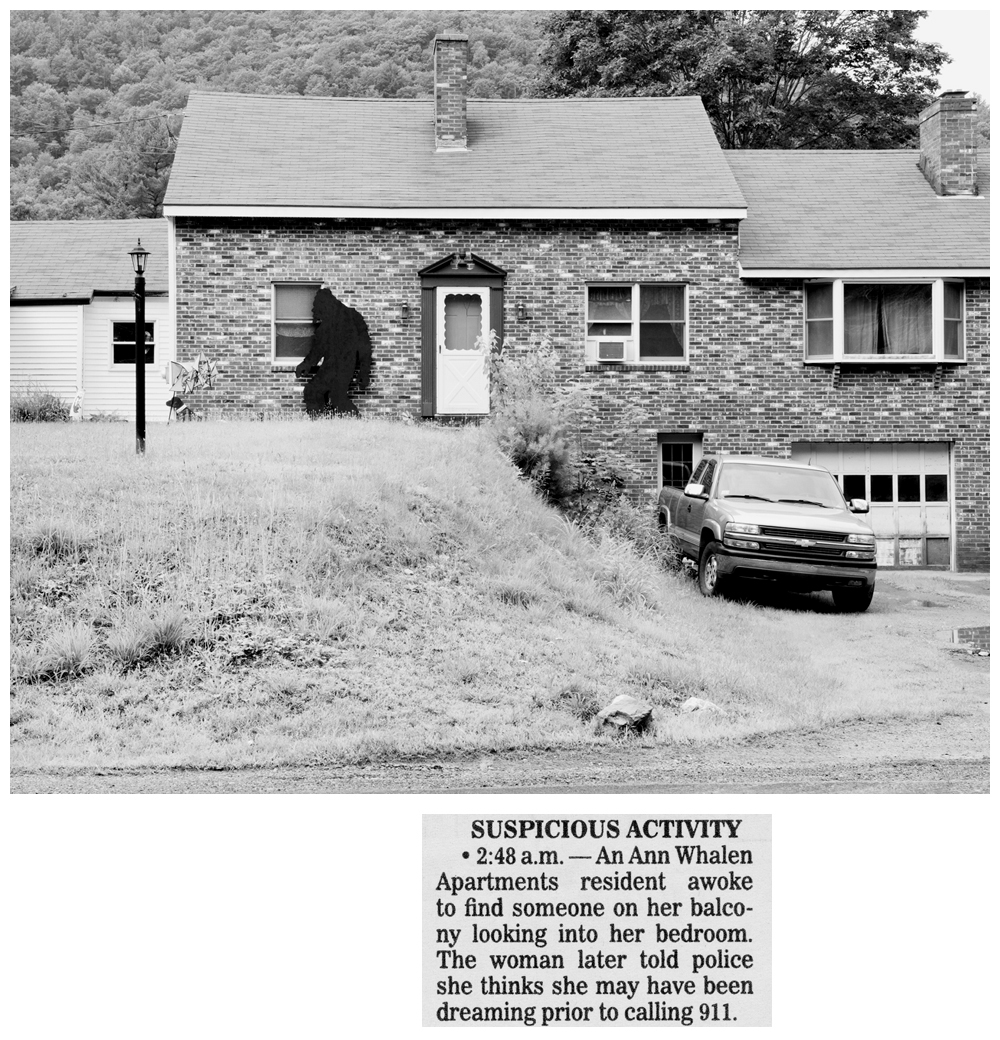

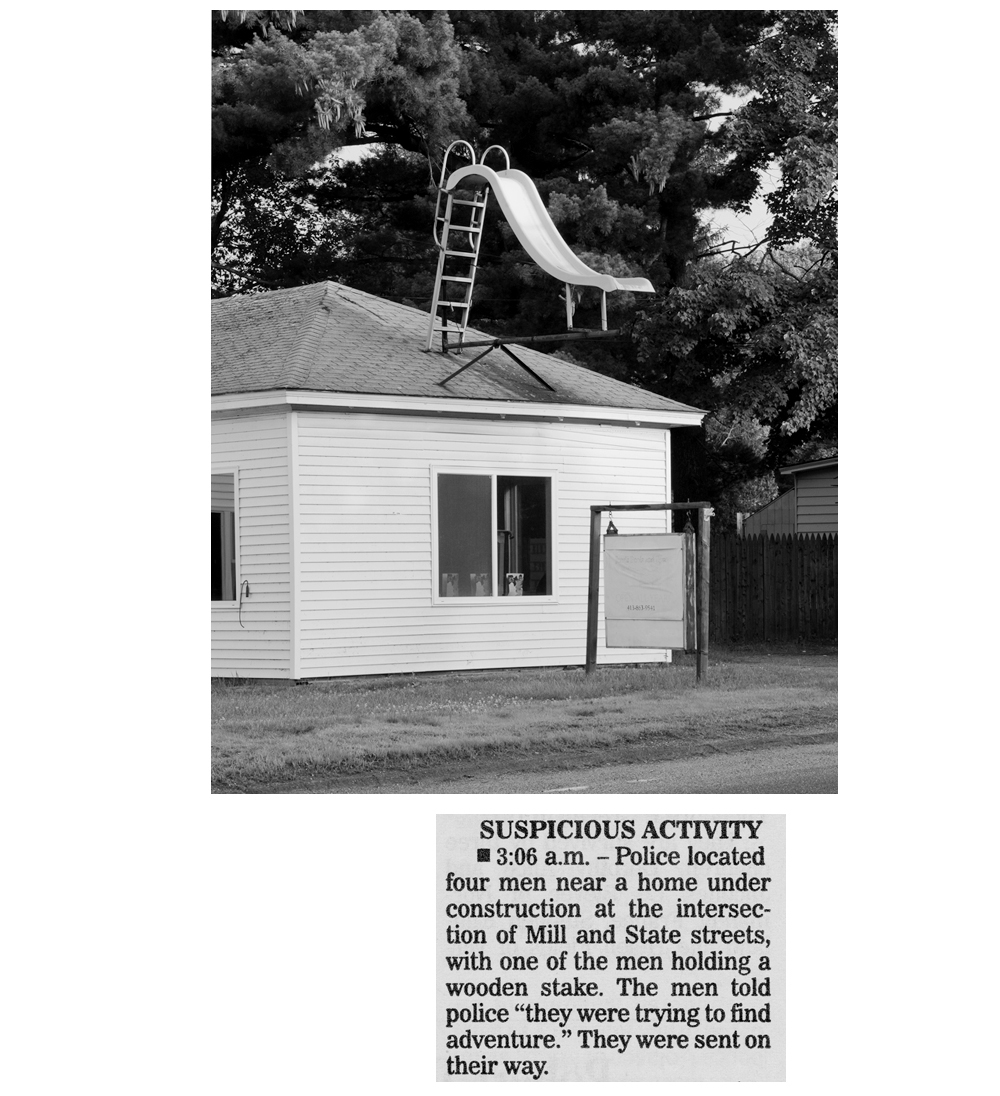

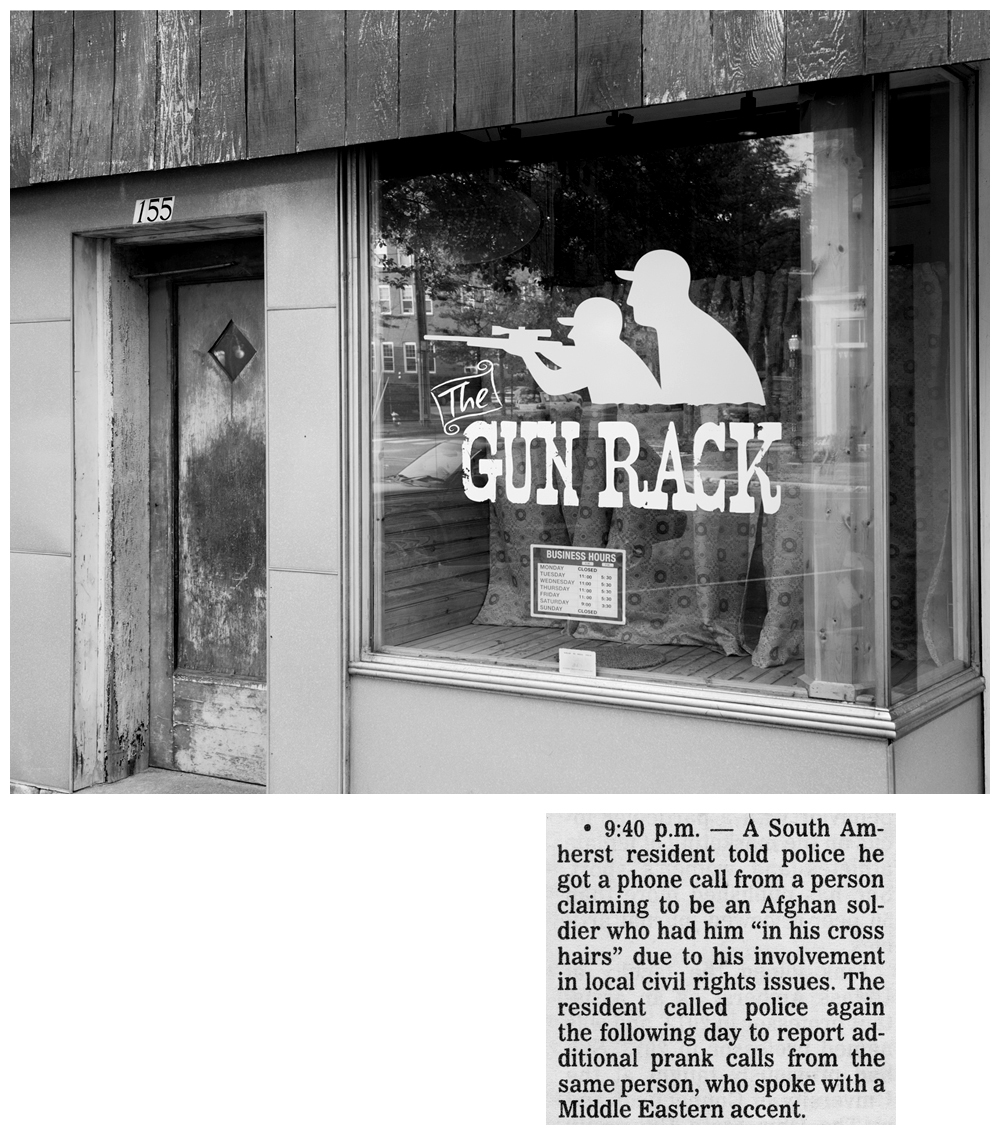

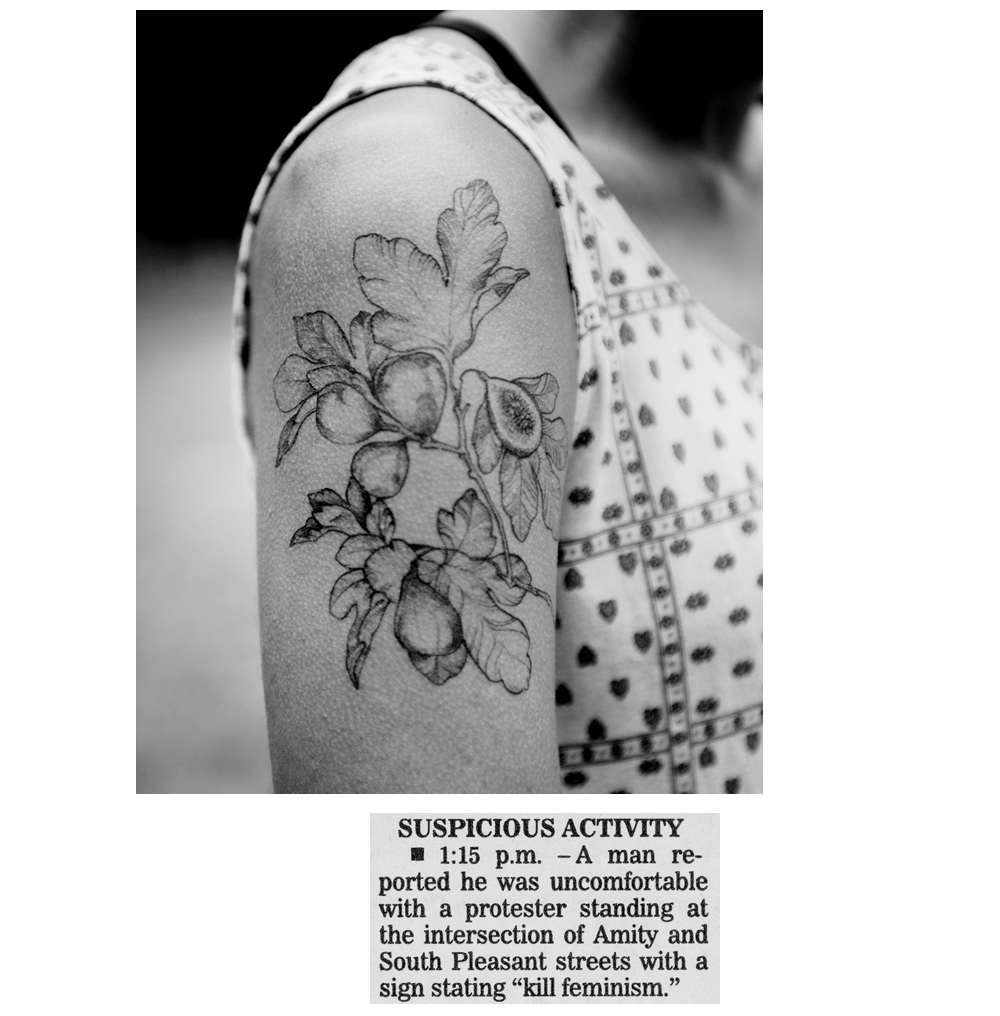

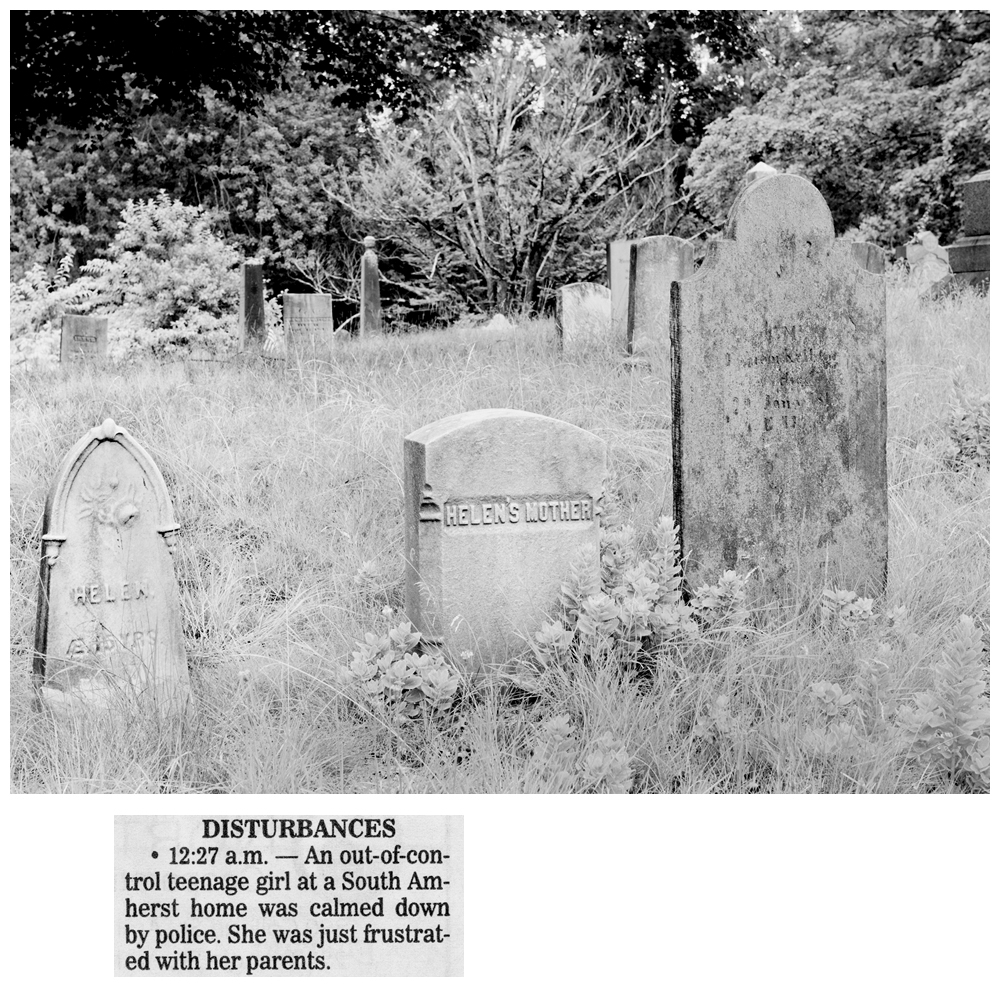

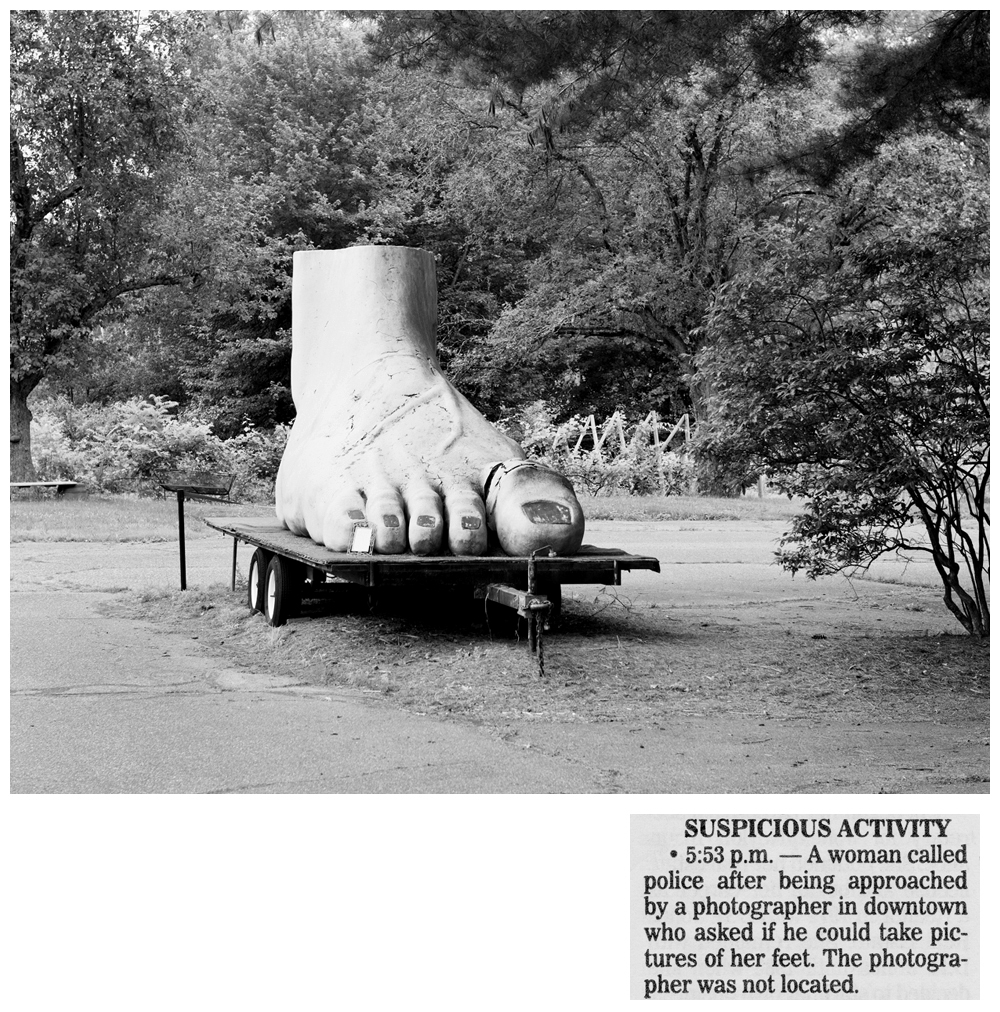

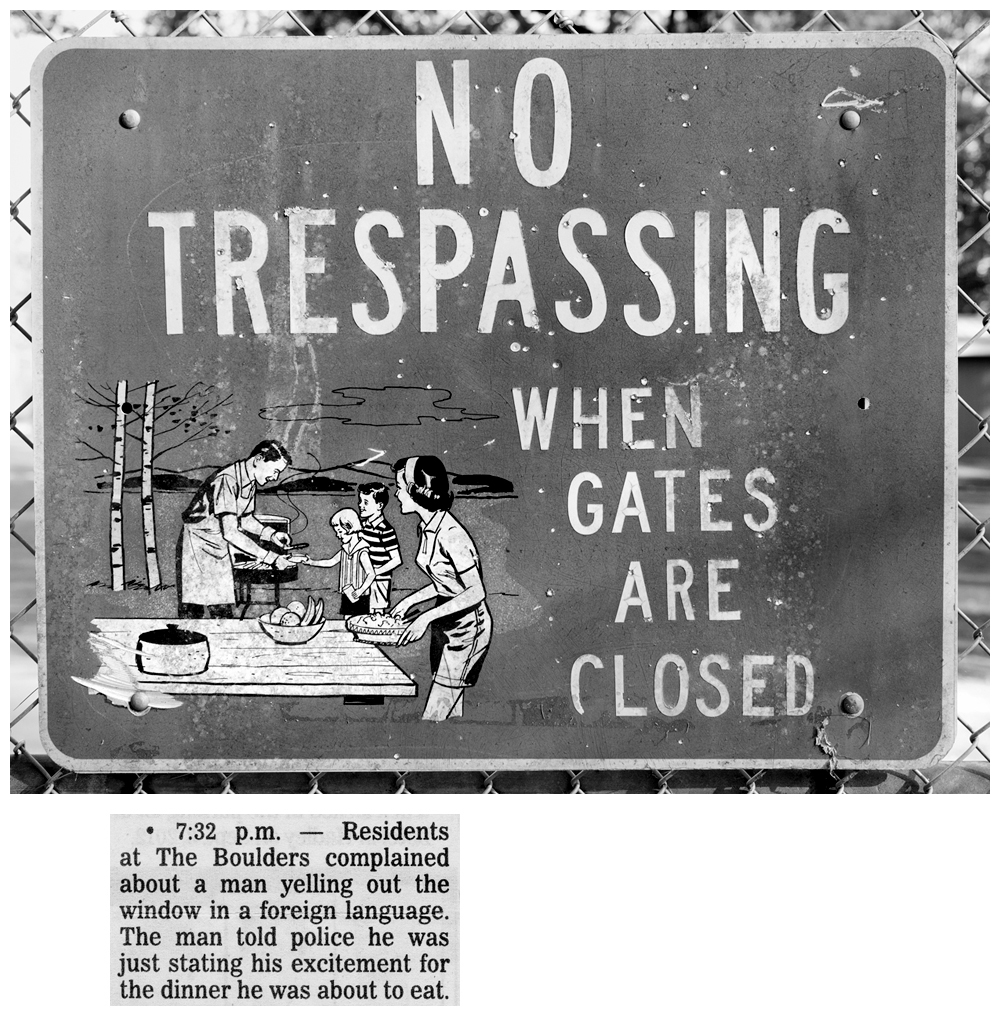

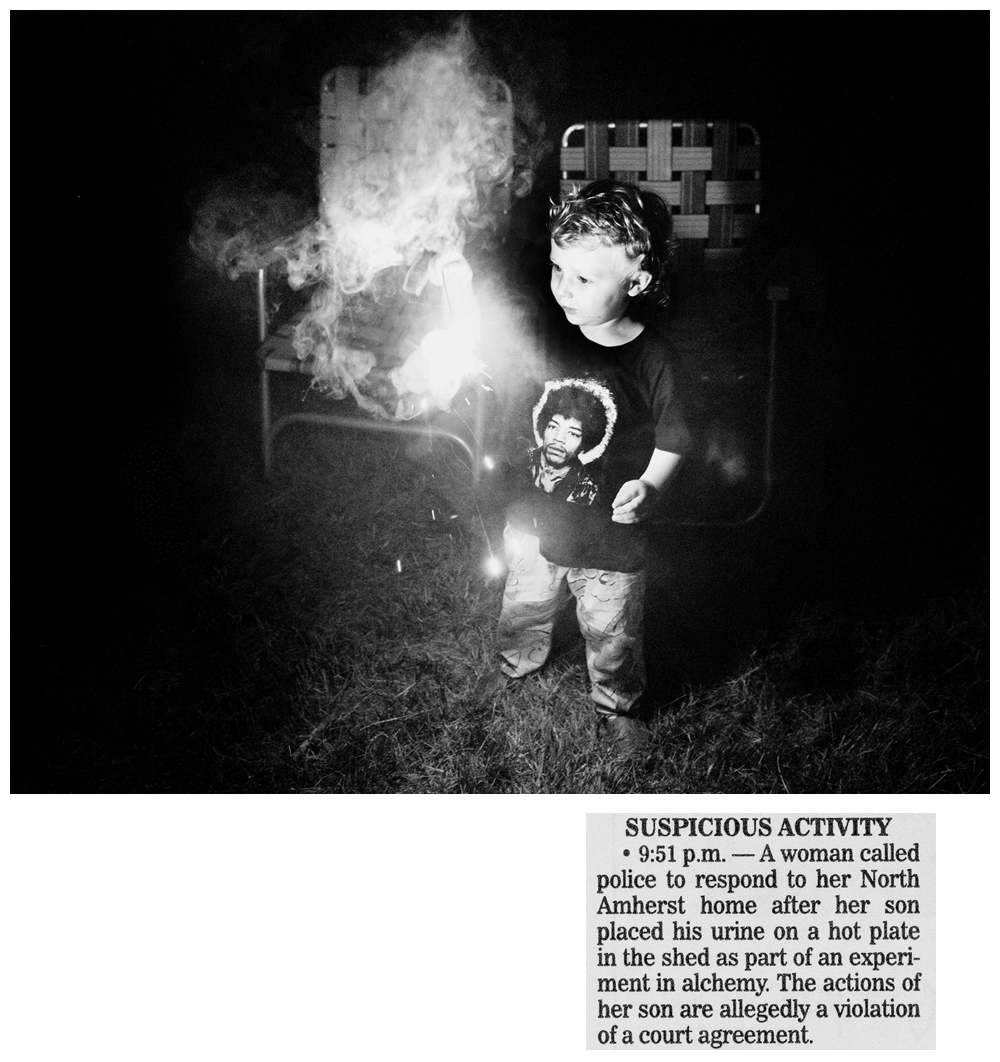

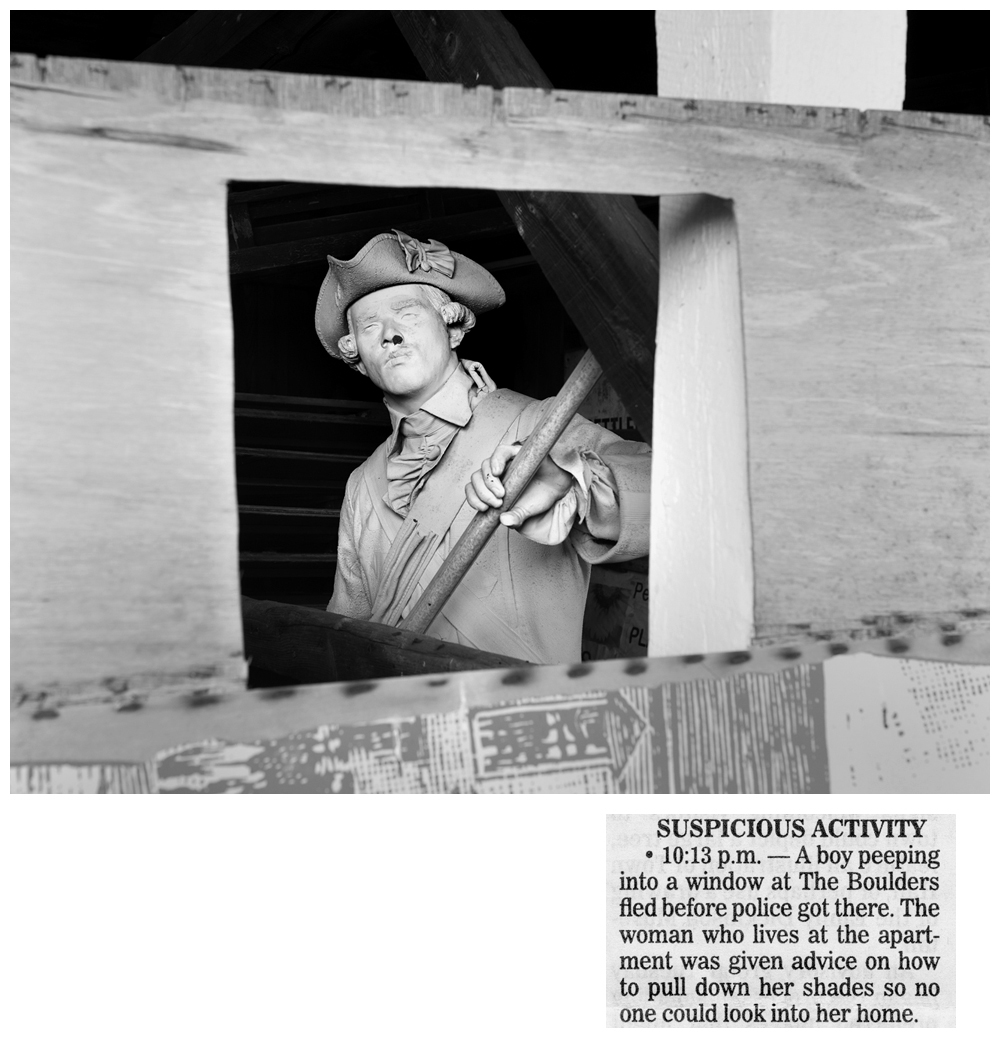

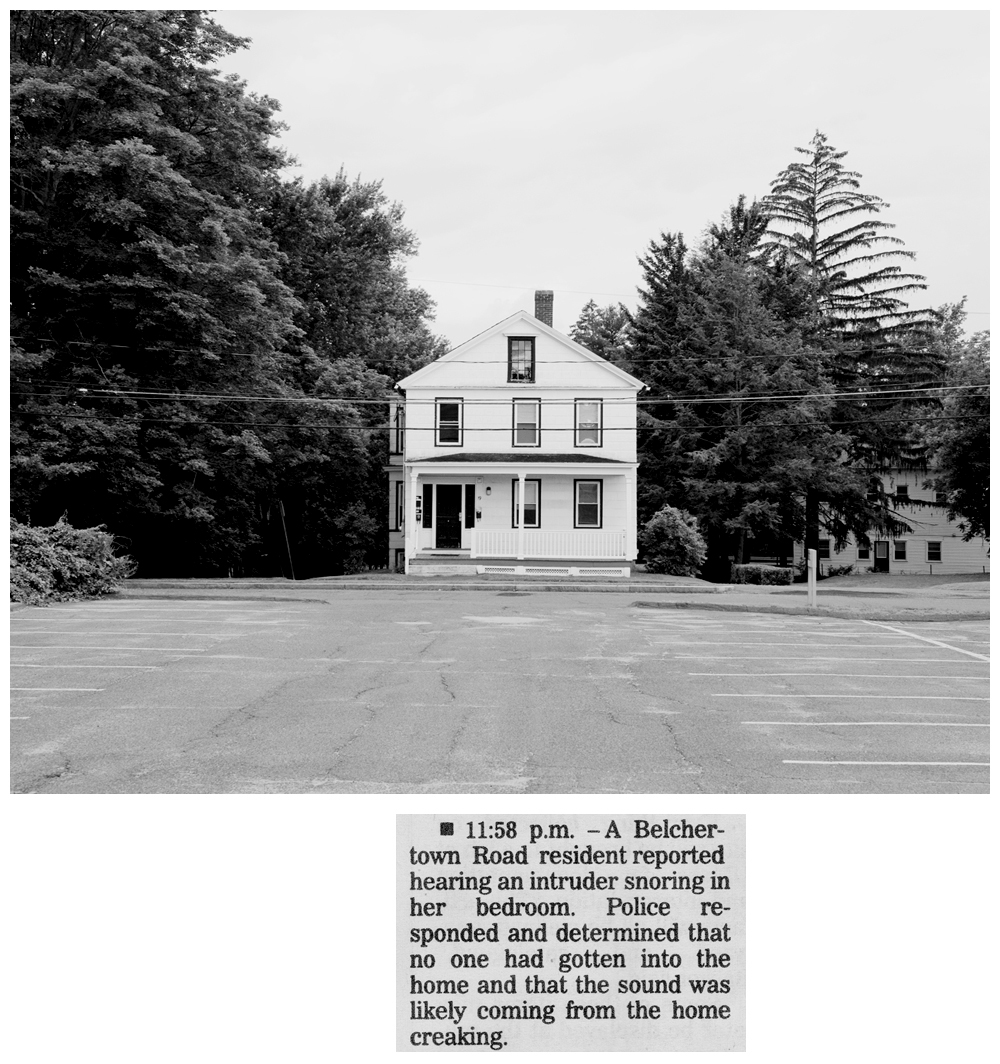

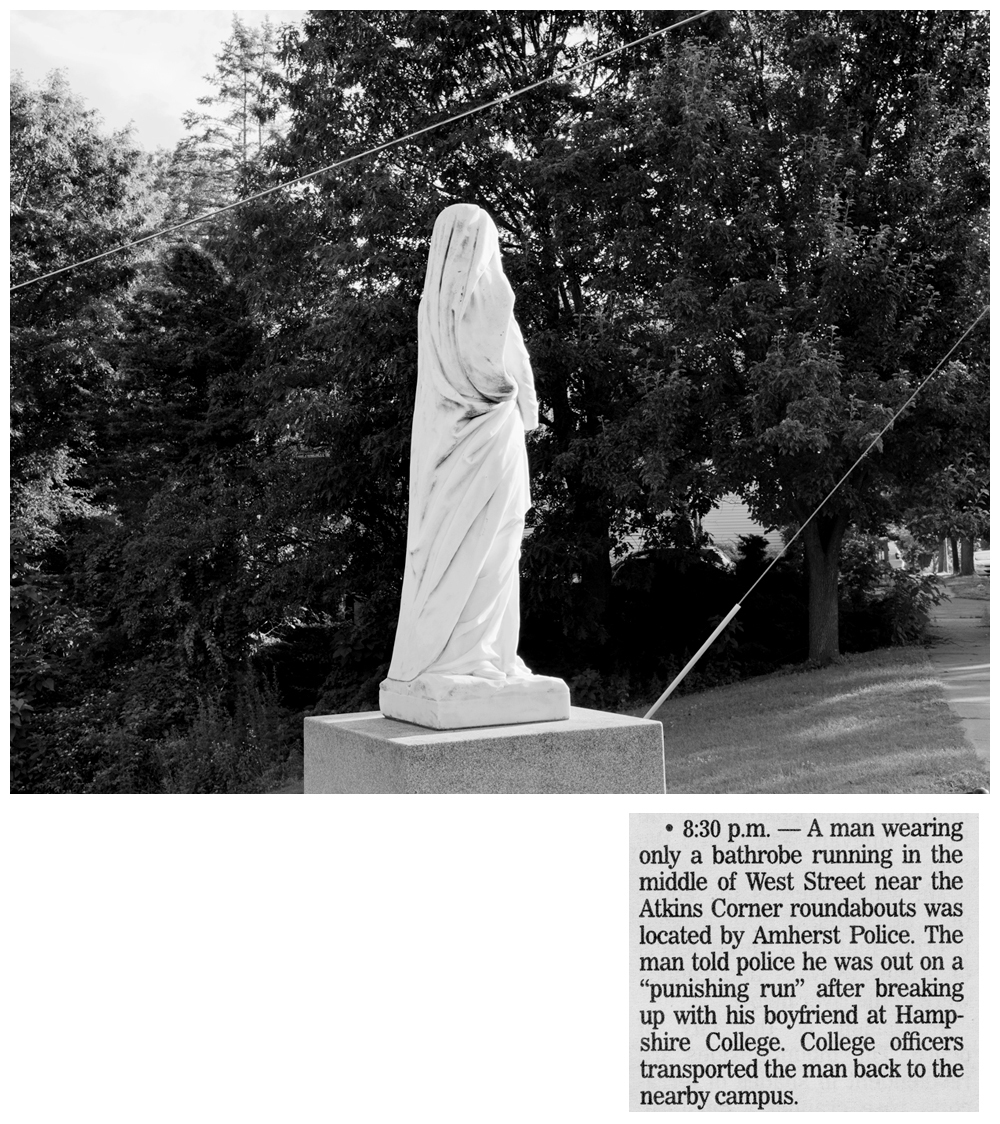

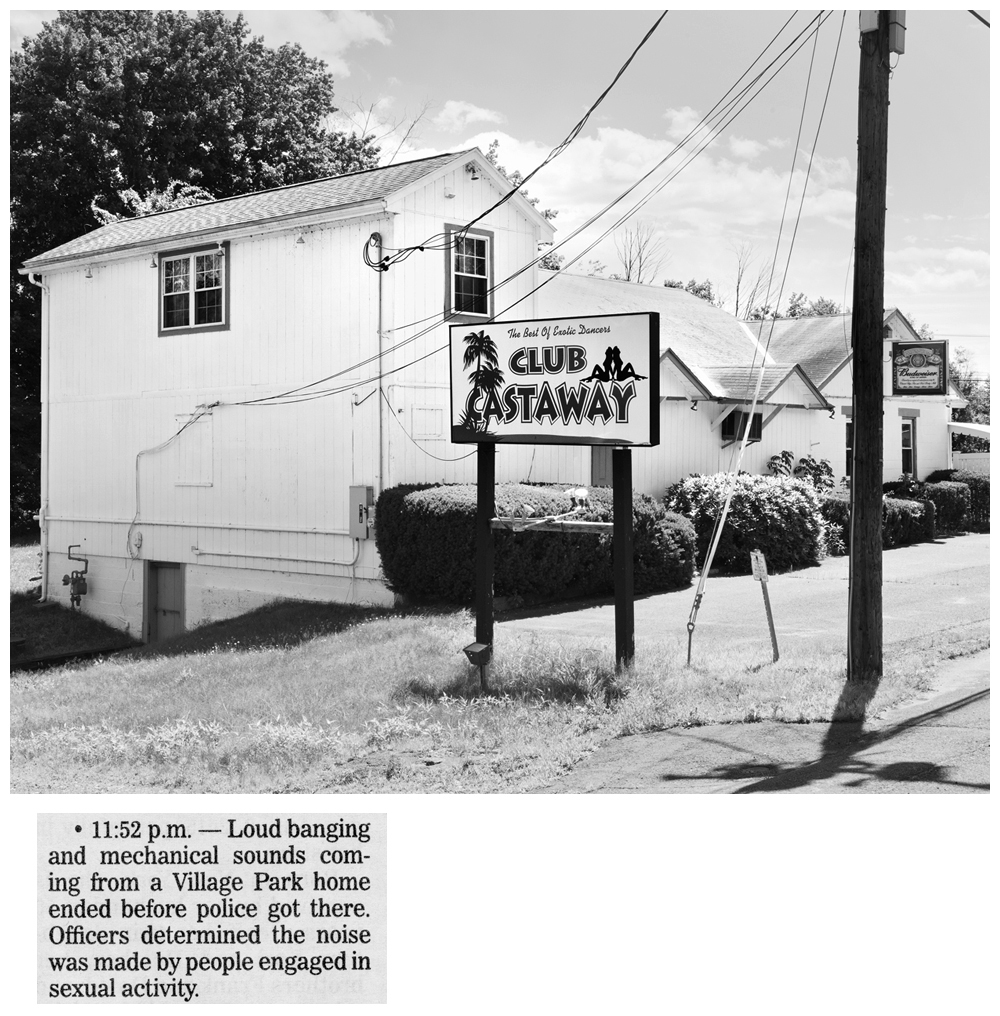

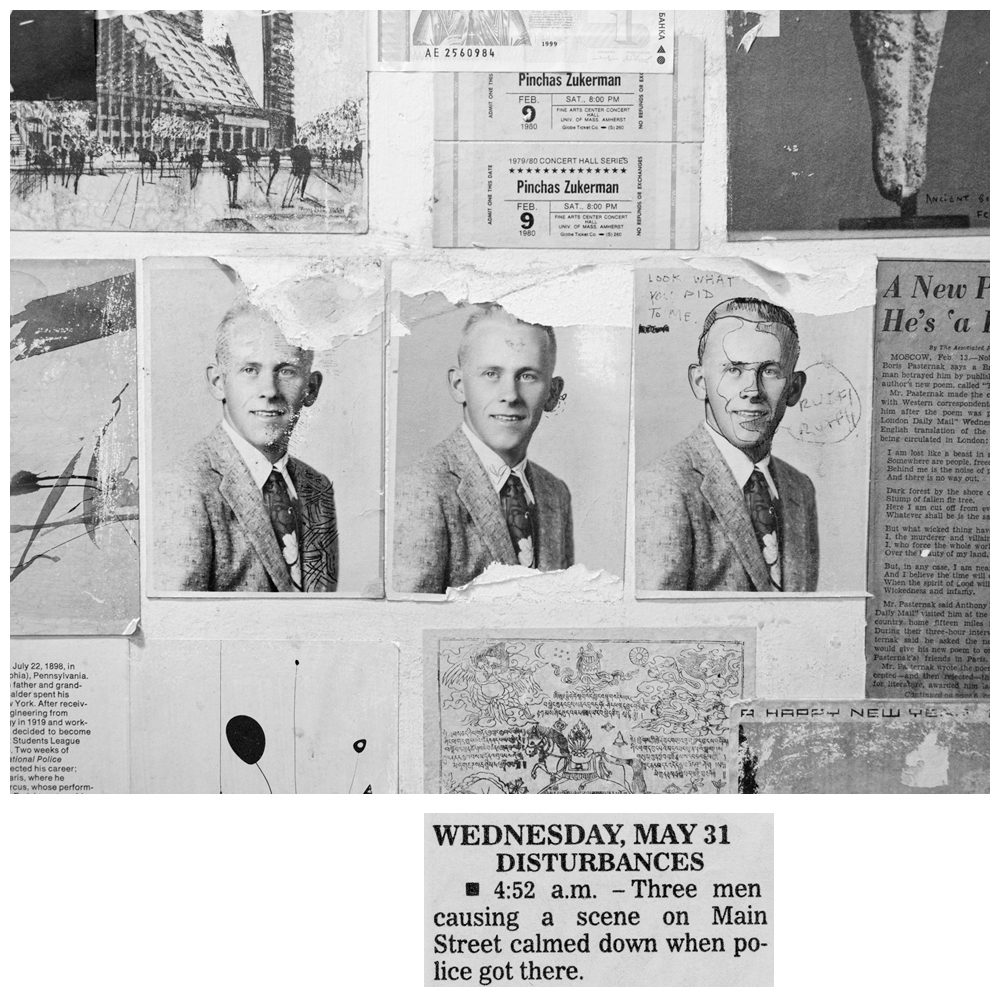

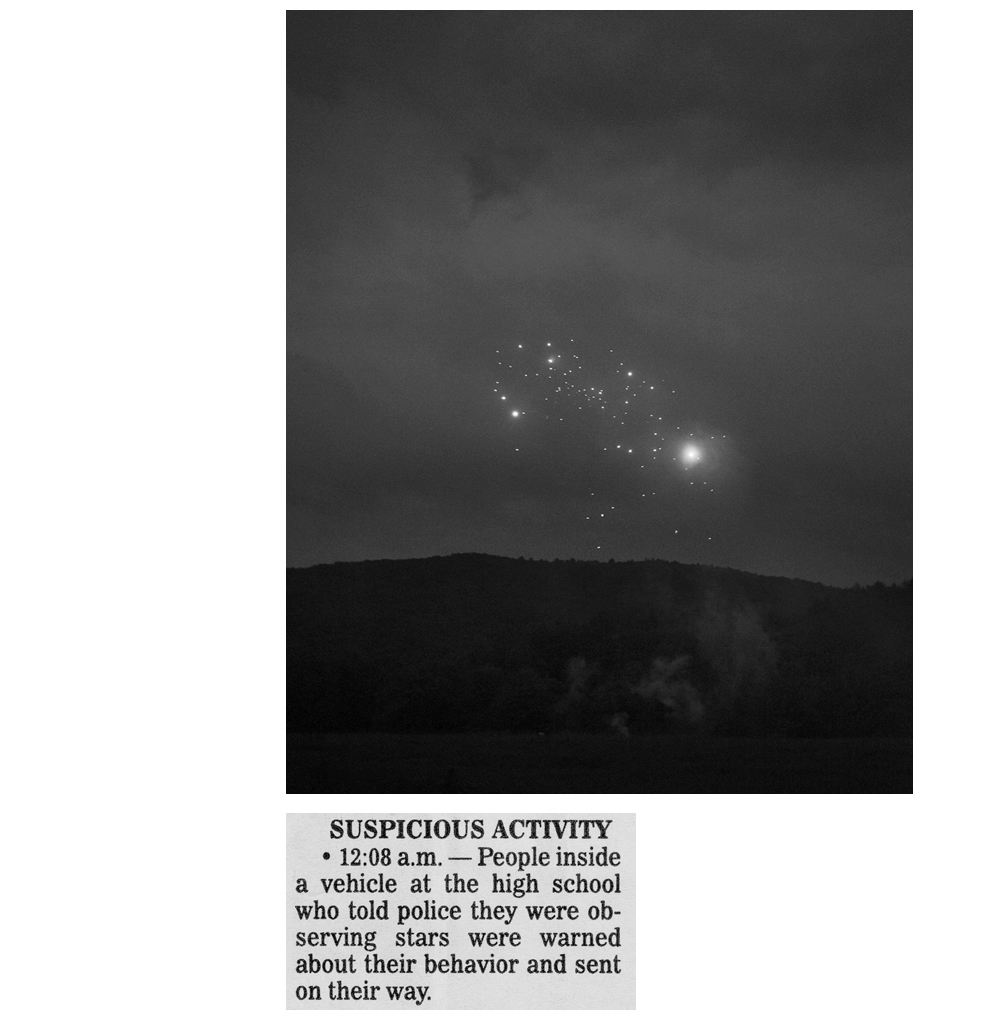

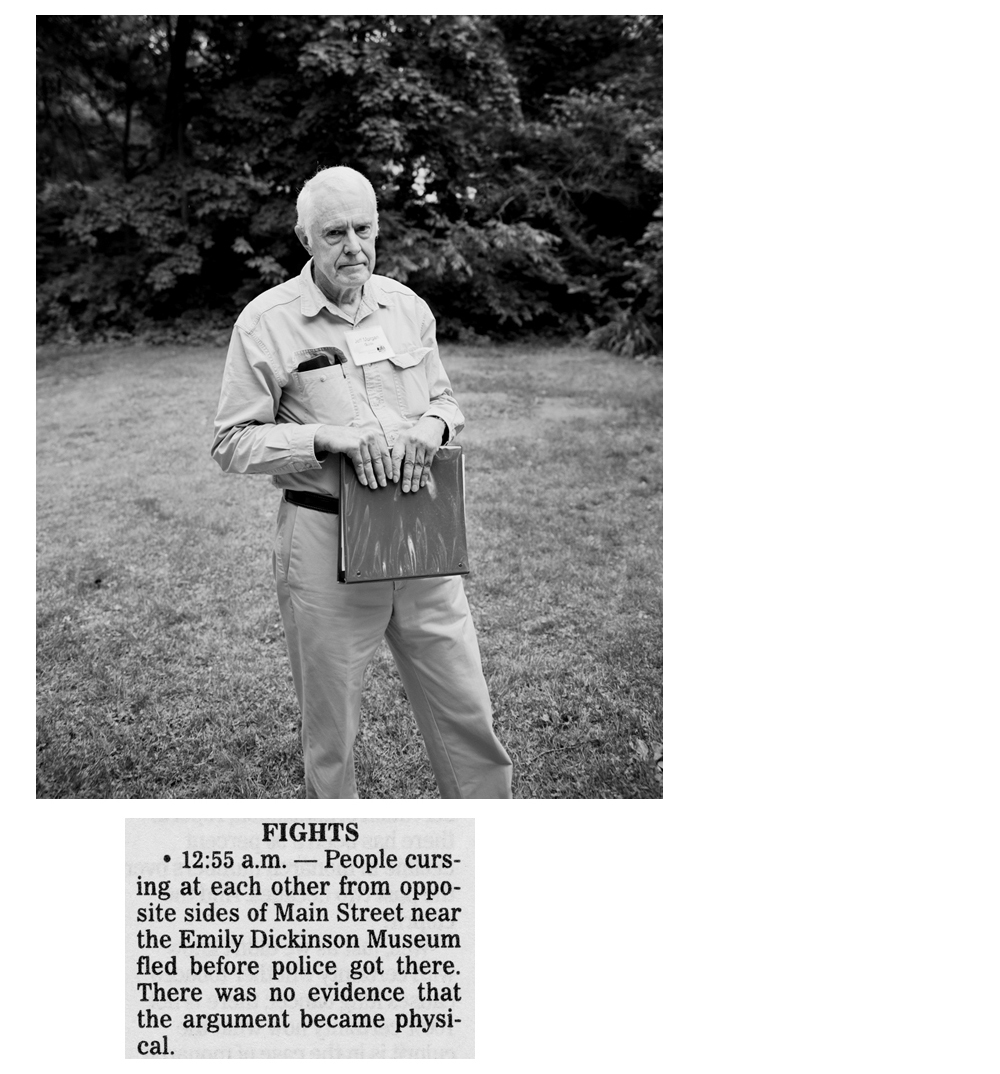

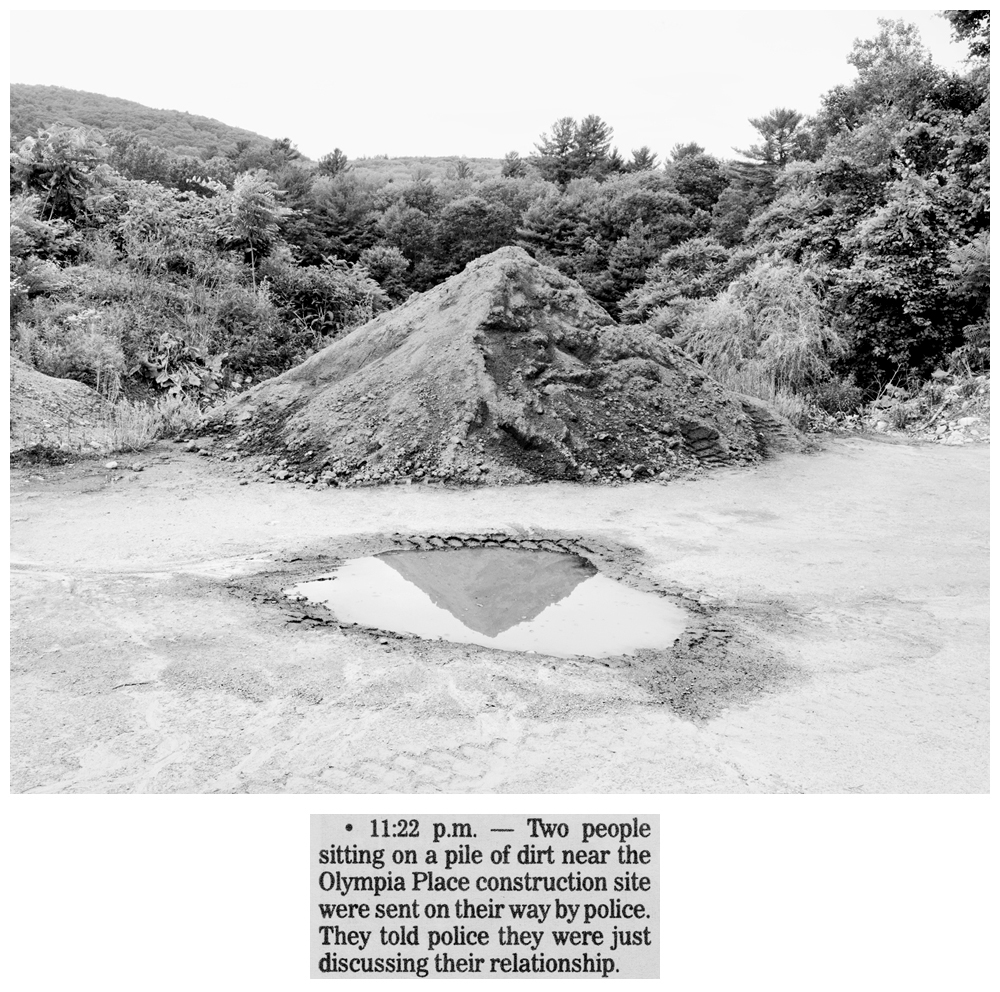

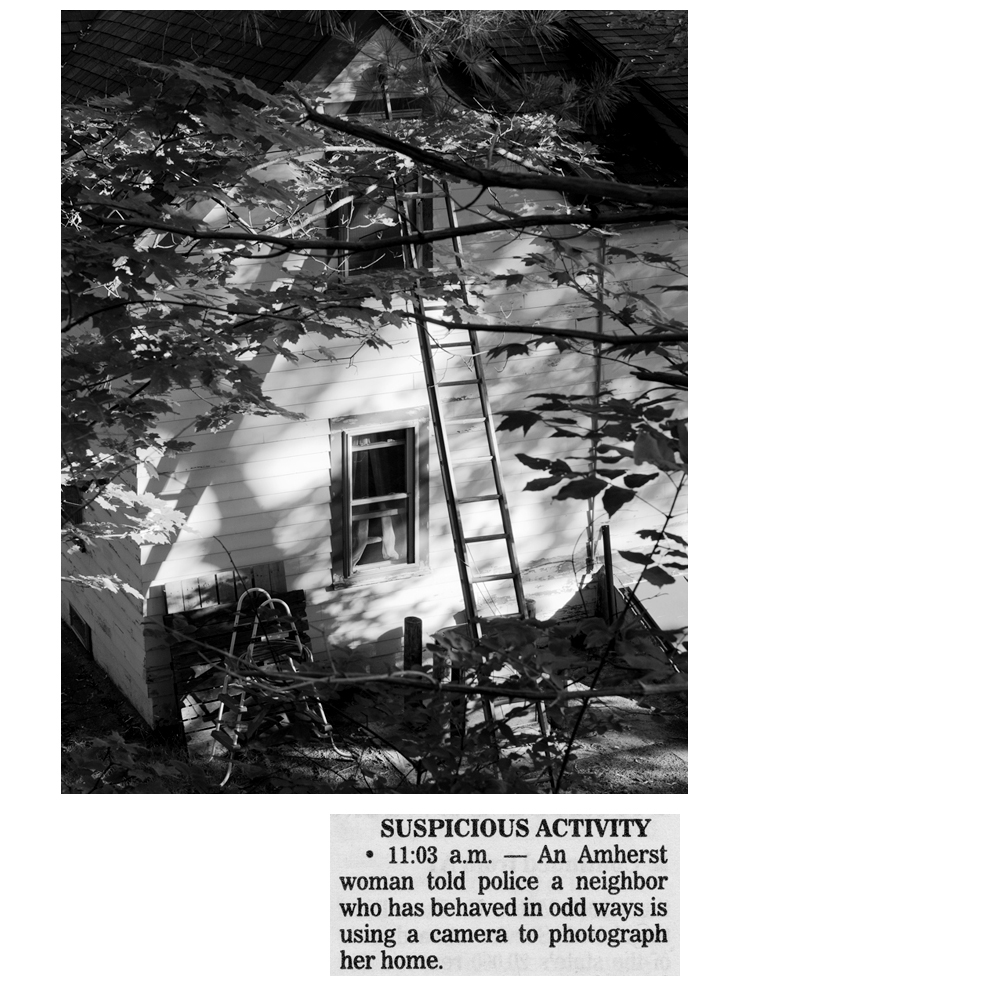

Federica Chiocchetti: First and foremost thank you so much Aaron for letting us premiere your new exciting body of work, SLANT, on the Photocaptionist, we are very honoured. Sometimes working under graphic design constraints of a website allows us to eviscerate the connection between different elements in a project. What we see here is a specific sequence of triptychs that you kindly crafted for the Photocaptionist. We first encounter, on the left-hand side, black and white photographs that you made within twenty miles of Amherst, Massachusetts, the summer 2017, in subtle response to a number of wonderfully bizarre ‘Police Reports’, which you collected – with the help of a special assistant – from the weekly local newspaper, the Amherst Bulletin between 2014 and 2017. These photo-text diptychs are in turn associated, also very subtly, with Emily Dickinson’s poem, Tell all the Truth but tell it slant. Could you please reveal to our dear readers how these elements relate to each other, and in general tell us a bit more about the genesis of your project?

Aaron Schuman: Well, firstly, thank you so much for featuring the work on the Photocaptionist; I feel very honoured as well! This project really began during a short visit to my parent’s house – in Amherst, Massachusetts – in the summer of 2014. One morning, I saw a copy of the weekly newspaper, the Amherst Bulletin, on their coffee table, and picked it up just to see what was going on around town. As I went through the various articles, I discovered a section entitled ‘Police Reports’, where various arrests were listed, and where the weekly activities of the local police were reported.

Amherst is a small, leafy college town in the hills of New England, and certainly isn’t rampant with crime, so most of the reports were of minor car accidents, lost and found dogs, noisy house parties, drunken arguments outside the bars downtown, and the like. But sprinkled within these stories were several genuinely surreal incidents that unexpectedly made me laugh out loud. Partly it was the activities themselves and their ridiculousness that cracked me up; but also it was the fact that the police were even involved, and that it was deemed news-worthy by the paper: ‘6:32 p.m. – A man described as having a “wild hairdo” on a West Street porch was not located by police. The man was likely a solicitor going door-to-door in the neighbourhood’. Additionally, it was the way in which each report was written – a short, matter-of-fact sentence or two, without a hint of irony or subjectivity, which somehow managed to encapsulate both the mind-numbing ordinariness of the place whilst also conveying its extraordinariness in the most dead-pan of ways. I found them somewhat poetic in a very spare and interesting kind of way, like something by William Carlos Williams or a short story by Lydia Davis.

Anyway, my dad – who was sitting with me at the time – asked what was so funny, so I started reading them out loud to him, and going through the back issues from previous weeks that were lying around; we laughed hysterically together all morning. (When I was around twelve or thirteen, my father took me to the stand-up comedian, Steven Wright, who was performing down the street from my childhood home in Northampton, Massachusetts – only a few miles from Amherst. Wright is an absolute genius when it comes to one-liners, delivered in the flattest, most deadpan of ways; it was probably one of the funniest nights of my life, and laughing with my dad in the living room that day brought me right back to it). So when I returned to the UK, I asked my father to cut out the ‘Police Reports’ each week, and send them to me from time to time. Every few months over the last three years a large manila envelope has arrived in the post, filled with these newspaper clippings.

After a year or so, once this archive grew and I realised that nearly every week there were at least one or two gems in there, the reports started to grow in my imagination – I was posting the odd one occasionally on Facebook under the headline, ‘Notes from small-town America’, and people seemed to really love them. I started feeling like I could potentially make some interesting photographic work out of them. Initially, I struggled to think of how I could make photographs that would stand up to the texts, because the texts were just so strong, specific and strange: ‘11:15 a.m. – Police were notified about a man who threw a temper tantrum while at a downtown office. The man, who was wearing a jacket with photos of deceased people stapled inside, was not located’. I thought about trying to document each incident like a newspaper reporter (but in retrospect, realised that this would be impossible), potentially staging images (much of Gregory Crewdson’s work is also made in western Massachusetts), or using archival ‘found’ imagery (which I have mountains of, sitting in boxes, gathering dust), or doing some sort of studio-based constructions (which I quickly reminded myself is not really my thing), and then eventually decided that perhaps it was best to simply let the texts speak for themselves. So I scanned them at huge resolutions, thinking that I’d make large-scale prints – in the spirit of Christopher Wool, Jenny Holzer and so on; appropriated, text-based conceptual art – and that would be that. Then last year, I made a couple of test-prints in this manner. But as a ‘photographer’ rather than a ‘conceptual artist’, it somehow didn’t seem satisfying enough; it felt a bit too easy and one dimensional for me, and I felt like the work was missing an important visual element.

Unfortunately, this spring, my father’s health began to deteriorate quite rapidly, so I decided to go home to see him and my mother over the summer. I figured that, in order to keep my head in a good place, the trip might also serve as an excellent opportunity to rethink the ‘Police Reports’ and try to make some photographs whilst I was in Amherst. I started thinking seriously about the place itself, and reconsidered a poem by Emily Dickinson that I was assigned to read in high school. She was born and raised (and is buried) in Amherst. And she wrote all of her poetry in a house that’s less than a mile from where my parents now live.

Ever since I first became interested in photography, and particularly in documentary photography, Dickinson’s poem – Tell all the Truth but tell it slant – has always stuck with me in many meaningful ways. The idea of the ‘truth’ being something that is too ‘bright’ and ‘dazzling’ to be told straight fascinates me as a photographer. Also, stylistically, Dickinson’s famous use of ‘slant rhyme’ appealed to me, particularly for this project. I realized that I might not necessarily need a photograph of a solicitor with a wild hairdo, or a man wearing a jacket with photos of dead people inside it, in order to make the project work, and in fact, it might be better to approach the photographic aspect of this project from a ‘slant’ angle.

So, when I arrived in Amherst in the summer, I simply started taking photographs that at first appear rather straight, spare and ordinary – mimicking the tone of the ‘Police Reports’ themselves – but have within them some subtle element that’s slightly strange, surreal or off-kilter. And then, once I had ten or fifteen strong images, I began the process of trying to pair them with ‘Police Reports’ in my collection that resonated with them in a ‘slant rhyme’ kind of way, as they brought additional circuitous and gradually dazzling new meanings and possible interpretations to both the texts and the photographs.

FC: And I find particularly interesting the fact that the title of your project, SLANT, also partly reflects your photo-text modus operandi. Within the promiscuous and fascinating sub-genre of image-text intersections, photo-text, which gained awareness with conceptual art, requires a serious craft of equilibrium to be effective. Harmony, between subtlety, irony and the ability to create a cloud of third meanings that goes beyond what is portrayed in the photograph and found in the words, is quite crucial. From suspicious activities against feminism, to which you responded with a somewhat cryptic close-up of a fig plant tattooed on a female shoulder, to disturbances provoked by alleged feet fetishism that you associated with a more literal, yet fantastically exaggerated and effective image of a massive foot statue, could you tell us a bit more about your slant photo-text ‘method’?

AS: Yes, as I said, for this project I tried to negotiate the relationship between text and image via the notion of the ‘slant rhyme’, where two words almost but don’t quite rhyme – a tool that poets, and Dickinson in particular, often use to create dissonance within a rhyme scheme so that the reader is thrown off-balance, but only slightly, and has to pause, reread, refocus and reassess the words and their meanings. For example:

“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all –

In this stanza by Dickinson, ‘soul’ and ‘all’ almost feel right, but not quite; the stanza seems both straightforward on the surface but curiously inharmonious underneath, and makes what might otherwise seem like an easy and rather trite conceit much more complicated and complex.

So, for example, in the case of the fig tattoo photograph that you mention, there are many layers. Firstly, I should explain that I grew up in Northampton, Massachusetts – eight miles from Amherst – which is the home of Smith College, a long-established all-women’s liberal arts college where notable feminist icons such as Betty Friedan, Sylvia Plath, Gloria Steinem, and many more studied; it’s Program for the Study of Women and Gender continues to be one of the most important and prominent within academia, and attracts feminist scholars from around the world. Furthermore, Northampton is often referred to as ‘the lesbian capital of America’, as its population includes the most lesbian couples per capita of any city in the United States. Along with the surrounding area (Amherst included), it is considered one of the most liberal, left-leaning, ‘open-minded’, ‘alternative’ or ‘countercultural’ communities in America.

What I find fascinating about that particular ‘Police Report’ – ‘A man reported that he was uncomfortable with a protester standing at the intersection of Amity and South Pleasant streets with a sign stating “kill feminism”.’ – is the protest itself, and the fact that today, within Trump’s America, such an ultra-conservative sentiment has become a part of public landscape, even within the most progressive of places. But I’m also interested in the fact that the police were contacted because the protest was deemed threatening; that within this extremely liberal environment, someone’s public expression and protest via ‘free speech’, albeit of their very conservative beliefs, was deemed aggressive and provocative to warrant police attention, and met with such a conservative response. Also, the fact that it was a man who reported that he was ‘uncomfortable’ with this particular act of ‘protest’ is rather intriguing. And furthermore, there’s the irony of the street names – ‘Amity’ and ‘Pleasant’ – which imply certain, very American aspirations on the part of the original town planners, but which are somewhat undercut by the activities described as occurring on those streets today. So the text is already incredibly loaded in so many ways.

Then, there’s the story behind the photograph. One afternoon whilst visiting my parents, I decided to go on a tour of the Emily Dickinson Museum (down the street, in her former home), and while I was waiting around for the tour-guide to show up, a young woman arrived and joined the group. She had the most striking tattoo, a botanical drawing of a fig branch – it was genuinely one of the most beautiful tattoos I’ve ever seen, and I kept staring at it throughout the hour-long tour, which in hindsight I imagine made her pretty uncomfortable. Anyway, through research that I’d done for another project, I knew that the fig had all kinds of symbolic meanings, Biblical and otherwise – the Tree of Life, the Tree of Knowledge, Adam and Eve sewing fig leaves together to cover themselves during The Fall, the fruits own sensual and sexual suggestiveness, and so on – so after the tour was over, I went over and asked her if I could photograph her arm. She guardedly said yes, and afterwards I asked her, “Why a fig?” – “Its kind of embarrassing”, she said, “It a reference to The Bell Jar. You know, Sylvia Plath?”[1]

By putting these two elements together – at a ‘slant’ – rather than simply photographing what is presumably an angry, white man standing on a street corner with an annoyingly confrontational sign (something I actually never saw during my visit), all of these different layers and meanings clash, coalesce and converge, creating what you’ve described as an additional ‘cloud of third meanings’ and new possibilities for interpretation, which neither the text nor the photograph could possibly contain independently of one another.

When it comes to the photograph of the giant foot you mention, that was one of those brilliant accidents; pure photographer’s luck. In the collection, I actually have multiple Reports from over the last three years in which the police were contacted because someone asked to photograph the ‘victim’s’ feet (as you say, it could be a prolific local foot-fetishist, or more likely several undergraduate art students trying to fulfil some brief given to them by one of the surrounding colleges), so photographing a foot was definitely in the back of my mind when I decided to make the trip. But as I was driving from the airport to my parents’ house on the first day, I passed this bizarre foot sculpture on the outskirts of Amherst – it was in the parking lot of a local ‘winery’ (something to do with squashing grapes with bare feet, I guess, as the area is certainly not known for its wine production) – and it was just too good to be true. It was just so weird, with its knobbly knuckles and stunted toenails; I couldn’t have asked for, or imagined, anything better.

FC: I would like to share a passage that I found in Hilde Van Gelder and Helen Westgeest’s seminal book Photography Theory In Historical Perspective, on Sekula’s photo-text position: ‘To [Alan Sekula], a picture should not be too dependent on its caption only. Any further text that relates to the picture should not operate “Oz-like, from behind the curtain”. When this is the case, Sekula argues, the picture only allows for a textual discourse in a strictly separated, art-critical realm’[2]. What do you think about it?

AS: This quote is interesting, because it kind of aligns with two aspects of my decision-making process when it comes to SLANT. Firstly, it helps me understand why I instinctively felt that making photographs in which the content very directly connected (or ‘rhymed’) with the individual ‘Police Reports’ wasn’t going to work – why a photograph of a solicitor with a wild hairdo or an angry man protesting feminism on a street corner would undermine both the text and the image within this work, and why a photograph of a giant homemade foot sculpture works so much better than simply a picture of a foot alongside that particular text. The more literal photographs would have been entirely dependent on the textual element, they wouldn’t have made any sense otherwise, and the text would have been put into this primary position of authority whereby it not only controls but also overpowers the images. So much so that the pictures would seem both supplemental and expendable. Honestly I found that the ‘Police Reports’ were so strong that I really struggled to work up the courage to try and match them photographically, and the ‘slant’ approach seemed like the only way forward, so that there was an equally-weighted rather than ‘Oz-like’ relationship between text and image.

Secondly, this quote also helps me understand why my initial attempts at simply producing large scale, appropriated images of the ‘Police Reports’ – where text and image were, in a sense, merged into one – didn’t seem to work either. As Sekula suggests, this meant the works could only be considered and taken seriously with an art-critical discourse and a gallery context (and really, it was only the scale and production value that would have allowed this to even happen); otherwise they were simply a quirky collection of news stories that might be gathered together in a little novelty book to be sold in the humour section of a mainstream bookshop at Father’s Day or Christmas. Like the Facebook posts, they were fun, but just a bit too easy.

FC: And image-text wise, if you were to mention an inspiring figure, who would that be?

AS: Two of my favourite works of art come from John Baldessari’s Goya Series (1997) – one is a plain photograph of a paperclip on a light-grey background with the word ‘AND’ painted beneath it; the other is a plain photograph of a freshly-sharpened pencil on a light-grey background with the words ‘SO MUCH AND MORE’ painted beneath it. I should also say that my favourite poem of all time is William Carlos William’s The Red Wheelbarrow, which in turn was inspired by the photographs of Alfred Stieglitz:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

Several years ago, I had the opportunity to interview Baldessari, and asked him directly about the relationship between text and image within his work. He stated:

“…I’m very interested in both language and imagery; I don’t really know why, but I find word and image equally important…I tend to use imagery kind of like a writer. Of course, even though English is now fairly universal, in a lot of countries somebody might still see the word “house” and not know what it means, because it wouldn’t be their word for a house. But if they saw an image of a house, they would say, “Yeah, that’s some kind of shelter”. They would get it. So it really depends on how you apply it – language is pretty arbitrary, whereas imagery is not arbitrary…”

I thought that this was fascinating, because as a photographer who came of age and studied in the late-twentieth century (and has made work primarily within the twenty-first century), I was always told that it was the image that was the most ambiguous, malleable and the arbitrary of all mediums, whereas language was something much more exact and precise. With this in mind, I asked him, “So what makes you choose to use an arbitrary medium rather than an unarbitrary one, or vice versa – why use a photograph of a house in one instance, and the word in another?” And his response was brilliant – almost as if a contemporary Dickinson were asked today why she used slant rhyme: “Really, I’m just interested in fucking people up when they’re looking at my work. I think the artist should make things difficult for the viewer”.

FC: Truth, at times, is stranger than fiction, as they say, and the media offer a very fertile soil where one can gather multiple cabinets of absurdities. The art of collecting weird/surreal news has been practiced by a number of artists internationally, including, among others, the recently deceased Lorenzo Tricoli with his project, The Archive You Deserve, on the tragicomic history of Italian politics and folklore. Do you think there is a specific ‘American surreality’ in the news of the local press? Could you guide a bit the non-American reader through the labyrinth of your selection for SLANT?

AS: What I love about these particular ‘Police Reports’ is that, at least within their tone and in this particular context of a local paper, they are in no way meant to be intentionally weird or funny. There’s a long history of newspapers, magazine and websites publishing ‘Weird News’ – crazy stories of unlikely events, meant to tickle the reader. But it’s my understanding that, in this very local, weekly newspaper, these reports are simply there to inform those in the community of what is going on around town when it comes to the police.

That said, what the nature of the ‘Police Reports’ does imply – and I think that this is true particularly in America, but not exclusively of course – is that the news, even when presented in the straightest, most objective manner in the context of a small-town newspaper, is often something not only informative, but also slightly salacious and unnerving, if not shocking. The news in America is often delivered in an incredibly amplified, exaggerated and sensational manner – as a form of entertainment, rather than as a means to inform the public; if one takes it at face value, it’s as if we’re all living in an apocalyptic horror movie or an episode of CSI all the time.

The fact is that Amherst – along with its surrounding area – is an incredibly safe, mild-mannered and peaceful place, certainly in comparison with the other parts of America, let alone the rest of the world. Of course terrible things very occasionally happen there, as they do everywhere, but for the most part it really doesn’t have much going on in the way of violence, crime or imminent threat. Nevertheless, as the ‘Police Reports’ reveal, this doesn’t necessarily mean that there isn’t an underlying sense of insecurity or impending doom. As a matter of fact, in many cases it seems that the general peacefulness of the place only serves to heighten a certain sense of insecurity and paranoia, hence so many unsubstantiated and imagined reports of ‘unlocated’ peeping-Toms, potential intruders, lurking criminals, strange noises, suspicious ‘foreign’ accents and so on. It’s as if, having been exposed via the media to so many crime-procedurals, spy dramas, action thrillers, horror movies, and overtly-sensationalised news stories, many people in Amherst (and America) now feel as if they’re actually living in one themselves, even if they’re simply sleeping in their own bed on a silent night in a small town.

Furthermore, alongside the rise of Trump over the last two years, his persistent questioning of the mainstream press and its legitimacy, and the introduction of terms such as ‘fake news’, ‘alternative facts’ and ‘post-truth’ into the popular consciousness, notions of how to define ‘truth’, and what it might be, has become increasingly blurred and confused in America, particularly when it comes to journalism. Truth is no longer stranger than fiction, but is instead considered a kind of fiction; and reversely, fiction is now considered a kind of truth. Initially, in 2014, I simply found these newspaper ‘Police Reports’ quaint and hilarious. But today, in 2017, I actually find them both unexpectedly poignant and painfully disturbing; they seem to reveal certain worrying undercurrents in America, psychological or otherwise, that point to a particular loss, at least in terms of being in touch with reality.

Also, on a different note, the rise of things such as ‘fake news’ and Trump’s ‘alternative facts’ obviously puts an entirely different and slightly sinister spin on the title and first line of Dickinson’s poem – ‘Tell all the truth but tell it slant…’

[1] “I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor, and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and offbeat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and beyond and above these figs were many more figs I couldn’t quite make out. I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet”. Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar, 1963

[2] Hilde Van Gelder and Helen Westgeest, Photography Theory in Historical Perspective, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, 2011, p. 165

Aaron Schuman is an artist, writer, editor and curator based in the United Kingdom. His photographic work is exhibited and published internationally, and is held in a number of public and private collections. Schuman is the author of FALLING (NB Books, 2017) and FOLK (NB Books, 2016), and has contributed texts to a number of recent books including George Rodger: Nuba & Latuka—The Colour Photographs (Prestel, 2017), Alec Soth: Gathered Leaves (MACK, 2015), Vision Anew (University of California Press, 2015), The Photographer’s Playbook (Aperture, 2014), and Pieter Hugo: This Must Be the Place (Prestel, 2012), amongst many others; he also regularly writes for magazines such as Aperture, Foam, Frieze, TIME, Hotshoe, The British Journal of Photography and more. Additionally, Schuman has curated several major exhibitions, including Indivisible: New American Documents (FOMU Antwerp, 2016), In Appropriation (Houston Center of Photography, 2012), Other I: Alec Soth, WassinkLundgren, Viviane Sassen (Hotshoe London, 2011), and Whatever Was Splendid: New American Photographs (FotoFest, 2010). In 2014, Schuman served as Chief Curator of Krakow Photomonth 2014 – entitled Re:Search, the main programme featured exhibitions by Taryn Simon, Trevor Paglen, David Campany, Clare Strand, Jason Fulford and more. Schuman is the founder and editor of SeeSaw Magazine (2004-2014, seesawmagazine.com), a Senior Lecturer in Photography at the University of Brighton, and Course Leader of MA Photography at the University of the West of England (UWE), Bristol. He is the guest curator for Jaipur Photo 2018.

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist

Aaron Schuman, from the series SLANT, 2017, courtesy the artist